The book, Feminism’s Forgotten Fight: The Unfinished Struggle for Work and Family (Harvard University Press, 2018), argues that second-wave feminists did not fail to deliver on their promises; rather, a conformist society pushed back against far-reaching changes sought by these activists. The book’s arc begins with the intimate sphere of the family in the 1950s and then moves on to larger societal changes where two-income families became the unavoidable economic norm.

The book, Feminism’s Forgotten Fight: The Unfinished Struggle for Work and Family (Harvard University Press, 2018), argues that second-wave feminists did not fail to deliver on their promises; rather, a conformist society pushed back against far-reaching changes sought by these activists. The book’s arc begins with the intimate sphere of the family in the 1950s and then moves on to larger societal changes where two-income families became the unavoidable economic norm.

“My focus is on the story of a broad feminist vision that wasn’t fully realized,” said Swinth. “There were a lot of gains generally, but the movement also generated an antifeminist backlash so that most of the aspirations, like a sane and sustainable balance for work and family, were defeated.”

Swinth said the movement was affected by a brand of far-right conservatism that would take hold in the Reagan administration but actually began in the early 1970s in the Nixon administration.

“Their opposition undercut feminism’s most far reaching aspirations, many of which are so urgently needed today, so it was a missed opportunity,” said Swinth.

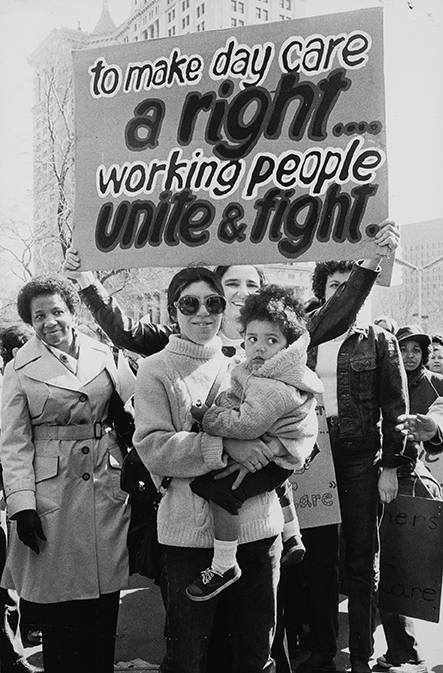

President Nixon initially supported the Comprehensive Child Development Act that would have provided universal child care, she said. But conservatives, like Pat Buchanan, advised Nixon to withhold support, equating it to communist childcare. Swinth said the defeat was the “very early inkling of the conservative right” that would go on to elect Ronald Reagan and now runs the Republican Party.

“Working women were deeply threatening to the established norms of male patriarchy,” said Swinth.

But feminists were simply facing the economic reality of both parents needing to work, which would mean that children would need care outside of the home, said Swinth. Feminists just wanted what was “normal and fair” and called out what they saw as “unfair and unjust,” shifting the national culture in the process.

Swinth said much of the groundwork had been laid by African-American and Latina feminists in the welfare rights and guaranteed income movements.

“They understood that all mothers should be able to take care of their children, so they fought to change the discussion of welfare to one that recognized the value of women’s labor to society,” said Swinth. “Plus, there was and is a social stake in raising families.”

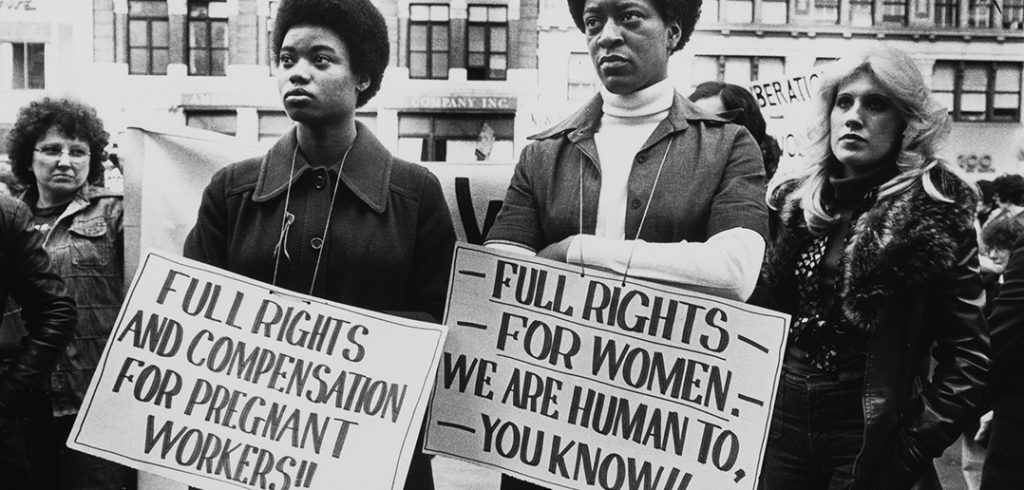

Swinth said the idea that second wave feminism was a “white feminism” is a distortion of the historical record.

