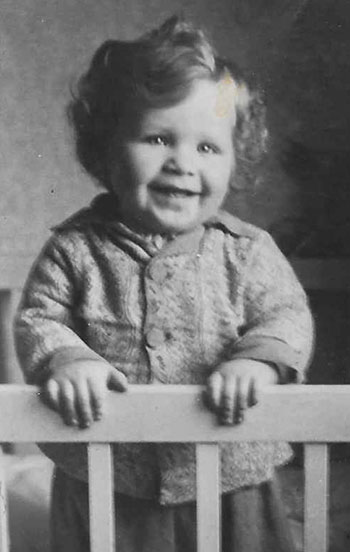

A child survivor of the Holocaust was reluctant to share his family’s full story, until he saw a picture of himself as a 4-year-old boy at Auschwitz on a website denying the Holocaust

For years, Michael Bornstein, PHA ’62, wished he could wash away the serial number—B-1148—that was seared into his left forearm when he was just 4 years old. He’d mention Auschwitz, if asked about the tattoo, but he wouldn’t dwell on the Nazi death camp where his father, brother, and nearly 1 million other Jews were murdered during World War II. He’d seldom speak of being separated from his mother, who withstood beatings from female guards as she smuggled bread and thin gray soup to him in the children’s barracks, and who later smuggled him into the women’s barracks before she was sent to a labor camp in Austria. He wouldn’t say much about how his grandmother somehow, improbably, kept him alive long enough for them to be among the 2,819 prisoners liberated by Soviet soldiers.

His recollection of those dark days is dim—“a blessing and a curse,” he says. He seems to recall the stench of bodies burning, the smoke rising from crematoria chimneys, the quickening clack of guards’ boots. But he’s also aware of the malleable nature of memory, how the things we recall, especially from early childhood, are shaped by some inscrutable mix of perception, imagination, and the stories we’re told. And so for years he stayed mostly silent about his past, not only because it was traumatic but also because so much of it—the texture of his brother’s hair, the sound of his father’s voice—was inaccessible to him.

He preferred to look forward, with an optimism he says he inherited from his mother. Gam zeh ya’avor, she’d tell him, quoting the motto she and her husband shared during the war. This too shall pass. He can still hear the sound of his mother’s voice because she found him in Żarki, Poland, after the war. In February 1951, when he was 10, they immigrated to the United States, where he’d go on to build a career in pharmaceutical research and—with his wife, Judy—raise four children in what he calls “a life filled with soccer games, birthday parties, and bliss.”

As his kids grew up, they began pressing him for details about his past, but he’d always resist a full recounting. Now Bornstein is 77, and his children have children of their own. Several years ago, when Jake Wolf, the eldest of his 11 grandkids, started asking questions, wanting to use the information for his bar mitzvah project, Bornstein couldn’t say no. He began to open up.

Then he saw something that left him stunned and more determined than ever to tell his story: a picture of himself as a boy at Auschwitz on a website claiming that the Holocaust is a lie, that it never happened. “I slammed my computer shut in disgust. I was horrified. My hands shook with anger,” he writes in Survivors Club: The True Story of a Very Young Prisoner of Auschwitz, published last March by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. “But now I’m almost grateful for the sighting. It made me realize that if we survivors remain silent—if we don’t gather the resolve to share our stories—then the only voices left to hear will be those of the liars and bigots.”

Bornstein wrote the book with his daughter Debbie Bornstein Holinstat, a TV news producer who for years had urged her father to work on such a project. She helped him plumb his earliest, darkest memories, and together they searched historical records and interviewed relatives and others who knew his family in Poland. In the process, they discovered a detail that helped solve one of the biggest mysteries of his survival, and he learned much about the resolute, resourceful father he never got to know. Together, they reclaimed a family heritage, illuminating stories of loss and resilience that had been left largely untold for 70 years.

Żarki, Open Ghetto

Michael Bornstein was born on May 2, 1940, in the Nazi-occupied town of Żarki, Poland, the second son of Sophie Jonisch Bornstein and Israel Bornstein, baby brother to 4-year-old Samuel. They lived in a redbrick house on Sosnawa Street.

In some parts of Poland during the late 1930s, Jews couldn’t own land, and their business dealings were restricted. But Jewish-owned businesses thrived in Żarki, where more than half of the town’s population, approximately 3,400 residents, was Jewish. Bornstein’s father was an accountant, and his mother’s brother Sam Jonisch (one of her six siblings) ran his family’s leather tannery in town.

