Drumming, of all things, turned out the be a savior of sorts for Benedict Carrizzo, FCRH ’18.

“The only place I didn’t feel like an awkward weirdo was on those drums,” Carrizzo said.

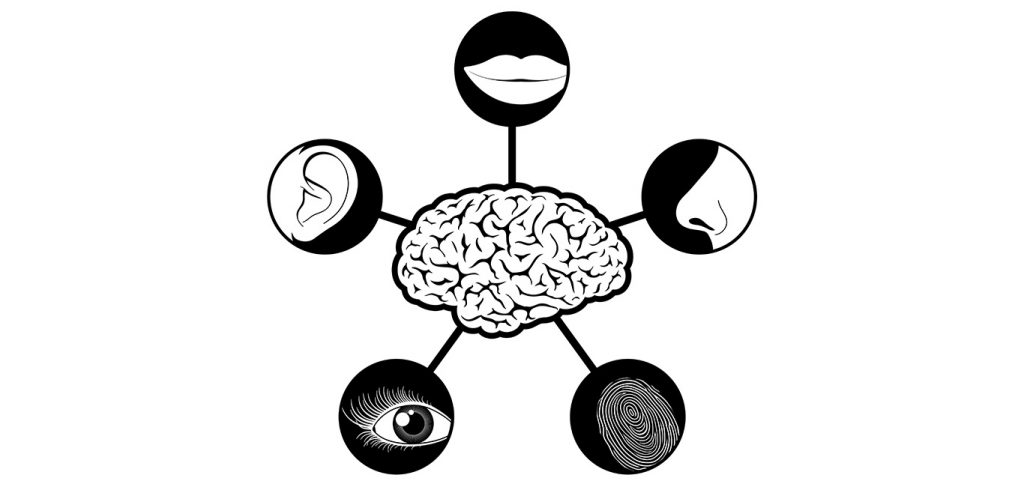

The reason for his discomfort in otherwise normal situations was sensory processing disorder (SPD), a neurological condition that’s characterized by difficulties in processing sensory information. For people who suffer from SPD, their sense of smell, taste, sound, sight, and touch is, for lack of a better term, out of whack.

For Carrizzo, who graduated on May 19 from Fordham College at Rose Hill with a degree in communications, that meant a reclusive childhood. Milk a cow with other children on a field trip to a farm? No way, the feel of an utter freaked him out. Gaze upon a train as it whizzed by the playground? Not an option; the noise hurt his ears. Even though he loved to play with toy trains, the sight of a real one left him trembling in fear. Even his sense of balance was affected.

“When I was little, I was the most cautious kid you could imagine. I never had a sense of where I was at a particular moment. Even on a small ledge, I’d be so careful and concise about where I was going,” he said.

With his parents’ help, Carrizzo learned how to manage most of the symptoms he endured as a child, and he recently used his experience as the basis of his radio project Hidden in Plain Sight: Sensory Processing Disorder. The 24-minute-long documentary was featured on WFUV, Fordham’s public media station, where he worked from his sophomore to senior years.

“I grew up with this condition nobody knows about, and it affected my life greatly, so I thought it would be good idea to shed light on it,” he said.

The documentary took several months, and in addition to talking about his own experiences, he interviewed experts such as those from the STAR institute for Sensory Processing Disorder, a treatment, research, and education center for children and adults with SPD, and Temple Grandin, Ph.D., a professor at Colorado State University. Grandin was lauded in Time magazine’s 2010 annual list of the 100 most influential people in the world for her work with people who are on the autism spectrum.

When Grandin, who has SPD, was little, she said, she thought adults had their own language, because she was only hearing vowel sounds. One of the things she recommends in the documentary is to use headsets for alleviating the pain someone with SPD might encounter in public restrooms, where loud, unpredictable noises from hand dryers are found.

In the feature, Carrizzo addressed the ongoing effort to have SPD listed in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Presently, the association only lists it as a symptom of autism.

He also tried to help listeners understand what it’s like to be feel pain when exposed to everyday sights and sensations. To get across the feeling of being irritated by the buzzing of fluorescent lights, Carrizzo convinced a security guard to let him into the Rose Hill Gym at 1 a.m., where he fastened a recorder to a pole and held it close to a ceiling light.

To cope with such challenges, he developed several strategies as a child. Singing and talking to himself while on swings helped him develop “laser-like focus,” as his mother put it in an interview for the documentary, and playing drums desensitized him to loud sounds.

Carrizzo hopes his own experience can provide hope and advice for parents whose children are experiencing SPD, he said.

“It’s crucial for parents to make sure their children with sensory issues don’t stay in their room all day. To get ‘in sync,’ they need to be exposed to the outside world. They need a ‘sensory diet’ to get them on track,” Carrizzo said.

Today, he said, transcendental meditation helps him enormously. Sound and touch are no longer as challenging for him, but he said he does still have issues with his vestibulur senses, which are tied to balance, and his proprioceptive senses, which give us body awareness. It made for a challenge when he was asked, at an internship at Fox News, to interview people on the street, and he inadvertently got uncomfortably close them. Just being cognizant of this tendency helps him.

“The majority of my symptoms have diminished, but I still have some lingering problems, so I try my best to avoid what gets me ‘out of sync’ so I can live as productively as possible,” he said.

“The best thing for someone with SPD to do is to know themselves.”