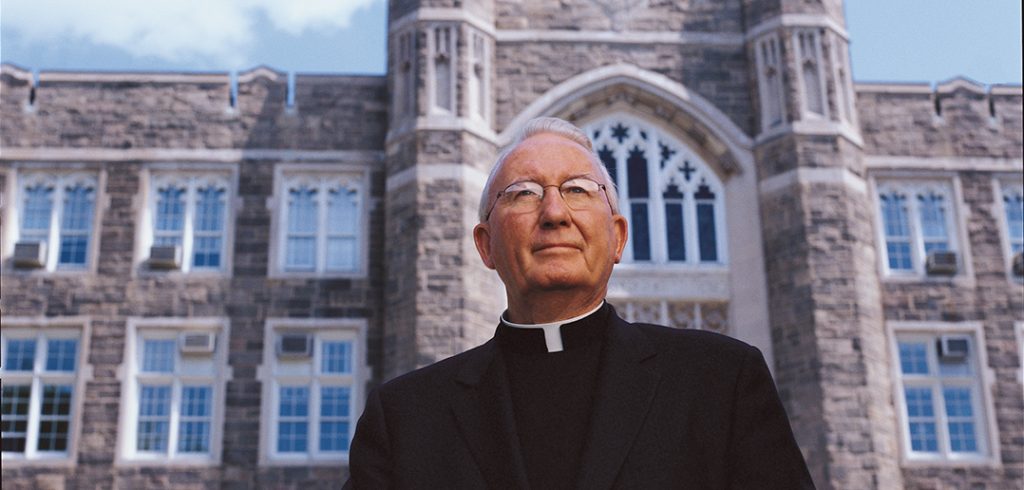

When Father O’Hare announced his plan to retire at the conclusion of the 2002-2003 academic year, the Rev. J. Donald Monan, S.J., former president and current chancellor of Boston College, said of Fordham University’s longest-serving president: “His early years as a Jesuit in Asia gave him a unique perspective on American culture, but his native New York gave him a directness, a maturity and a no-nonsense wisdom in leading that has reshaped the face of Fordham.”

***

If Rip Van Winkle had fallen asleep at Rose Hill or Lincoln Center one peaceful July evening in 1984, and suddenly rose from his slumber this summer, he’d wake to find a Fordham University transformed in powerful and lasting ways. But unlike the Washington Irving character (who actually slept a full 20 years), this modern-day Rip would not find his house “gone to decay.” Instead, he would find a University physically expanded, academically and spiritually renewed, and, more than ever before, a prominent player in shaping the destiny of the global city it calls home.

A New Landscape: Lincoln Center, Rose Hill, Marymount

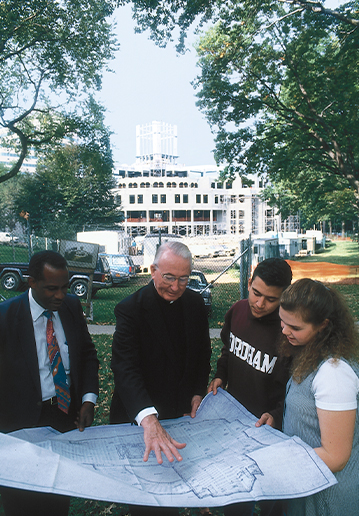

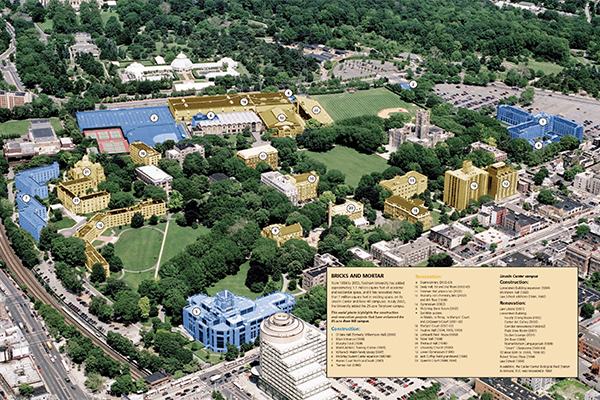

Since 1984, under Father O’Hare’s leadership, Fordham has been engaged in an expansive building program that has seen the addition of approximately 1.1 million square feet of new academic and residential space, and the renovation of more than 1 million square feet of existing facilities. To put those statistics in historical perspective: the University added approximately 102,500 square feet of new construction from 1974 to 1983. Not since the tenure of the Rev. Laurence J. McGinley, S.J. (1949-63), when Fordham acquired the seven-acre plot that became the Lincoln Center campus, has the University achieved such profound growth.