That changed on Friday, September 1, 1939, when German forces invaded Poland, reaching Żarki the following day with an aerial attack that torched some homes and businesses. Sophie, newly pregnant with Michael, wanted to check on her parents, who lived nearby. But Nazi storm troopers had already moved onto the streets. On Monday, when all Jewish men in Żarki were ordered to report for labor shifts, Sophie left Samuel with her mother-in-law, Dora, and set out to find her parents. As she neared the Jewish cemetery, she saw German soldiers command a family she recognized from synagogue to strip naked. As mother, father, and young daughter huddled together, the soldier fired three shots, and the family fell dead in the ditch the father had just dug. It was a scene that haunted Sophie Bornstein her entire life.

The Nazis murdered more than 1,000 Jews in Poland that day, including 100 in Żarki. Such atrocities brought out the worst in some gentile residents, Bornstein and Holinstat write. “Many Catholics had not liked living among Jews before the war. Now they blamed the town’s Jewish people for making them the target of German bombings.”

In October, as Nazi soldiers went door-to-door confiscating Jews’ money and jewelry, Israel Bornstein sought to safeguard his family’s valuables. He gathered what he could in a burlap sack—a string of pearls, a stash of banknotes, the family’s small silver kiddush cup—and buried it in the backyard.

Żarki was still an open ghetto at the time, which meant that it wasn’t surrounded by fences, but Jews couldn’t come and go as they pleased. The Nazis shut down or took over Jewish businesses, enforced a strict curfew, and made Jews wear white armbands with a blue Star of David on them. They also forced them to create a Judenrat, a council of Jewish leaders. The town elders elected Israel Bornstein to serve as president. It was not a coveted role. Many Jews in Eastern Europe came to see Judenrat members as traitors, simply doing the bidding of the Nazis, and in Żarki people viewed Israel with suspicion.

But in their research, Bornstein and Holinstat found a collection of essays and a detailed diary written in Hebrew that told of Israel Bornstein’s heroic, often successful efforts to make conditions more bearable. In Survivors Club, they describe how he collected money from fellow Judenrat members and used the funds to bribe Gestapo officers, helping to obtain 200 legal travel visas for families trying to leave Żarki, for example, and saving the life of a teenager who faced execution because he was too sick to work one day.

“Though it’s sometimes seen as a very negative position, my father used it to save people. He set up soup kitchens. He was a very good man. And it made a lot of difference to me knowing that he was a good man,” Bornstein says. “That’s one reason we called the book ‘Survivors Club,’ because my mother’s six siblings all survived, and part of it has to do with my father, who encouraged them to go into attics, basements, wherever they could go to survive.”

By October 1942, however, the call had come for Żarki to be made Judenrein, “clean of Jews.” Most of those remaining were sent by train either to labor camps or to extermination camps. The Bornsteins and approximately 120 others were allowed to stay behind as part of a cleanup crew, but eventually they too were sent away, to a labor camp in Pionki. And in July 1944, when that camp closed, they were packed onto trains bound for Auschwitz.

“Sickness Saved My Life”

Upon arrival at Auschwitz, like all families, they were split up: Israel and Samuel were assigned to the men’s side. Michael initially stayed with his mother and grandmother until guards shaved his head and tattooed his arm. He was sent to the children’s barracks, where some older kids looked out for him, warning him to hold his nose as he drank down the smelly gray soup. Other kids stole his bread. Sophie was sent to the women’s barracks with Michael’s grandma Dora. She risked her own well-being to find her son and eventually bring him into the women’s barracks, where he hid under straw, in corners, scattering at the sound of guards approaching to take roll call.

While Sophie was able to protect Michael, she was helpless to save her husband and young Samuel, who died in September from the effects of Zyklon B gas—the Nazis’ preferred method of execution at Auschwitz, where as many as 6,000 people per day were killed in gas chambers. “[My mother] later told me that her heart literally felt like it had been gouged from her chest with an ax” when she learned of their fate, Bornstein writes. Soon, however, she was sent to a labor camp in Austria, and Michael was left alone with his grandma Dora.

