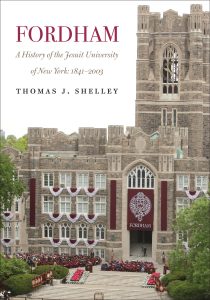

As a Bronx native, Monsignor Thomas J. Shelley, PhD, GSAS ’66, never needed an introduction to the Jesuit University of New York. “Every Catholic growing up in the Bronx was aware of Fordham and had a good impression of the University,” he says. But even after spending 16 years teaching at the University and publishing several books on the history of the Catholic community in New York City, he discovered much more while writing Fordham, A History of the Jesuit University of New York: 1841–2003 (Fordham University Press).

Monsignor Shelley, professor emeritus of theology at Fordham, began working on the book in 2008, shortly after completing The Bicentennial History of the Archdiocese of New York. That’s when his cousin Joseph M. McShane, SJ, president of Fordham, invited him to write a history of the University up until 2003, when Joseph A. O’Hare, SJ, GSAS ’68, retired as president.

This month, Fordham will begin a yearlong celebration of its dodransbicentennial, or 175th anniversary—and Monsignor Shelley’s history of the University has arrived just in time.

Could you tell us a little about the book? How did you tackle covering almost 175 years of history?

The Jesuits made my work easy because they carefully preserved so much of Fordham’s history in their archives, both here in New York City and also in Rome. Prior to 1907, Fordham (which was still called St. John’s College at the time) is the story of a small liberal arts college in the rural Bronx. After 1907, with the establishment of the first graduate schools (and the transition from college to university), the plot thickens. Each of the graduate schools has its own distinct identity and history, so the story becomes more complicated.

Did you make any surprising discoveries about Fordham or its historical figures in your research?

Yes, I did, and they were some of the most rewarding aspects of my research. For example, it is well known that Father Joseph Keating, SJ, was the University’s treasurer for 38 years, a period that spanned two world wars and the Great Depression. I did not know, however, that in 1912 Father Keating protested vigorously to the Jesuit father general in Rome when the general objected to the appointment of Fordham’s first Jewish dean, Jacob Diner, MD. Father Keating won the battle, and Dean Diner remained a much-admired dean for 20 years.

Another surprise for me was how significant the philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand was before he joined the Fordham faculty as a refugee from Nazi Germany. In Europe Hildebrand was an outspoken opponent of the Nazis and was an influential figure in reshaping Catholic thinking on the relationship of the Catholic Church to the Jewish people, an effort that bore fruit years later at the Second Vatican Council in the groundbreaking document, Nostra Aetate.

As a result of my research, I also came to the conclusion that one of the most underappreciated presidents of Fordham was Father Robert I. Gannon, SJ, who was president from 1936 to 1949. Father Gannon secured Fordham’s reinstatement in the prestigious Association of American Universities after his predecessor had lost it in 1935, upgraded academic standards, appointed the first woman graduate dean, and guided Fordham through the lean years of World War II and the challenges of rapid expansion in the postwar era. He was the first president of Fordham to become a prominent civic figure in New York City.

In the preface to the book, you describe how, in 1941, Father Gannon claimed that only two kinds of universities would survive in the United States—those that are “very rich” and those that are “indispensable.” Do you think that he was correct? Is Fordham “indispensable?”

I do not think that any American educator in 1941 could have foreseen the dramatic expansion that would take place in American higher education in the postwar world. With regard to Fordham, I think that one can make a convincing claim that in the past 75 years Fordham has established itself as an indispensable anchor in the network of Catholic and Jesuit universities in the United States. One of the main reasons that Archbishop John Hughes started Fordham was to provide an education for immigrants, and that is still a major part of the University’s mission. Throughout its history, Fordham has played an integral role in Catholic higher education in New York City. And it’s also one of the largest and academically strongest of the Catholic colleges and universities in the country.

What do you foresee for the next 175 years of Fordham’s history?

My mentor, the highly respected church historian Monsignor John Tracy Ellis, often said that he thought that historians were notoriously poor prophets and that they should always confine their comments to the past, not the future. I am of the same opinion.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Alexandra Loizzo-Desai.