For Keefe, a 2008 Fordham College at Lincoln Center graduate, her brother’s death was both a painful personal loss and a wake-up call to the systemic failures—criminalization, pharmaceutical profit-chasing, lack of patient-centered addiction treatment—that had contributed to so many tragic endings like Matt’s. In the year following Matt’s death, Keefe moved to Brooklyn and began spending a lot of her time researching addiction issues, leading her to a job at the nonprofit Shatterproof. She also began training for the Brooklyn Half-Marathon. She had been a casual runner before that, but had never run a race that long, and the training offered her an opportunity to find both physical release and a healthy form of repetitive structure—“a connection to both the grief experience and the addiction experience,” she says.

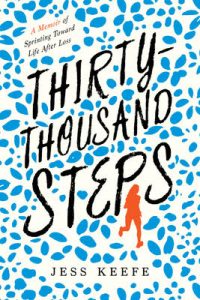

In her memoir, Thirty-Thousand Steps (Prometheus Books, 2022)—a reference both to the approximate number of steps in a half-marathon and to the 12-step addiction treatment model—Keefe pays tribute to her brother Matt’s life, takes a deep dive into the medical and political changes needed to address the addiction crisis, and recounts her half-marathon training as a form of catharsis. She hopes that it will reach others who have lost siblings or peers to addiction.

Keefe recently spoke with Fordham Magazine about her first book, her running practice, and the space for optimism about the future of addiction treatment.

Your parents are in the book a lot and come off as very kind, loving, supportive people. How supportive were they, and how much did you involve them in the process of writing the book?

They’ve been very supportive. It’s difficult for them. Neither one of them read it completely through, but they’ve had friends tell them about it and they’ve been excited and supportive and happy to hear that people like it. I wanted to be clear in the book: This is my story about me and my brother. This is our story. But I didn’t want to pretend my parents weren’t there when they were. They were in the hospital, they were helping him in every way that they could. There is so often that idea that it’s the parents’ fault or whatever, and that was never something I wanted to play into or give any air to—that they were absentee or didn’t love him or weren’t present for him.

But I didn’t want to get too into what their perspective was, because that just wasn’t the story I was equipped to tell. Part of what made me want to write this book so badly is I felt like there’s not a lot of writing for peers, siblings, friends, spouses who have lost people to addiction. We’re losing people at a really alarming rate. I felt like there was a big hole for people like us who are watching someone our own age go through this and thinking, “Why is it them and not me?”

Following Matt’s death, you got a job at the nonprofit Shatterproof, which focuses on addiction issues, and you still do consulting for them. How did your work with the organization overlap with the things you wrote about?

It was a huge opportunity for me to learn from people who are familiar with the policy space, people who are familiar with the treatment landscape, people who are familiar with government institutions that create regulations. That was a hugely eye-opening experience and really helped me synthesize one of the most straightforward messages of the book: that it can’t be overstated how much is known and understood about addiction right now and how little of it is utilized in medicine.

We do know what works, but also, one size doesn’t fit all. There’s no one treatment that’s appropriate for everybody. Addiction is such a specific condition that comes from such a specific psychosocial background of each person. And I think that’s what I tried to show in the book, too, with my brother and I being three years apart, right next to each other all the time, with a very safe, comfortable life, and one of us going this way and the other one going that way.

You can torture yourself trying to ask, “How could this have been prevented?” I think it’s more about if and when this does happen—because it does happen to people—here’s how you can react and here’s how people can get better. When he was sick, I was just waiting for the other shoe to drop the whole time, which is horrible. I wish I had had a better understanding of this being a treatable condition. The nonprofit work that I did gave me such an incredible view into the way that both medicine and government handle this—what they think the approach has been and what the approach should be.

Were there moments when it felt too emotionally difficult for you to push through with the practical elements of research and writing?

I think the way that the trauma manifested for me was not like, “Oh, I can’t look at this.” It was almost like, “I’m looking at this too closely. I’m spending too much time on this.” I think there are a lot of ways that you can react to an event like this in your life. Not wanting to engage with it very much makes a ton of sense to me. And I almost wish that had been my reaction, but I had the opposite reaction, which was like, “I’m so obsessed with this, I must do something.”

It was more a question of, “How do I synthesize all of this raw information into a coherent story? How can I make this intense degree of emotion something that a reader would choose to engage with?” You have to ask some hard questions, like, “Would I choose to read this if this is going to be non-stop suffering? Is this something that appeals to someone for 200-plus pages?”

One way you do make people want to engage with it, I think, is through humor. Along with all the really serious issues you write about, you also tell some really funny stories about growing up with Matt and are able to use self-deprecation when talking about how you grieved. How did you think about the ways you wanted to include humor?

It’s the way that everybody uses humor in their normal life—when you feel like the pressure’s building too much and you need just a little release. That would be when I would try to reach for the humor. And also to let people know that I’m okay—they don’t have to worry about me. I’m describing something that’s very horrible, but I’ve had enough time to zoom out that I can even make a joke. So you can laugh too, it’s okay. We’re all kind of going through this together. But you definitely need the people around you to tell you when something’s working and when something’s not.

How far do you think we have come in terms of treating addiction since you started the project? Have you seen progress in terms of things like safe consumption sites and people knowing more about the issues?

I feel like there’s so much stuff going on that would’ve shocked me five years ago. Fentanyl test strips, Naloxone being in music clubs underneath the bar, being a tool that people are prepared to use or at least theoretically know they should be prepared to use—that’s huge. I didn’t even know what Naloxone was in 2015, when I was living with someone with an active heroin addiction. I think at the very least, now people understand that this is out there.

There’s just a comical amount of unnecessary restrictions on addiction treatment. When you look into what the root of that is, it really is just nothing more than stigma and misunderstanding. There’s an impression that people with addiction have a certain moral character and that might make them riskier to treat. And that’s obviously just not true. And so now, after it was part of the omnibus bill, it’s easier for doctors to prescribe buprenorphine, which is the gold standard medication for people who have an opioid use disorder. So I think that aspect is definitely improving.

The thing that continues to be frustrating is having these little pieces of hope within a larger system that is cursed. As long as we have a for-profit medical model, and as long as addiction is criminalized in the way that it is, these issues will persist. So I think that we’re chipping away at it, and I think that that’s nothing to be diminished, but the overdose rates now are even higher than they were when I started writing the book.

You recently did a reading at the bookstore Politics and Prose in Washington, D.C. How was that event?

It was really great—a full house, a very engaged audience. It was similar to the experiences I would have when I would be representing Shatterproof and going to public places, and you get people that kind of come up to you and put their arm on you and just really need to blab. They need to talk to somebody. And I think when people see somebody who is willing to talk about addiction in a public way, they see that as a way to engage with this thing that maybe they haven’t felt comfortable engaging with before.

Are you still an avid runner? Is that something that you still use to keep yourself centered as difficulties and challenges and tragedies occur in life?

I’m still a very avid runner. I completed my 10th half-marathon in the fall and I did my first full marathon in Los Angeles in the spring. It’s hard to overstate how very important running was to me. And I didn’t even really realize it at the time. It is very much a first line of defense coping mechanism for me. The physical element—I’m a very high-energy, anxious person, so if I don’t have an outlet for that, it’ll be a problem. So that has persisted and definitely continues to be important. Before I ran, I feel like I would roll my eyes at fitness content. So I hope people, even if they’re not into running, they’ll check it out, because the purpose of me including that was to show, “Here’s the power of finding something that works for you.”

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Adam Kaufman, FCLC ’08.