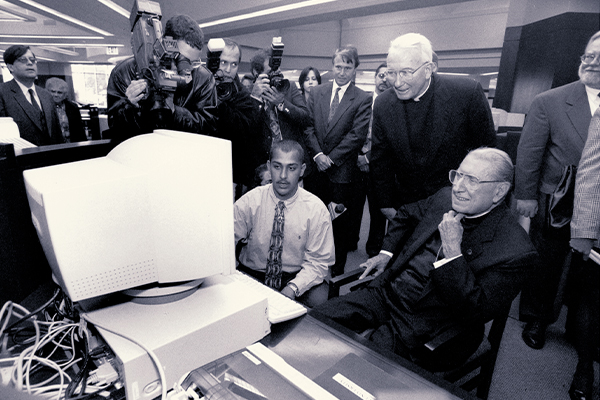

The crowning achievement during this recent period of growth was the construction of the William D. Walsh Family Library, which opened in 1997. Ever since Father McGinley took office in 1949, Fordham presidents had hoped to build a world-class university library. Father O’Hare was determined to move those hopes into the realm of action. With tremendous support from trustees, administrators and benefactors, he built something more than a major academic facility. Walsh Library is a neo-Gothic symbol of the University’s commitment to academic excellence, its reverence for the past and its faith in the future.

“Father O’Hare leaves behind a record of expansion and building that any of his predecessors might envy,” said Msgr. Thomas Shelley, associate chair of the Department of Theology and co-editor of The Encyclopedia of American Catholic History. “The opening of the Walsh Family Library fulfilled a dream of generations of Fordham students and faculty and gave us one of the most sophisticated university libraries in the country.”

Students, it seems, agree with Msgr. Shelley. In the 2003 edition of The Best 345 Colleges, the Princeton Review ranked Walsh Library number six in the country based on student assessments of library facilities. In addition to being the highest-ranked Jesuit university, Fordham placed ahead of Yale, Columbia and Harvard.

But Walsh Library is by no means the only legacy of the last 19 years.

More than a decade before the opening of the library, Father O’Hare began reshaping the face of the University in ways that facilitated growth. The construction of four residence halls at Rose Hill—Tierney Hall (1986), Alumni Court North and Alumni Court South (1987), and Millennium Hall (2000)—and the completion of McMahon Hall, the 20-story residence on the Lincoln Center campus (1993), enhanced the undergraduate experience, transforming the University from one largely attended by commuters in 1984 to a dynamic residential community of 3,756 students in 2002-2003. Millennium Hall, the newest residence, opened its doors to more than 400 students in August 2000. Not simply a dormitory, it features meeting spaces and study lounges that enhance the interconnectedness of academic, residential, spiritual and social life at Fordham. It is most fitting, then, that Millennium has been renamed O’Hare Hall, and will be dedicated as such at a Homecoming ceremony this September.

As a result of Fordham’s transformation from a commuter school to a predominantly residential community, the University has been able to attract an increasingly national and diverse student body. In 1984, students hailed from 26 states and only a handful of foreign countries; today, they come from 48 states and 48 foreign countries.

Applications for admission to the University’s undergraduate programs, which totaled 4,064 in 1984, have nearly tripled. There were some rough patches—in the early 1990s, applications dropped so precipitously that enrollment fell by 20 percent—but since 1991, with the help and hard work of the admission team, Father O’Hare led a complete turnaround. Fordham’s growth has exceeded national trends. In 1998, the New York Times wrote: “Faculty members say that the growing popularity of New York City as a college destination and Father O’Hare’s insistence on academic excellence are the major reasons why the number of applications to the school is double what it was in 1991.”

This year, the Office of Undergraduate Admission received more than 12,800 applications from potential members of the Class of 2007—an increase of 1,500 from last year’s total. Approximately 52 percent of the applicants were admitted, bringing the University’s acceptance rate down 3 percent from last year.

