On Thursday, Nov. 4, at 6 p.m., the movement will be the focus of a technological expansion of Fordham’s own Center on Religion and Culture, which will premiere its first documentary short film The Shaker Legacy at a screening at Lincoln Center’s Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center. (Password: FORDHAM) The film focuses on the connection between the group’s deeply held religious beliefs and Shaker furniture, for which they are well known.

The screening of the nine-minute film will be followed by a panel discussion featuring two experts from the film, Kathryn Reklis, Ph.D., an associate professor of theology at Fordham, and Lacy Schutz, executive director of the Shaker Museum and the historic Shaker site in New Lebanon, New York.

The panel will also feature Courtney Bender, Ph.D., a professor of religion at Columbia University. It will be moderated by Center on Religion and Culture Director David Gibson, who led the project and narrated the film.

Gibson said filmmaking was something he’d hoped to do since joining Fordham in 2017, and the work that Reklis had done on the Shakers with a Luce Grant she secured in 2018 struck him as the perfect opportunity.

“We want to highlight Fordham’s faculty and research efforts, and we also want to ground this in religion, culture, and New York,” he said.

“So this whole project about the Shakers, and the new museum they’re building in Chatham, New York, is perfect for this kind of treatment.”

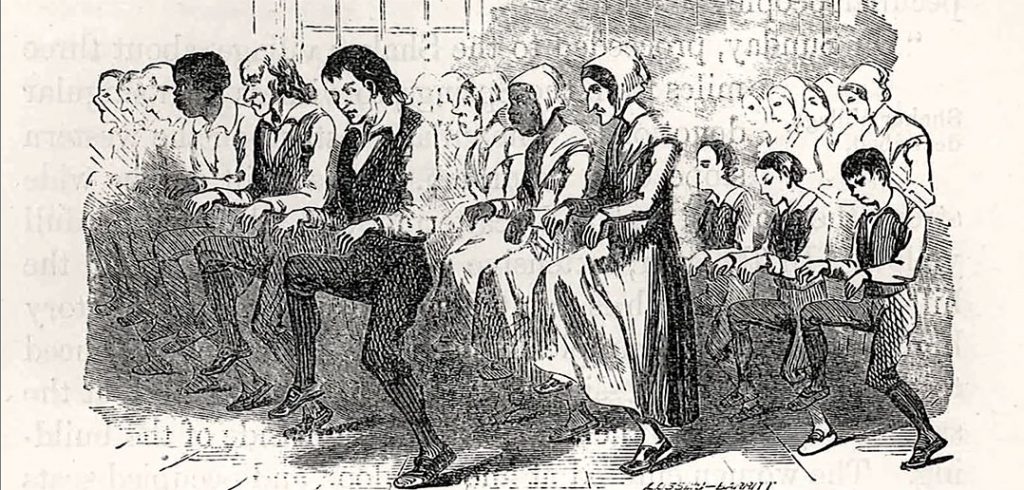

The film, which is a mix of archival photography, drone footage, and on-site interviews with Reklis and Schutz, is meant to whet the appetite of those who know nothing of the Shakers. The group was founded in 1770 by Mother Ann Lee, a native of England who moved to the United States in 1774 and eventually settled near Albany. The group she founded was defined by a radical embrace of celibacy; communal living; simple, elegant furniture; and ecstatic behavior during worship services that earned the group the “Shaker” name.

For Reklis, the Shakers offer an opportunity to reflect on what it means to be an American, what it means to be religious, and what it means to live in a community. These are questions that have resonated even more since the start of the pandemic, she said. Many of the experts she convened as part of her research project told her they were first drawn to Shaker furniture, whose influence can be seen today in every Ikea around the world. But as these scholars learned more about the Shakers, they quickly concluded that the furniture was simply a physical manifestation of a deeper, radical take on life.

“Our fixation became about questions of utopianism and community. Is it possible to think outside of capitalist models of production, communal arrangements, and taking care of each other?” she said.

“None of us are going to become Shakers, take vows of celibacy, or live in this communal life. But why are they so perennially fascinating, and what can we learn about the kind of radical visions they had about what it meant to be religious, American, and a witness to something really distinct?”

Viewed from today’s perspective, the Shakers were profoundly paradoxical, she said. Since all members took a vow of celibacy, no one was born into the group, which lasted 150 years (there are currently three members left). All new members were either converted or were taken in as orphans, as there were no state-run orphanages in the United States at the time. That necessitated an openness to outsiders, who brought with them new skills and expertise. It also resulted in communities where men and women were treated equally, and Black and white converts were welcome.

“They embraced every technology that came along. Many of the communities had 400, 500, or 600 people living together. To produce the food that you needed, you needed to embrace mass scale,” she noted.

“What I find most intriguing about the Shakers is where their unique theology and ecstatic religious experience met really practical, communal life concerns. That’s super fascinating to me, and I hope that other people will be intrigued and maybe think for a moment about different models.”

Gibson said he hoped that focusing on the design legacy of the Shakers would spur viewers to explore the Shakers in a more depth way.

“We wanted to highlight not what a cool Shaker box looks like, or a Shaker-style chair. People know that. We really wanted to focus on where that design came from. It’s not just a look or an aesthetic. It was born out of their religious beliefs and their communal style of living. It was very practical; it was very pragmatic,” he said.

“This was the largest Utopian movement in U.S. history, and it lasted 150 years. It’s another part of our country’s history, and even as we’re being torn apart now, there’s another path that we have followed in the past and that we can learn from today.”