To find a person whose life embodies the major milestones of a century is rare. But to one Fordham historian, Ralph Bunche, the first African-American Nobel Peace Prize winner, comes remarkably close.

Photo by Chaewon Seo

Christopher Dietrich, Ph.D., an assistant professor of history at Fordham, is at work on a biography of Bunche. It’s not the first, but he hopes it will bring to the fore new ideas about 20th-century politics, society, and foreign relations. Dietrich is one of five scholars nationwide to receive the 2016 Nancy Weiss Malkiel Junior Faculty Fellowship from the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, which he will use to do research toward the book, titled Tortured Peace: Ralph Bunche, Race, and UN Peacemaking.

“Ralph Bunche hated being identified as the first person of color to do things, but he was a trailblazer,” said Dietrich.

Bunche’s life as a scholar, diplomat, peacemaker, rights activist, and intellectual spanned the critical decades of the 20th century—from the 1920s to the 1970s. It was a time, said Dietrich, when tumult both at home and abroad ran high, and Bunche came to be at the center of new ideas about race and oppression as “probably the most well-known black person in the world after having won the Nobel Peace Prize.”

The Talented Tenth

Bunche had early aspirations to be one of W.E.B. Du Bois’ Talented Tenth, Dietrich said, a group of elite African-American scholars who could serve as thought leaders for their race. Following his graduation from UCLA in 1927 (he was valedictorian of his class), Bunche went to Harvard and became the first African American to earn a doctorate of political science from an American university.

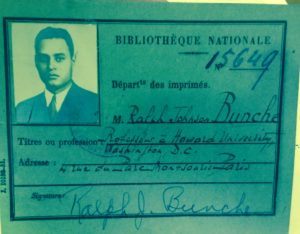

Photo by Chris Dietrich

Dietrich’s initial interest in Bunche arose from reading the scholar’s Harvard dissertation on African colonialism and the mandate system at the League of Nations. Bunche had done fieldwork research in French West Africa, and his analysis of colonialism, global oppression, and political systems was “strikingly radical” for its time, he said.

“His dissertation sits somewhere in between Lenin and the West in its critique of colonialism as an oppressive capitalist system,” said Dietrich. “He believed strongly in independence from colonial rule.”

At the same time, says Dietrich, Bunche’s overview in the 1930s was shaped by his radical belief that class trumps race in the fight to overcome oppression. “He believed in order for there to be a change in the political system, the white working class and black working class needed to form a coalition,” and that, globally, those under colonial rule no matter the race—Africans, Asians, Middle Easterners, Indians, and others—all shared a similar “self-aware spirit of hopefulness” that they’d be able to conquer racist systems.

“This is an African-American man saying this—someone who assigns Marxist economic tracts to his students,” said Dietrich. “It was radical.”

Bunche and the U.N.

Enter World War II. Already a well-respected Howard University professor, Bunche was summoned by the Roosevelt Administration to work in the Department of State, said Dietrich, as one of the nation’s leading experts on African-continent colonialism. He then became involved in the planning for the United Nations (to replace the League of Nations), and was instrumental in writing certain articles in the U.N. charter.

“Bunche presses for, and in fact partially authors, clauses in the charter that allow colonized peoples to make direct reports and demands [for ending colonial rule] of the U.N.,” he said.

Such work, he said, had a “quickening effect” on the process of decolonization around the world. From the U.N.’s founding in 1948 into the end of the 1970s, the member nations grew from the original 51 to more than 150—many of them African, Asian, or Middle Eastern former colonies that arrived at independence.

Nobel Undertakings and Civil Rights

As the visibility of race and globalism advanced, Bunche’s expertise was in high demand, said Dietrich. As the director and key player in the U.N. Observer Group in Palestine, he became the lead negotiator in the 1948 Arab-Israeli conflict, implementing first a cease-fire and then the armistice agreement. For his peacekeeping role, he was awarded the 1950 Nobel prize.

When the Civil Rights movement came into its own in the second half of the 20th century, Bunche was a solid supporter, yet grew “deeply critical of the more radical side” of the movement, said Dietrich, due to his strong commitment to peacemaking. He locked arms with Martin Luther King Jr. in the Selma march and marched on Washington in 1963. But he grew disillusioned with certain activist and separatist factions and their leaders, including Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael.

“Carmichael famously said ‘You can’t have Bunche for lunch,’” said Dietrich—the suggestion being he was considered a lightweight by radical black activists.

Dietrich said Bunche continued working at the U.N., negotiating peace efforts in the Congo and being an outspoken critic against the Vietnam War, until his death in 1971.

“Bunche’s life was very particular to the mid-20th century and the major challenges facing the nation and world—whether it was civil rights at home or decolonization abroad,” said Dietrich. “Through his biography, we have a chance to see how somebody with a penetrating intellect and forceful presence navigated the great moments of his day when universal questions come into play—the tension between idealism and pragmatism, the work necessary to find justice and peace. These are some questions that are forever relevant to the human condition.”