As the applicant pool has grown in the last decade, the academic profile of each class has also steadily improved. For example, on average, the SAT scores of incoming freshmen have improved by approximately 100 points in the last decade. This trend was highlighted by the Wall Street Journal in a March 30, 2001, article about college admissions. The Journal called Fordham a “hard-charging institution,” one that is increasingly selective and competitive, and predicted that the University’s acceptance rate (which was 65 percent in 1984) would drop to 50 percent in five years. Based on the latest statistics, Fordham is outpacing that prediction.

In addition to building residential facilities at Lincoln Center and Rose Hill and working to increase enrollment, Father O’Hare added a third campus, expanding the University’s undergraduate opportunities to include a women’s liberal arts college in the Catholic tradition.

Since the 1970s, the Marymount College campus in Tarrytown, N.Y., had hosted some of Fordham’s graduate-level classes in social service, education and business administration. Building on that relationship, Marymount College consolidated with Fordham on July 1, 2002, to become the University’s 11th school and fifth undergraduate college. Founded in 1907 by the Religious of the Sacred Heart of Mary, Marymount College of Fordham University, as it is now known, is situated on a hill overlooking the Hudson River (not far, incidentally, from the fictional village in the Catskills where Rip Van Winkle took his famous nap).

When the consolidation agreement was announced in December 2000, Father O’Hare asked Mary Ann Quaranta, D.S.W., who had recently retired after serving for 25 years as dean of Fordham’s Graduate School of Social Service, to become Marymount’s provost and to assist with the union.

“The recent consolidation of Marymount College with Fordham University provides Marymount students with the best of two educational worlds,” Quaranta wrote last December in Women’s News. “They are able to partake of the academic and administrative resources available at a major university while at the same time studying among only women at a small, largely residential, liberal arts college.”

This “experiment in Catholic higher education,” as Father O’Hare has called it, has attracted positive attention. In a June 6 article titled “Merging Without Overpowering,” The Chronicle of Higher Education described the Fordham-Marymount experience as a potential model for future college mergers, lending support to the hope that smaller schools “don’t have to give up all that makes them unique in exchange for survival.” Like nearly all women’s colleges in recent years, Marymount had been struggling to recover from financial troubles caused by a decline in enrollment. Since the merger, the college has enjoyed a steady increase in enrollment while retaining much of its identity. Applications for the Class of 2007 surpassed 1,600, nearly twice the number the college received two years ago.

Renewing Undergraduate Education, Pursuing Academic Excellence

In the spring of 1994, Father O’Hare led a major initiative to strengthen undergraduate education at Fordham. He urged the Board of Trustees and the faculty to help ensure that students could take full advantage of the complementary strengths and distinct opportunities available to them on both the Lincoln Center and Rose Hill campuses. At the time, he wrote, “To put the issue in the shorthand of advertising: Should our admissions literature speak, as it has in the past, of Fordham: Rose Hill or Lincoln Center? Could we not, instead, invite students to experience Fordham: Rose Hill and Lincoln Center?”

After 18 months of discussions, the faculty brought together Lincoln Center and Rose Hill as never before. The liberal arts faculties were restructured and unified, and a common core curriculum was established at the two campuses. This has made undergraduate education at Fordham a richer and more consistent experience. Previously, the undergraduate liberal arts colleges had separate requirements. Now, the common core makes it easier for students to use both campuses. It also more strongly reflects the University’s Jesuit identity, with an emphasis on critical thinking, personal attention, service to others and ethical leadership. In addition to taking courses in a broad range of subject areas, all students in their senior year take an interdisciplinary seminar in values and moral choices.

During Father O’Hare’s tenure, student-faculty collaboration was at the heart of the Fordham experience. In the last decade especially, the University has been placing greater emphasis on preparing students to apply for highly competitive post-graduate fellowships and scholarships. Faculty and administrators work one-on-one with students, challenging them to achieve a standard of excellence they may not know they can reach. Father O’Hare’s successor as president, the Rev. Joseph M. McShane, S.J., was especially involved in this cultivation process when he was dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill and professor of theology from 1992 to 1998. Under the direction of the Office of Prestigious Fellowships, more than 80 undergraduate and graduate students have received prestigious awards in the last eight years.

