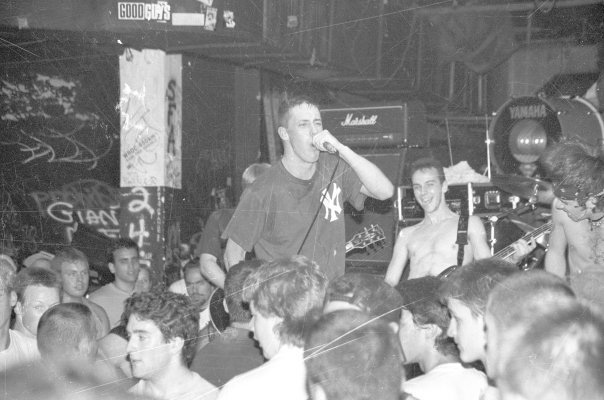

Murphy greets a concertgoer with the easy self-confidence of someone uninterested in looking or playing the part of the ego-driven lead singer. That stereotype is one of several that don’t apply to Murphy, who retired from a successful career in finance at the end of 2011 to re-pursue his main passion, music, nearly 25 years after he played CBGB as a Fordham student.

In conversation, his candor reflects the humble urgency that imbues punk ideology: to remain true to one’s ideals while maintaining a social consciousness. Going against the grain isn’t a passing fancy, and for the musicians in Kings Destroy, it means playing from the heart, not watering down your message.

Weaving New York’s underground hardcore and graffiti movements of the mid-’80s, hedge fund management, philanthropy, all things Fordham, and Brooklyn’s current affinity for heavy metal music into one seamless conversation may sound preposterous—unless of course you’re speaking with Murphy.

From Rose Hill to CBGB

Born in the Bronx like his parents and grandparents before him, Murphy is the oldest of eight children. He attended a Jesuit high school in Rochester, New York, and was admitted to Fordham last minute, he says, after a mishap with a recommendation letter initially resulted in a rejection. Just five days away from leaving for Loyola University Chicago, he received an acceptance letter from Fordham, including a generous financial aid package that afforded him the opportunity to attend his first-choice school.

He thrived academically, majoring in political science and economics, and found a close-knit community in New York’s underground graffiti and hardcore scene. It was rife with artistic integrity fueled by rage against socioeconomic injustice, he says, but burning with a purity that connected races, religions, and nationalities to create a community of artists and activists.

Although punk is stereotypically associated with mohawks, piercings, and spiked accessories, for some, underground band T-shirts serve as a beacon to like-minded people. The latter is how Murphy met two of his bandmates—guitarist Carl Porcaro, GABELLI ’89, and drummer Rob Sefcik, FCRH ’87—on the Rose Hill campus.

“We would see each other in the distance wearing T-shirts of very obscure punk rock bands that nobody else would know,” Murphy explains. He also played rugby at Fordham, so he straddled the line between the “punk” world and the “jock” scene, although he doesn’t like to refer to it in those terms because, to him, it was normal to walk that line.

“I used to wear a jean jacket that had Black Flag bleached on the back, and Rob said he and his circle of friends used to make fun of me because they thought I was a poseur,” Murphy recalls with a laugh. “But we eventually became friends and went to shows together all the time.”

A Diverse Downtown Arts Scene

In 1987, Murphy and Sefcik played in their first band together, the hardcore outfit Uppercut, with another Fordham guy named Pat Trainor, FCRH ’90. “They asked me to audition as a singer for their band. I was the third singer to try out and got the job immediately,” Murphy recalls.

“Carl started his own band, Breakdown, with non-Fordham people,” he continues. “He was from Yonkers and he was a commuter, so he wasn’t around that much, whereas Rob and I lived on campus. Carl and I both had summer jobs in the city so we would see each other on the subway and we would talk about music.”

Uppercut often played at the legendary rock club CBGB. They were inspired by the diversity and benevolent attitude of the arts scene, both on campus and in the city. “There was a strong thread that ran through that scene,” Murphy says. “There were a lot of benefits for Amnesty International back then, and a lot of movements to stop violence against the gay and lesbian community and just racism in general.”

