Lead contamination in drinking water made headlines because of the crisis in Flint, Mich., and now reports show children’s health is being threatened nationwide.

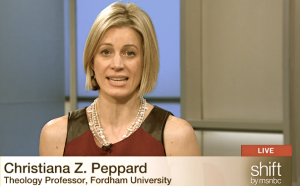

Fordham’s resident “water ethics” expert, Christiana Peppard, PhD, assistant professor of theology, science and ethics, shared the following thoughts on the situation:

**

Until recently, people in the U.S. have tended to think that “water crises” happen to other people in other parts of the world, that “water security” is an issue for global diplomacy more than our own faucets.

But now, the invisible is becoming visible with regard to United States water: across this vast country there are water problems, from California’s drought to the effects of agricultural runoff on Toledo’s drinking water. The public health disaster and environmental racism evident in Flint’s contaminated water supply has extended to Newark Schools. And now a USAToday piece reveals levels of lead far beyond the regulatory standard in more than 2,000 locations.

This is serious.

Lead contamination from old pipes and other forms of chemical leaching is a known issue to water infrastructure experts: Many municipalities take major steps to ensure that drinking water leaving their treatment plants meets federal standards.

Obviously, that failed in Flint. But apart from violations of municipal water supply (as in Flint), lead can enter water supply at points of entry to schools, homes, and other buildings. This is the case for many of the sites profiled by the USAToday team.

Given the deleterious impacts of lead on children’s brain development, and the negative health effects across the lifespan of lead and other undesirable compounds in water, what should you do?

There are six steps: (1) get your water tested, (2) learn about your municipal water quality and treatment, (3) consider an under-sink water filter, (4) regard bottled water as a stop-gap measure for public health emergencies, not a long-term solution, (5) learn about your watershed, and (6) figure out what you can contribute to developing consciousness about water ethics. Water is all of our responsibility, on many levels of scale.

Let me assure you that you don’t have to be a water expert to do any of this. Even if you’re terrified (and frankly, often I am too!), take a deep breath, and jump in—because in fact, simply by being connected to water sources, you are already immersed in these issues. And we can do better.

- Get Your Water Tested at Home

Get your water tested at the faucet(s) in your home. This will tell you about what is in the water that you drink and use for bathing and other domestic purposes. This is the data you will use in deciding what kinds of filtration and purification systems to choose (see #3). If you live in a building built in or before the 1950s, you must do this. But really, everyone should do this.

- Get Water Quality Data from your Municipality and/or Water Provider.

Get data about municipal water quality from your water provider. Compare this to the data about your household water (#1). This is how you will see what undesirables are entering your water through your own home pipes (beyond the municipal infrastructure).

In other words, data from your water provider gives you bigger-picture information that you can use. By comparing the municipal data to your own faucet data, you can see whether and how your home’s water quality differs from that of the local water provider. This will help you select a filtration or purification method (see #3).

And by paying attention to the water quality report from the water provider, you get a sense of the “terroir” of your water. (Yes, just like wine, water has a local and regional “terroir”—it takes the shape, taste, and influences of the land and environments through which it passes!*)

Finally, I recommend you get information about how your water provider treats that water before piping it to your house. There are many effective methods of water treatment at the municipal level (and some accessible books about treatment of water from past to present, like Water 4.0 by David Sedlak.

- Invest in a Water Filter that Connects to your Water Supply.

There are many types of water filters and filtration or purification systems. Many people recommend under-sink or whole-house water filters (the latter works better for people in freestanding residences, obviously, than in does for people living in apartments). The best systems take out heavy metals (mercury, lead) as well as organic compounds, agricultural products like herbicides and pesticides, and some pharmaceuticals.

The most powerful kind of water treatment is reverse osmosis (RO), which basically removes everything from the water (including minerals that make water taste good). Some products now offer RO filters that retain the minerals in tap water or even re-mineralize the water after it’s been filtered. (Reverse osmosis with re-mineralization, among other treatments, is what companies like Coca-Cola and Pepsi use to treat the tap water that becomes Dasani and Aquafina. In other words, they take everything out, then add proprietary mineral compounds back in to make the water taste better!)

Most counter-top filters do not filter out lead. If your water has lead problems and you’re not going to do an under-sink filter installation, please make sure you get one that filters lead (and mercury and arsenic and other undesirables).

- Bottled water is a stopgap measure; it is not a long-term solution.

The convenience of bottled water is undeniable. In cases of public health emergencies, it is ethically justifiable to use bottled water. So if you are freaking out about known levels of lead in your water, or you have to wait to get your water tested, then there is an argument for drinking bottled water in the very short-term because you are seeking wellness and avoiding a public health crisis. But bottled water is not a long-term solution. It is convenient; in public health crises it is important; but it is a bandage for an issue that needs a very different kind of treatment.

(I and other water experts have written elsewhere about bottled water as an ethical issue, especially in industrialized nations with the capacity to invest in and maintain reliable water infrastructure.)**

- Learn about your Watershed, and Figure Out Where to Jump in to Local Conversations about Water.

Water is constantly in motion, and while it is a universal human need, the “terroir” and sources of your water are particular to the place where you live. So learn about your watershed! And then, advocate for and get involved in making sure that many civic energies, public monies, and initiatives are oriented towards water infrastructure updates—not just repairs.

Our human bodies of water rely upon broader bodies of water. We can protect, maintain, and provide water in better and worse ways. It requires a bit of foresight, and a lot of persistence, to keep water in our sight lines. But isn’t that important, for something that undergirds all of our wellbeing and makes our lives possible?

- Delve into Water Ethics

How societies interact with water is a major ethical question, not just a political one. For example, what does it mean to distribute water ethically? What does it mean to be virtuous with regard to water? Who is entitled to water? Who should provide it? Is water best viewed as a gift of nature, an economic commodity, a human right? These topics are part of an emerging discourse on “water ethics.”

Trust me: You don’t have to be a water expert to engage in water ethics—you just have to be someone who breathes, cares, lives in a watershed. All of us can begin to think and act well about water. Let’s be those people, for ourselves and for others.

I invite you to join this conversation, by:

- watching “The Importance of a Water Ethic,” a video produced by the Center for Humans and Nature for World Water Day 2016.

- reading one book: Blue Revolution: Unmaking America’s Water Crisis, by Cynthia Barnett (http://www.beacon.org/Blue-Revolution-P945.aspx)

—

Christiana Z. Peppard, Ph.D. (@profpeppard) is the author of Just Water: Theology, Ethics, and the Global Water Crisis (2014) and an expert on water, ethics, and religion and science. She has written for and appeared in public media venues such as The New Republic, Public Radio International, The Washingon Post, TED-Ed, MSNBC, and CNN.com.