Fordham’s commitment to scientific education and research is reflected in the 1993 renovation of the Louis Calder Center Biological Field Station, a 114-acre site in Armonk, N.Y., and in the more recent renovations of the biology, physics and chemistry labs on the Rose Hill campus. At the Calder Center, graduate and undergraduate students in field biology have the opportunity to conduct hands-on research with Fordham scientists. The Research Science Fellows Program, which was launched 10 years ago, also encourages student-faculty collaborations and promotes awareness of career opportunities in research.

Unlike many universities, Fordham requires its undergraduate science majors to conduct laboratory research with faculty members. This type of partnership, which bolsters the student’s resume and supports the valuable work of the faculty, has yielded significant benefits. For example, in December 2000, a team of Fordham researchers identified the cause of familial dysautonomia, a genetic disorder that affects one in 30 individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. The Fordham team, which consisted of two senior scientists, four molecular biology graduate students and one undergraduate student, published its findings in the American Journal of Human Genetics in 2001.

Another hallmark of Father O’Hare’s presidency has been his dedication to the creation of scholarship opportunities. Even as the University has become more academically selective, it has aimed to remain economically accessible to gifted and deserving students. Since 1984, more than 225 scholarships have been established (bringing the total to more than 400), and though they are as varied as their generous donors, they all share a common goal: to provide financial opportunity for students who might not otherwise be able to attend Fordham. Not coincidentally, this was also one of the top priorities of the Fordham University Campaign, the most successful fundraising initiative in the University’s history to date.

Keeping Faith with the Future: The Fordham University Campaign

When the William D. Walsh Family Library was dedicated on Oct. 17, 1997, CBS News veteran Charles Osgood (FCO ’54) spoke about the component parts used to create the 240,000-square-foot building: “Brick and mortar, a lot of stone, metal and glass,” he said. “But there are other elements—faith in this university and what it stands for, hope reinforced by prayer, dedication and love. It took a lot of love to make this building…and money, which wouldn’t have come without love.”

Little more than a month later—appropriately enough, on the night before Thanksgiving—the Fordham University Campaign exceeded its $150 million goal by $5.6 million.

When it was formally announced in 1991, the University’s sesquicentennial year, the campaign was the largest of its kind for a Jesuit university. The previous summer, during his Jubilee address to alumni in the McGinley Center Ballroom, Father O’Hare set the tone for the campaign.

“The theme we are picking for our 150th anniversary,” he said, “is Fordham: Keeping Faith with the Future. The idea of that is to look in the traditions of the past to try to find the creative response to the challenges of the future. My assumption is you can betray your faith, religious faith, personal faith, academic faith…by trying to hold on to some frozen moment of the past. You have to keep your faith alive by bringing it forward into the future.”

Nearly one quarter of all alumni showed their faith in Fordham by participating in the campaign. More than two-thirds of the $155.6 million raised came from individuals—undergraduate and graduate alumni, parents and friends—many of whom had not had a previous connection to the University. They helped to create 170 new endowed scholarships for undergraduate study as well as the study of law, graduate education, business, and the arts and sciences. Faculty chairs were established in several areas, including law, religion and social service. Through their gifts, alumni and friends produced a groundswell of enthusiasm for the University’s promise.

Of the campaign’s many successes, two particular achievements will continue to have a profound impact on generations of Fordham students and faculty in the 21st century: the stellar growth of the University’s pooled and long-term investments, which surpassed $200 million by the end of 1997; and, of course, the William D. Walsh Family Library, the signature building of the Fordham future. The library cost $54 million to build. It was financed in part by a $9 million grant from New York State and $17 million donated by Fordham alumni and friends, including a $10 million gift from William D. Walsh (FCO ’51).

In an interview during his first days as president, Father O’Hare expressed two concerns about his role as a fundraiser: “One, that I won’t like it,” he said. “Perhaps even more serious, [I fear] that I’ll like it too much.”

The evidence suggests that such worries were unfounded; he somehow managed to strike the right balance. During the recent Faculty Senate dinner honoring Father O’Hare, Berish Rubin, Ph.D., professor of biology, praised Fordham’s 31st president for placing ultimate value on the University community and the people who make up that community.

