For Sophia Maier, a senior at Fordham College at Rose Hill, interest in Bronx Jewish history was sparked when she interviewed her grandparents about their upbringing for a Bronx history course at Fordham.

“I said, ‘all right, well this is really important,’” she said. “So I did my thesis on doing oral history interviews with folks who grew up in the Bronx and left during the period of white flight in the 60s and 70s and into the 80s.”

She added that her research, which included interviews with more than 40 community member so far, focused mainly “on the 40s, 50s, and into the early 60s—a lot of those folks are people whose grandparents immigrated to this country, typically from Eastern Europe.”

“Since they came into this country, there has been this sort of upward movement—both geographically and on a class basis, starting out on the Lower East Side, or Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in this kind of crowded tenement living, [and then]folks moved up to the South Bronx, or then further up into the Northwest Bronx.”

Maier and Reyna Stovall, a sophomore at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, shared their research on March 1 at “Jews in the Bronx: Archival and Oral Histories,” an event hosted by Center for Jewish Studies. They were joined by Daniel Soyer, Ph.D., professor of history; Ayala Fader, professor of anthropology; and Ayelet Brinn, Ph.D., the Philip D. Feltman assistant professor of modern Jewish history at the University of Hartford who did postdoctoral research at Fordham.

The students’ work is at the heart of a new initiative of the Center—the Bronx Jewish History Project, which was publicly launched at the event. Maier’s interviews, paired with Stovall’s archival research, are the basis for the project, Sarit Kattan Gribetz, Ph.D., associate professor in the theology department, said. It was also partially inspired by the Bronx African American History Project, which was founded by Mark Naison, Ph.D., professor of African and African American studies.

Magda Teter, Shvidler Chair of Judaic Studies and co-director of the Center for Jewish Studies, helped introduce and combine the students’ work into a larger project that will live beyond their time at Fordham, Gribetz said.

“Through our new initiatives at the Center for Jewish Studies, we’re collaborating across generations and fields to collect, preserve, share, and learn from these stories,” Gribetz said.

Piecing Together History

Stovall came to Fordham from San Antonio, Texas, and didn’t have any connection to the Bronx. Working for the Holocaust Museum in Texas piqued her interest in Jewish Studies though, so she minored in it at Fordham, and met Teter.

“I met Dr. Teter, who said, “Oh, we just got these new interesting documents from the Jewish Bronx, and I thought, ‘The Jewish Bronx? I thought the Jews lived in Brooklyn,’” Stovall, who is Jewish, said with a laugh. “I wasn’t aware of the significance of the Bronx to Jewish history.”

She began interning with the center last semester and began “deep diving into all of these archives that we started acquiring.” In the spring of 2020, the center hosted a virtual event called “Remnants: Photographs of the Jewish Bronx.”

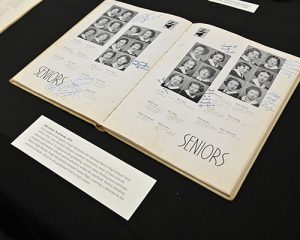

Ellen Meshnick Immerman, who grew up in New York, attended, and was so inspired by the event that she donated material, including everything from yearbooks to bar mitzvah invitations from her parents, Frank and Martha Meshnick, who had grown up in the Bronx.

“Looking at them was absolutely fascinating to me—getting to know people’s stories through the little bits and pieces of their lives,” Stovall said.

The Meshnick’s documents “really opened my eyes to how special the Bronx is,” she said.

Stovall also spoke with Meshnick Immerman, and the conversation elevated the work to a new level, she said.

“I had this vision of what their life was like in my head, but getting to talk to her, I got to know more the feelings that were associated with it—how her mother put so much pride in her appearance, how they went to these stores to prepare for these certain things for their Shabbat days, just things like that that showed me the dimensions of history.”

Capturing Untold Stories

Maier’s project started with interviews with her grandparents, and is rooted in oral histories. She’s conducted more than 40 interviews so far, with “more coming everyday,” including one scheduled in a few days with a Bronx resident who survived the Holocaust.

She found that Jewish people, particularly those in the South Bronx through the 40s, 50s, and 60s, lived in “really diverse neighborhoods and environments” where they felt “secure” and like they were a part of a larger community.

“People were like, ‘Oh, I never locked my door,’ or ‘My Italian neighbor across the street, she’d always give me cookies when I came home,’—things like that, that kind of captures the sentiments of how people were feeling,” she said.

Residents described how schools were integrated, although there were tactics employed to keep many of the white students in classrooms separate from the Black students. But many said their diverse, public education was at the heart of the upward mobility they were able to achieve.

“For a lot of the people that I spoke to, their parents were kind of manual laborers, truck drivers, small business owners, factory workers. But because of the great public education that they got and continued for college education, a lot of them were teachers and doctors of various kinds.”

Many Jewish people left the Bronx, Maier said, as a part of their “striving toward this solid middle class standard of life,” which included wanting more space for their families and being able to afford the suburbs. But interviewees also told her their families left because “the Bronx was changing.’ At that time, many Black and Hispanic residents were moving into the Bronx, and many Jews people moved out.

“Leaving the Bronx for a lot of Jews, meant leaving this distinctly Jewish place—you didn’t have to be a religious Jew to be a Jew in the Bronx,” she said.

Tying the Stories to the Artifacts

Stovall said that she believes this marriage of archival material with oral histories is what makes the Bronx Jewish History Project so unique.

“I get to see both sides of history—the emotions and feelings that are associated with the Bronx, but also the archival materials,” Stovall said, adding that the project will carry a record of their history forward.

Learn more about the Bronx Jewish History project and other initiatives taking place at the Center for Jewish Studies.