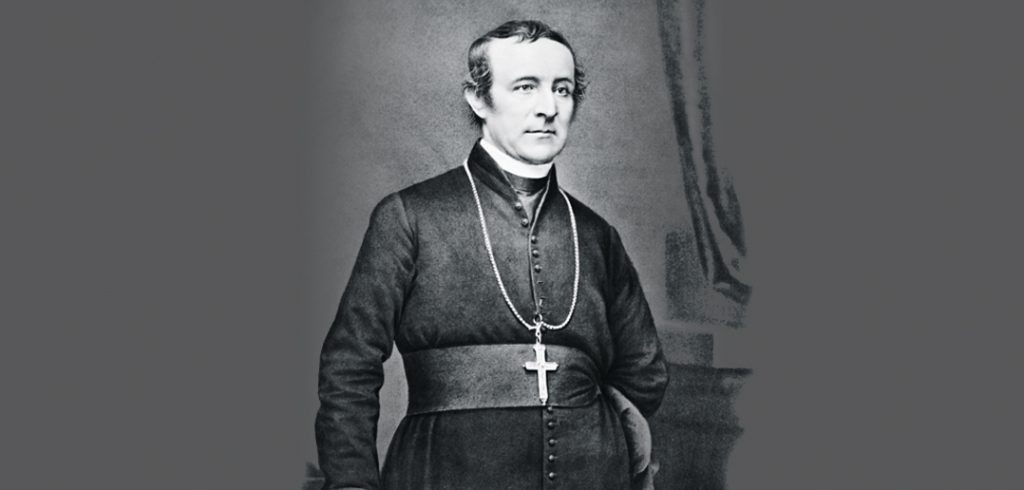

Then, while visiting the Rose Hill campus, he walked past the statue of Archbishop John Hughes—founder of Fordham, tireless advocate for Irish immigrants, and combative public personality who unabashedly pushed back against anti-Catholic prejudice of the mid-19th century, shocking some of his fellow clerics and earning nationwide fame.

Loughery had found his subject. “I do think he is a major player in 19th-century American history and had not been given his due,” he said. “I just knew this was a great story.”

Loughery tells that story in Dagger John: Archbishop John Hughes and the Making of Irish America (Cornell University Press, 2018). It covers the full scope of Hughes’ life, from obscure Irish immigrant to first archbishop of New York to confidant of U.S. presidents and player on the world stage. As Loughery describes, Hughes was warm-hearted and devout but also fierce and resourceful in service of his destitute, despised Irish immigrant flock. He raised funds prodigiously, founded schools and churches and orphanages, and met threats of anti-Catholic violence with fiery rhetoric about fighting back, with force if necessary. And he used his rhetorical gifts to publicly refute Catholics’ detractors at every turn.

Loughery tells that story in Dagger John: Archbishop John Hughes and the Making of Irish America (Cornell University Press, 2018). It covers the full scope of Hughes’ life, from obscure Irish immigrant to first archbishop of New York to confidant of U.S. presidents and player on the world stage. As Loughery describes, Hughes was warm-hearted and devout but also fierce and resourceful in service of his destitute, despised Irish immigrant flock. He raised funds prodigiously, founded schools and churches and orphanages, and met threats of anti-Catholic violence with fiery rhetoric about fighting back, with force if necessary. And he used his rhetorical gifts to publicly refute Catholics’ detractors at every turn.

Hughes fervently believed in his own brand of leadership and was ready and willing to be at the center of the storm, said Loughery, an English teacher at the Nightingale-Bamford School in Manhattan and award-winning author of four other books, including John Sloan: Painter and Rebel (Henry Holt, 1995), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

Tell me more about the problems he was up against.

When he came from Philadelphia to New York as coadjutor bishop in 1838, he was horrified—I don’t think he had a clue how bad things were going to be, that the churches were all in danger of foreclosure. And then the church burnings, the convent burnings—between the 1830s and the 1850s, there’s this enormous number of books about the pope’s supposed plans for America, and how the undermining of American democracy is underway with all these Catholics coming in. It probably was not a view most American Protestants supported, but the anxieties were real enough. And the poverty of the Irish coming into New York was a significant problem. The number of people pouring off those boats during the years of the Irish potato famine was colossal. The slums exponentially grow and people start to think, our city is being overrun. There’s the rise of a fundamentalist Protestant movement that wants to say, “We are under attack.”

How did Hughes respond?

His job, he felt, was to make sure these new people coming in do find jobs, they do go to church, they do become reputable citizens. He believed that without the church, the Irish Catholic immigrant was going to be lost, that without some sort of bedrock faith, we as Americans were headed in a very dangerous direction. I think he consecrated a hundred churches in his time. He tried to found churches right and left, and he said even more important than putting in the church building, the priest there should be working to get a parochial school going. He was absolutely devoted to the idea that education was the way out of poverty.

So he’s constantly trying to fundraise and get more priests to come in and get more teachers and get more nuns to come work here, and he’s trying to get a university like Fordham going. It’s amazing he lived to his 60s, that he wasn’t completely worn out by this superhuman effort.

There’s one record of him talking in downtown Manhattan and raising $1,500 dollars that night, a colossal amount of money, for a church-basement grammar school. He was a very popular lecturer; people knew he was the fighting bishop. He was the face of Catholicism in America. He was somebody who had gone to Europe and met the kings and the popes. So he cultivated a colorful, dynamic, charismatic personality, and he had a great speaking voice.

He also felt the need for a kind of public relations campaign where we show what good citizens we can be, and so he’s very involved with courting politicians and being courted by them, trying to get himself seen as helpful to people in power.

How did he break the mold?

I think a lot of bishops were astonished that John Hughes came in and said every insult, every question, every attack [against Catholics]will be met head-on, we will not look the other way. And some of them felt, “You’re making things worse. If we didn’t have to answer every criticism, we didn’t have to constantly be on the barricades, we might be getting along with Protestants better.” And then he gave this speech in 1850, “The Decline of Protestantism and its Causes,” and had many bishops saying, “What in the world do you need to take these people on like that for?”

He was not a pacifist, unlike many other bishops who did turn the other cheek when the church or convent was burned in their area or rioters threatened them. He felt Americans only respect you if you fight back, so he was definitely a more aggressive person.

Was he more than just the “fighting bishop”?

There were gentler sides to him. There are so many letters in the archives from priests and parishioners thanking him for his help and concern, and that’s a part of him you don’t see in most other accounts of his life. He definitely has been stereotyped as belligerent and egocentric. There was a woman named Sophia Dana Ripley who converted and was uncertain whether she would be a good Catholic or not; he would take people like that under [his]wing and explain that God accepts you as you are, that the church understands frailty and human nature and exists to help bring you into the embrace of God. He really could reach out to people in ways that he doesn’t get credit for.

Was he a creature of his times?

So many bishops of the time didn’t know how to deal with all these problems, so they would try to placate those groups they could. He was the sort of person who just said, “No, this is not acceptable, I’m going to launch into every battle on every front I have to.” That sort of person is indeed pretty rare, and the legacy of someone like that will always be contested.

It was a completely different time. He was inventing things out of whole cloth. There were no roadmaps for what he was doing in this country, for how to make it work. He was an innovator, with all the flaws and greatness that that implies.

Related: Below is a video on Fordham’s participation in the 2018 St. Patrick’s Day Parade in New York City. Read the news story.