“He insisted that compassion, not cash flow, serve as the rudder for this institution,” said Rubin, who served with Father O’Hare on the audit and finance subcommittee of the Board of Trustees. “He counseled the Board that they needed to understand that what was best for higher education, and not necessarily for the bottom line, was often most important. Father O’Hare knows the importance of community, collegiality and compassion in an institution born of such a distinguished tradition.”

Still, Father O’Hare’s record as a fundraiser is impressive by any standard. By May 2002, when he announced his intention to retire, the University’s endowment had grown from $36.5 million to $271.6 million and annual giving had risen from $5 million to $40 million.

“As a result,” said Paul B. Guenther, chair of the Board of Trustees, “Fordham stands on a much higher threshold for the next stage of its development.”

New York City’s Jesuit University

One of the ways Fordham will continue to “keep faith with the future” as it enters the next stage of its development will be through its relationship with New York City.

For more than 160 years, the histories of New York City and Fordham University have intersected in many interesting ways. John Hughes, for example, founded St. John’s College in the village of Fordham in 1841 and later became the first archbishop of New York. John McCloskey, the first president of what was to become Fordham University, also served as archbishop of New York; he later became the first American cardinal. Although Father O’Hare has not held or sought ecclesial office (despite the fact that The New York Times recently referred to him as a “Jesuit prelate”), he has been an indispensable voice in Catholic higher education and a much respected civic leader.

In his inaugural address on Sept. 30, 1984, Father O’Hare sounded the keynote for his administration: Fordham, New York City’s Jesuit University. He issued a challenge to faculty, students and administrators, urging them to become more fully engaged with the life of New York City.

“The city, pulsing with the dilemmas of everyday existence, an arena for competing ambitions and inarticulate dreams, reminds the university that the pursuit of knowledge and truth cannot be merely a private pleasure,” he said. “The university, on the other hand, guardian of the wisdom of the past and seeking the shape of tomorrow, must be both the critical conscience and the creative consciousness of the city.”

During the last 19 years, the University’s interactions and partnerships with New York City—its businesses, schools, government agencies and community organizations—have grown in various ways. The city continues to provide rich resources for learning as well as unparalleled internship and employment opportunities. Through the Office of Career Planning and Placement, for example, more than 600 hundred employers visit Fordham each year to recruit potential employees.

In addition, the University has launched and expanded a number of initiatives that reflect a steadfast commitment to serve the city’s less fortunate. Since 1991, the National Center for Schools and Communities has been bringing together social workers and educators to improve the lives of at-risk students in elementary and middle schools. Students at the Law School volunteer more than 70,000 hours of pro-bono work every year. Through the school’s nationally recognized Public Interest Resource Center, these future lawyers participate in such projects as advocacy for victims of domestic violence, death penalty defense, and housing and immigration advocacy.

Undergraduates have also responded to the call to service. In 1985, the Office of Government and Urban Relations created the Community Service Program, which has been both a catalyst and a clearinghouse for community service opportunities. Each year, more than 700 students participate in the program, volunteering their time and skills to mentor and tutor schoolchildren, deliver food and clothing to the homeless in the Bronx and Manhattan, and work in local soup kitchens, to cite a few examples. Expanding on this tradition, the University recently launched the Service Learning Program, which gives students the opportunity to receive additional credit for completing 40 hours of community service in an area related to their classroom studies and for writing reflection papers chronicling their work. Another example of Fordham’s commitment to serving its neighbors is the University Neighborhood Housing Program (UNHP), which helps to create, preserve and finance affordable housing for lower- and middle-income families in the northwest Bronx. In 2001, the Building Just Communities campaign of the U.S. Jesuit Conference honored UNHP as a model program.

Father O’Hare’s own civic involvement helped to set the tone for this renewed emphasis on strengthening the University’s commitment to the city. He has served on the boards of several institutions and on a number of city commissions. But he is perhaps best known for his work as the founding chair of the New York City Campaign Finance Board, an agency that has been hailed as a national model for campaign finance reform.