By January 1945, with Soviet forces closing in on Auschwitz, the Nazis started to evacuate the camp, forcing an estimated 60,000 prisoners on what came to be known as a death march to concentration camps in Germany. Many prisoners, already frail from malnutrition, died from exposure in the harsh winter. But Michael and Dora evaded the march, and Bornstein always wondered how.

Not long ago, while visiting Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial museum in Israel, he discovered a document that solved the mystery. Nazi records indicate that he was in the infirmary at the time, diagnosed with either diphtheria or dystrophy (the writing is unclear). And his grandmother was with him. “The name doesn’t really matter,” he writes in Survivors Club. “That piece of paper recovered by a museum years after the war made one miracle clear. Sickness saved my life.”

On January 27, nine days after he found refuge in the infirmary, Soviet troops arrived. A couple of days after liberation, Dora carried Michael out to freedom, a scene captured on film by Soviet cameras. “Of the hundreds of thousands of children who had been delivered by train to Auschwitz, only 52 under the age of eight survived. They were the world’s best hiders,” Bornstein writes. “I was one of them.”

Postwar Dangers and the Cup of Life

Bornstein’s freedom brought with it a new set of dangers. “I would like to tell you … that all of us went home and lived happily ever after,” he writes. “But it wasn’t like that at all.” Four out of 10 Jews who survived the concentration camps died within a few weeks of the arrival of the Allied armies. Those who did survive found much of Eastern Europe unsafe for them, particularly in Poland, where anti-Jewish sentiments led to a series of murderous pogroms.

Soon after liberation, Michael and Dora returned to Żarki, where they found the family home on Sosnawa Street had been seized by a Polish family who now saw it as their home. Dora took Michael to a farm on the edge of town, where they found shelter in a chicken coop. They would periodically head into what had been the Jewish quarter, where they met relatives who were, miraculously, among the few dozen Jews (out of 3,400 six years earlier) to return to Żarki after the war. One day, as Michael and Dora walked in town, he spotted his mother, who had made her way back from Austria. “If we had both seen more horror than the world knew it could hold—then this moment was the opposite of that,” he writes. “This was the opposite of despair.”

Sophie realized that there was little opportunity left for them in Żarki. But first she tried to recover the valuables her husband had buried. “At night, even though the house was occupied, she went digging with her bare hands to try to find these things, jewels and money, and the only thing that she found was the kiddush cup, which is a cup that you make blessings with,” Bornstein says.

“And so this cup has been in our family ever since. It’s been at my wedding, at our kids’ weddings, at their bar mitzvahs, bat mitzvahs, and so on. It’s not worth much if you buy it for the silver, but we cherish it quite a bit.”

In Munich, Waiting on Passage to America

After the war, Dora decided to remain in Poland, but Sophie determined that she and Michael would apply for visas to the United States. “She said the word ‘America’ the way a child says the word ‘candy,’” Bornstein writes. “She told me America was the most wonderful and welcoming place you can imagine.” That was not the case for them in Żarki or in Munich, where the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society assigned them to a displaced persons camp and, later, to a one-room apartment in the city.

“The German kids were bullies,” Bornstein recalls. “I had no hair on my head, I was skinny, and I didn’t speak the language, so I was bullied quite a bit.” Sophie bought flour and nylons from American soldiers and sailors in Munich, and sold the goods on the black market. It was a risky way to make a living, and Bornstein feared that she’d be arrested and he’d lose his mother again. But after nearly six years, they received their visas and set off on the USS General M. B. Stewart, arriving in New York City in February 1951.

With help from aid organizations, they eventually settled in a small apartment on 98th Street and Madison Avenue. Sophie worked as a seamstress, making $30 a week, and Michael attended P.S. 6. “I was this little kid who didn’t speak much English and had a tattoo on his arm. The teachers didn’t say anything, so I was pretty much alone and didn’t have friends,” recalls Bornstein, who soon found a job that would prove to be consequential. “I worked at Feldman’s Pharmacy, at 96th and Madison, getting 50 cents an hour,” he says. “The head pharmacist, Victor Oliver, was very good to me. He kind of took me on as a father figure and sparked my interest in science.”

Oliver even attended Bornstein’s bar mitzvah, held at Park Avenue Synagogue, after which his mother gave him a gift that she’d been saving for years to buy him: a gold watch. “You have to wind it a few times a day to make it work, but it’s great,” he says. “And on the back, it has a gimel and a zayin, which are the Hebrew letters for gam zeh ya’avor, ‘This too shall pass.’”