By 1990, however, the hardcore scene was becoming exceedingly violent, Murphy says. “You didn’t see it so much in New York City at that time because it wasn’t acceptable, but when we would travel to Philadelphia or Allentown, there would be very uncomfortable confrontations between bands and neo-Nazis. So we stopped playing hardcore and started another band, which played an early grunge type of music, and that’s when Carl joined us,” Murphy says. “That lasted from 1990 to 1993, and we had absolutely zero success. In the hardcore scene, it was normal to play in front of hundreds of people every night that knew every word, and were stage diving. I didn’t appreciate it then. I just thought that’s how it was. I found out the hard way that’s the exact opposite of how it really is,” Murphy admits.

From Wall Street to the World

At that point, Murphy’s Wall Street career was becoming more demanding, and he no longer had time for the band. Porcaro and Sefcik kept playing in bands all the way through, but Murphy’s music career was on hold until 2005. His finance career took him to Paris and then London before he joined Rose Grove Capital, a hedge fund. “While I was in Europe, Carl and Rob were in a band called Electric Frankenstein based out of Jersey and they would tour there often, so we would always meet up when they came over,” he says.

In the early 2000s, the influence of the sonic seeds first sown by late ’80s New York hardcore bands sprouted anew with the explosion of the nü-metal genre. In 2005, Uppercut accepted offers to play reunion shows around the world, playing to larger audiences than ever before. Rekindling their musical camaraderie, Murphy, Porcaro, and Sefcik were inspired to write new material. Although their love and appreciation for hardcore remained intact, their musical direction shifted to favor a slower, darker, more earthen tonality. They took the name Kings Destroy in homage to the ’80s graffiti crew of the same name. In 2010, they released their full-length debut, And the Rest Will Surely Perish, and they’ve since cranked out two more full-lengths and an EP.

Murphy retired from finance in 2011, devoting his time to Kings Destroy. “Wall Street was always a means to an end,” he says, although he admits that the “rockstar lifestyle” isn’t what it used to be. The band takes a pragmatic approach to maintaining momentum in what Muphy calls “a needle-in-the-haystack industry.”

“You never know what will motivate a crowd base to get behind a band and push them to the next level or a couple levels up. The way we look at it is that we have to embrace the process of playing and writing, and if you don’t really love that process, it’s very easy to burn out on wanting things for your band that are just very unlikely to happen because there’s so much competition. But for us just to be able to go play in Europe or play in Auckland, New Zealand, is incredibly lucky, and we are fortunate to be able to do that.”

Lending a Helping Hand

Although their musical tastes have morphed through the years, at least one aspect of the hardcore ethos is embedded in everything they do: using their volume to amplify those who are not heard.

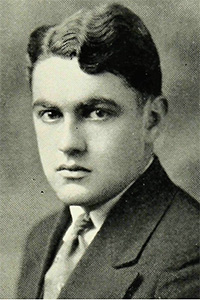

They’ve sponsored a youth basketball team from Brooklyn, and Murphy, who’s an active member of the executive committee of the Fordham President’s Council, set up a scholarship at the University. The Joseph Stephen Murphy, FCRH ’29, Endowed Scholarship Fund—named in honor of Steve’s grandfather—provides financial aid to help Bronx students who might not otherwise be able to afford a Fordham education.

The epitome of punk is to advocate for others without seeking recognition, and Murphy is characteristically humble about his philanthropy.

“My family has a long history in the Bronx, so it was natural for me to give back to the Bronx through the scholarship,” he says. “The type of kid that gets into Fordham probably has a chance of bettering themselves no matter what their socioeconomic background. I did it as just a little bit of a helping hand.”

—David Ciauro is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to Modern Drummer magazine.

Watch Kings Destroy’s video for “Smokey Robinson,” which Murphy has described as “a song about the struggle our country has with racism and oppression.”