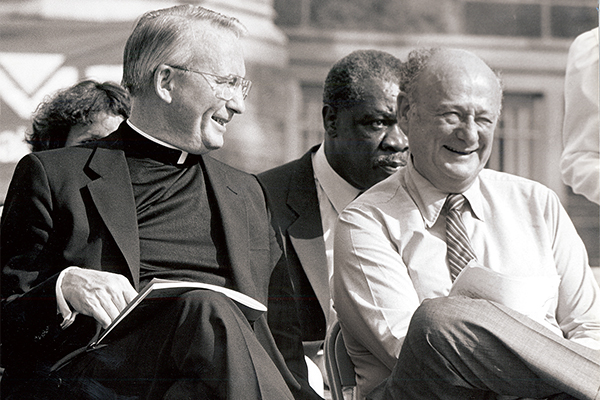

“He made the job,” said former Mayor Edward I. Koch, who first appointed Father O’Hare to the position in 1988. “It could’ve been a nothing job if it didn’t have a superb leader willing to take on every single person in politics. … I’ve learned that the occupant of the job defines the job. The job doesn’t define the occupant.”

Like the Rev. John Corridan, S.J., the labor priest who served as the model for Karl Malden’s character in the classic film On the Waterfront (see story on page 6), Father O’Hare quickly gained a reputation in New York City politics as a principled advocate for social justice. In 1992, he received the annual Civil Leadership Award from the Citizens Union of New York, and two years later the Conference on Government and Election Reform honored him for distinguished achievement in the regulation of government ethics. New York Post columnist Jack Newfield called Father O’Hare “the conscience of campaign finance reform and walking gravitas,” ranking him 44th on a list of “New York’s 50 Most Powerful People” in 1997 (two notches behind hip-hop mogul P. Diddy, but two ahead of Yankees owner George Steinbrenner).

One year later, during his 50th year as a Jesuit, Father O’Hare told The New York Times that he decided to enter the Society of Jesus largely because he was inspired by the active faith of Father Corridan and the labor priests. “It’s not an otherworldly kind of spirituality,” Father O’Hare explained. “It’s the kind very geared to involvement in the present time.”

Last February and March, in honor of Father O’Hare’s 19 years of dynamic leadership, the University hosted the Fordham and the City lecture series. During two evenings of lectures in the Law School’s McNally Amphitheater, historians and authors examined the links between the histories of New York City and the University, and they also acknowledged Father O’Hare’s major contributions to the latest chapters in both historical narratives.

In a March 16 lecture titled “Fordham and the Rise of Gotham: City of God and City of Man,” Peter A. Quinn, Ph.D. (GAS ’75), explored the distinct yet related histories of three New Yorkers. Quinn, author of Banished Children of Eve: A Novel of Civil War New York, told the stories of Archbishop Hughes, Edgar Allen Poe and Irish immigrant Michael Manning—all members of the village of Fordham during the University’s formative decade. While Hughes was poised to lead the Catholic Church in New York during a time of riots and disease, Poe was seeking fame by writing about caverns of human nature that had long gone unexplored. Manning, who outlived both Poe and Hughes, was simply a poor immigrant from Ireland who made money by cobbling the shoes of the Fordham Jesuits.

“Today, we are at where Poe, Hughes and Manning once were,” said Quinn. “We are suspended between the human city and the holy one, pondering our place, asking the same questions they asked: Whose city is it? Who belongs and who doesn’t? What does God have to do with it? Fordham University is now an intrinsic part of those questions and of this city—physically, psychically and spiritually. It is interwoven into the fabric of New York.”

Fordham’s Jesuit tradition of values-based education, Quinn said, offers a unique perspective from which to ponder the big questions and “create a world in which the possibilities for beauty, knowledge, hope, faith and love belong to the poor and the outsider as much as to the comfortable and the privileged.”

For the Rev. Raymond Schroth, S.J. (FCO ’55), author of Fordham: A History and Memoir, New York’s greatest gift to Fordham has been its impact on the University’s imagination.

“Fordham and the city have often, if not always, accomplished exactly what a liberal arts education is designed to do: They have made it very difficult for us to think small,” he said, echoing the call of Father O’Hare’s inaugural address. “We have been challenged to think like New York.”

A Catholic University for the Capital of the World

In his Fordham and the City lecture titled “From St. John’s College to Fordham: A Catholic University for the Capital of the World,” Msgr. Thomas J. Shelley, associate chair of the Theology Department at Fordham, praised Father O’Hare’s contributions to Catholic higher education.

“For the past 10 years,” Msgr. Shelley said, “Father O’Hare has played a major leadership role in the ongoing dialogue between the Holy See and the American bishops in defining the nature of the Catholic university.”