“A Can-Do, Get-It-Done Type of Guy”

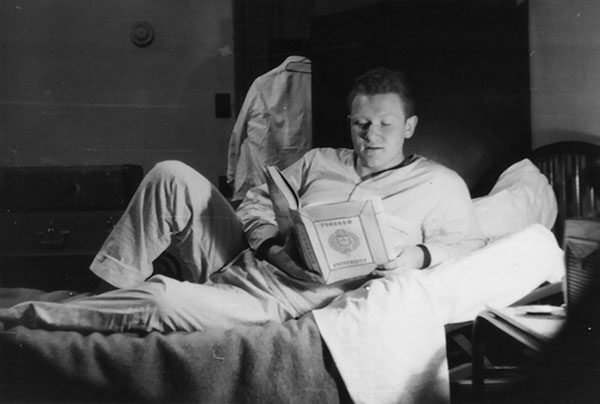

Bornstein’s mother also instilled in him a deep appreciation for the value of education. Like faith, she’d tell him, education can’t be taken away. In 1958, he enrolled at Fordham’s College of Pharmacy, just as she embarked on a new chapter in her life. “My mother remarried and moved to Cuba because her sister was there,” he says. She would later return to the States and settle in South Florida, but at the time, Bornstein says, “I was pretty much homeless, and Fordham didn’t have any room in the dormitories, so they put me up in the infirmary.” It was the second time in his life that an infirmary saved him, he says. “I would probably have skipped college if it weren’t for that.”

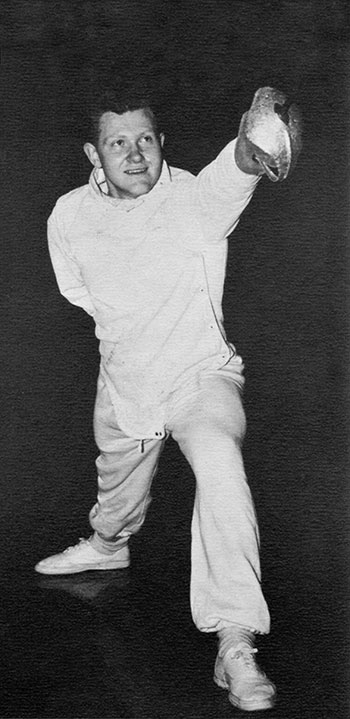

In addition to providing Bornstein with room and board, Fordham gave him a partial scholarship. He spent summers working in the Catskills to help pay any remaining tuition costs. “I was a chamber maid, then a busboy, then a waiter, and finally a head waiter,” he recalls. “The salary was only about twelve dollars a month, but the tips made it.” On campus, he found a niche on the fencing team.

One of his former Fordham classmates, William Stavropoulos, PHA ’61, recalls Bornstein as a “nice, friendly guy.” He says he and his friends in G House at Martyrs’ Court never would have suspected the horrors Bornstein had been through. “I remember distinctly sitting around one day and a guy asked Mike about his tattoo. He mentioned the camp and said his mother used to hide him here and there, keep him out of sight of the guards, but he didn’t say much else. He was always upbeat.”

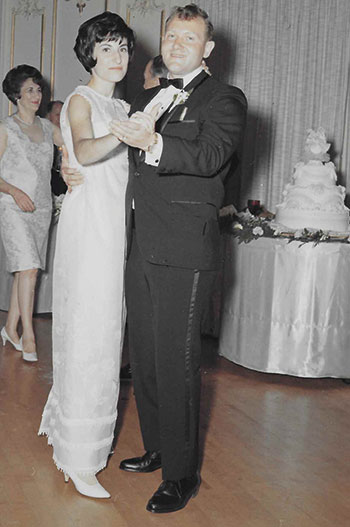

After graduation, Bornstein enrolled at the University of Iowa, where he earned a Ph.D. in pharmaceutics and analytical chemistry. But he says his greatest achievement there was meeting an undergraduate named Judy Cohan. “We obviously hit it off. He had the same interests I did, and he was persistent,” recalls Judy, who was studying special education. They attended movies and plays, and he accompanied her on visits to the children’s ward at local hospitals. “He was very caring of the children, and that was important to me.”