“African-American women and Latinas were self-identified feminists who negotiated a distinct position through nationalism rights, civil rights, and their own developing feminism,” she said. “Women of color had some of the most vanguard, pioneering ideas. When we declare 1960s and ’70s as white feminism, we delegitimize the claims they have on the feminist movement. They made a set of pioneering arguments for support of poor mothers by advocating for jobs that were compatible with caring for the kids.”

Swinth said that while today people talk about work and family balance, this certainly wasn’t the case in the era before the 1960s, when the family’s care was the mother’s realm. As such, the feminist cause had to go beyond policy and toward perceptions, she said.

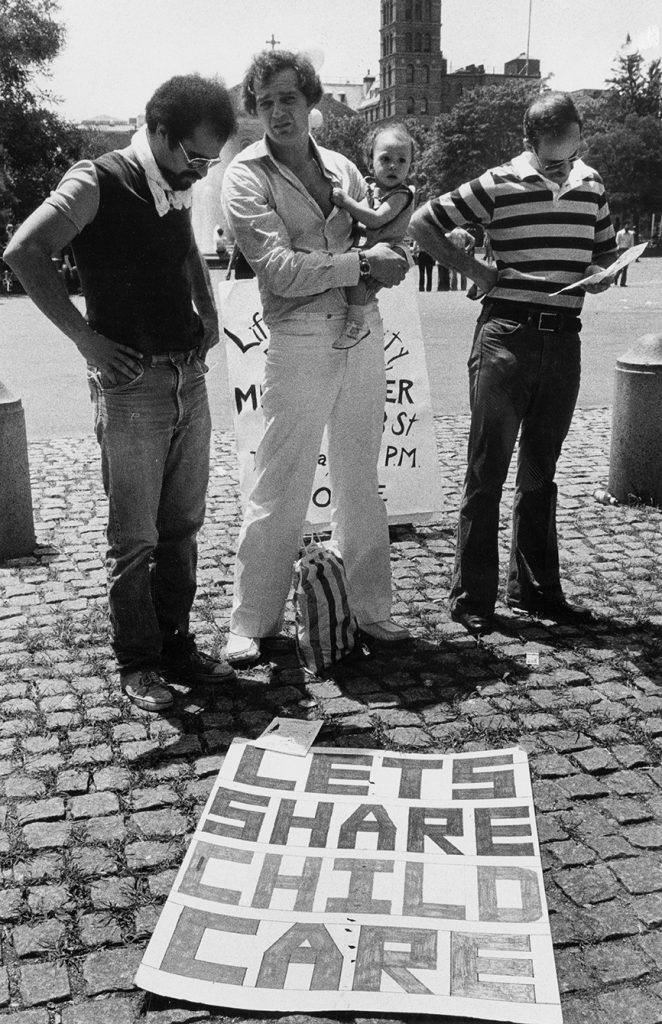

“Feminists struggled to create shared labor with men through caretaking and changing men’s roles, and the very meaning of fatherhood,” she said.

Swinth said that she also researched several male feminists who, she said, understood that being “involved fathers was good for men, for the kids, and good for equality.”

Much of the book focuses on issues outside of the home, from grassroots organizing to a chapter detailing Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s fight to end pregnancy discrimination. As an assistant adjunct law professor at Rutgers University in the 1960s, Ginsberg hid her pregnancy out of fear she’d lose her job. Later, as a tenured professor at Columbia University, she helped draft the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, which made it illegal to discriminate against pregnant women in the workplace.

“Employers could fire someone who became pregnant or drop her insurance because the man would support her. Why would you need to make any accommodations for a worker to leave?” Swinth asked rhetorically.

But by the late 1970s, women’s earning power had become essential, she said, forcing many to acknowledge the reality that women weren’t about to “step out of the wager force.” Swinth noted that while many feminists were indeed “radical socialists” with visions of 24-hour child care, local activists negotiated more realistic after-school child care at local libraries. Local activism in turn spawned women leaders in city government, which eventually led to representation at the state and federal levels.

“It’s absolutely critical history for us to have as women so we can continue to fight with a new energy and a set of lessons that we need to inspire us,” Swinth said of the book. “There’s a past here where we can recognize ourselves and our needs. We should continue to be inspired by the determinations and creativity of these women—and men—from our past.”