Throughout his career, in fact, Father O’Hare has been an active voice in Catholic higher education. He is the only person to have served as chairman of both the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities (ACCU) and the Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities. In April 1989, Father O’Hare was part of the 18-member ACCU delegation to the Vatican Congress on Catholic higher education. When the conference concluded, he was elected to a 15-person international committee of bishops and university presidents that returned to Rome that September to review the documents that would be submitted to Pope John Paul II and eventually published under the title Ex Corde Ecclesiae (From the Heart of the Church) in 1990.

Demonstrating his commitment to Fordham’s Catholic intellectual tradition, Father O’Hare fostered several centers devoted to religious dialogue, including the Archbishop Hughes Institute on Religion and Culture, the Office of the University Chaplain and, most recently, the Center for American Catholic Studies (which will occupy the old Duane Library when renovations are completed). In 1988, he established the Laurence J. McGinley Chair in Religion and Society and recruited the Rev. Avery Dulles, S.J., to become its first occupant. In February 2001, nearly 200 members of the Fordham family traveled to Rome, where Dulles became the first American theologian to be elevated to the College of Cardinals. Cardinal Dulles maintains a prodigious speaking schedule in between teaching a graduate theology class and writing and delivering the biannual McGinley lecture. Last spring, he spoke about “True and False Reform in the Catholic Church.”

For four years, students in the Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education have explored the link between faith and healing through the Pastoral Counseling and Spiritual Care program. Three years ago, the School of Law created the Institute on Religion, Law and Lawyer’s Work as a forum for considering the relationship between religious faith and the legal profession. Working in collaboration with the University’s Stein Center for Law and Ethics, the institute provides faith-based resources and connections within the law community. In October 2000, the Graduate School of Social Service’s Bertram M. Beck Institute on Religion and Poverty held its inaugural event, a debate on the issues of welfare reform.

Under Father O’Hare’s leadership, the University has also strengthened its international presence in ways that highlight a commitment to social justice and ethics. The Joseph R. Crowley Program in International Human Rights, established in 1997, raises awareness of human rights problems around the world, and gives students and alumni the opportunity to engage directly in human rights lawyering. More recently, in December 2001, Father O’Hare announced the creation of the International Institute of Humanitarian Affairs, through which the University trains humanitarian aid workers for service in countries in crisis.

Moment of Transition

Fordham has come a long way since the fall of 1984, when Father O’Hare challenged the University community to join “the dialogue with genius and passion that goes on every day in New York City.” As a builder, educator, civic leader and priest, he has been a defining influence on the University these last 19 years. But even as he has reshaped the face of Fordham, transforming it from a good regional commuter school to a “hard-charging institution,” he has kept faith with the University’s defining characteristics—its Catholic identity and Jesuit tradition of education.

“Looking back and looking forward,” Father O’Hare once wrote, “becomes a habit in an institution like a university, which preserves the wisdom of the past and yet is renewed each year by the explosive energy of a new entering class.”

In the coming months, Father O’Hare will return to America magazine, where he served as editor-in-chief from 1975 to 1984, and the University community—faculty, students, administrators and alumni—will prepare for the official inauguration of the Rev. Joseph M. McShane, S.J., the 32nd President of Fordham University.

This moment of transition is a time for reflection and celebration. The accomplishments sketched in these pages—the physical transformation of both the Lincoln Center and Rose Hill campuses, the dramatic increase in the applicant pool, the significant reform of undergraduate education, the completion of the most successful fundraising campaign in University history, the renewed commitment to performing service and promoting justice—are sure signs of vitality. Together, they suggest a vision for the future of Fordham that is even bolder than could have been imagined two decades ago.

Future historians of Fordham and higher education in general will no doubt provide a more detailed analysis of Father O’Hare’s presidency. But from the perspective of June 2003, it seems certain he will hold a prominent and secure place in those histories.

Upon receiving an honorary degree at the School of Law last May, Philippine President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo best expressed the sentiments of the entire University community.

“I pray that God will bless Father O’Hare with abundant grace and yet more years as he steps out of Fordham, not retiring mind you, but moving on to pursue other worthy endeavors,” she said. “He is a true embodiment of the Jesuit ideal of being a man for others. … Fordham will sorely miss him, but his outstanding achievements will endure and make Fordham feel that he is very much around.”