They were married nearly 50 years ago, on July 9, 1967, after Bornstein began his career at Dow Chemical in Zionsville, Indiana. While there, he reconnected with Stavropoulos, who had earned a Ph.D. in medicinal chemistry at the University of Washington and would go on to become chairman and CEO of Dow. The two, both newlyweds at the time, would see each other socially, and Stavropoulos even helped the Bornsteins move into their new apartment. But they lost touch over the years. “He went to work for Eli Lilly, and I stayed at Dow,” Stavropoulos recalls. In the late 1980s, Bornstein and his family moved to New Jersey, where he worked as a research manager for Johnson & Johnson, eventually rising to director of technical operations, a position that took him to Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, France, and elsewhere.

“He was a streetwise guy, and I always knew he was going to be a success,” Stavropoulos says. “When I think of Mike, I think of a positive, can-do, get-it-done type of guy. At Dow he was that way, and at Fordham too. It’s an incredible story. He’s obviously a courageous man.”

Fighting Intolerance with Compassion

Holinstat says her dad’s courage was especially evident during the process of writing the book. “My father is such a positive man, and he’s gone out of his way his entire life to show his kids and his grandkids nothing but positivity, so for him to dig deep and be willing to open up and talk to me about the deepest, darkest places in his memory was difficult for him, and it was hard for me because I knew how hard it was for him.” But the process has been well worth it, she says, explaining that they wrote Survivors Club with readers as young as 10 years old in mind.

“For my dad, a big piece of this was making sure that his grandkids understood the atrocities of the Holocaust. So it was really important to us to write something that the kids could grasp at this stage in their lives, and that they could share with their peers, because this next generation, most of them will grow up not having met a Holocaust survivor.”

In March, shortly after the book was published, it became a New York Times best-seller. The paper’s reviewer noted that the book combines the “emotional resolve of a memoir with the rhythm of a novel,” and that, although the book is marketed for young readers, “the equal measures of hope and hardship in its pages lend appeal to an audience of all ages.”

Holinstat waited decades for the opportunity to help her father tell his story, but she feels the timing of the book’s publication could not be more poignant or pointed, coming amid a recent surge in anti-immigrant and anti-Semitic sentiments in the U.S. “I truly believe that this story is being released now for a reason, to remind people what happens when bigotry goes unanswered,” she says.

The core moral lesson of the Holocaust, she and her father believe, is the ease with which any group of people can be dehumanized. “The world can never forget what happens when discrimination is ignored,” Bornstein said last April at Congregation Beth-El Zedeck in Indianapolis. “And it’s not just discrimination against Jewish people but against all minorities, and that includes Muslims, Mexicans, and African Americans. It’s time for compassion; it’s time for empathy.”

Bornstein plans to return to Poland this year with Judy, their children, and other family members. Holinstat has been communicating with people in Poland about establishing a Holocaust memorial in Żarki, and the family will be going to Auschwitz, which Bornstein visited in 2001 with Judy and in 2010 with his son, Scott.

In the meantime, Jake Wolf, the grandson who persuaded Bornstein to share his story, is preparing for his freshman year at Syracuse University, where he intends to major in both communications and business. “In our family,” he says, “it’s so important to know how difficult it was for my grandpa. He never had any hate toward the world for what he was put through. And that inspires all of us. If he could get through that with a smile on his face, we can do anything.”

A “Survivors Club” Reunion in the Suburbs

Since the publication of the book, Bornstein has heard from many people who have thanked him for telling his story, including some who understand all too well what he and his family endured. Sarah Ludwig was the 4-year-old girl standing next to Bornstein in the iconic photo from Auschwitz. Tova Friedman, then 6, stood just behind Ludwig as the children showed their tattoos to Soviet soldiers. The three survivors recently learned that they live just miles from each other in suburban New Jersey.

On Sunday, June 4, they gathered with kids, grandkids, and other relatives for a reunion brunch at Holinstat’s home that included prayers of remembrance and celebration, and the use of one precious silver cup. For Holinstat, it was a remarkable coda to the experience of helping her father tell his story after all these years.

“The last time they saw each other, they were kids wearing prisoners’ stripes,” she says. “Now they’re surrounded by family.”

—Ryan Stellabotte is the editor of this magazine.

Watch NBC Nightly News‘ coverage of the reunion.