These seniors face the same mental and physical health care needs as people on the outside, experts say, but they’re growing old in a system already strained by the sheer numbers of prisoners, to say nothing of the pressure created by the COVID-19 pandemic. Their plight is the focus of Aging Behind Prison Walls: Studies in Trauma and Resilience (Columbia University Press, 2020), a new book co-authored by Professor of Social Work Tina Maschi, Ph.D., and Keith Morgen, Ph.D., associate professor of psychology at Centenary University.

From Isolation to Solitude

From Isolation to Solitude

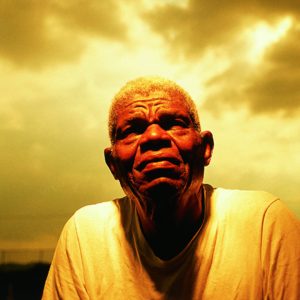

Maschi noted that although the book focuses on aging in prison, it is also a story of humanity. Its data-driven analysis—both quantitative and qualitative—reveals that the men and women behind bars have mustered a resilience that could teach those of us on the outside a thing or two, said Maschi, particularly when most Americans are coping with pandemic isolation.

“Now we’re all in a metaphorical prison, so why don’t we ask the wisdom keepers in prison, what does it mean to take social isolation and view it as solitude?” asked Maschi.

Maschi said the coping strategies used by incarcerated elders include finding meaning in their lives from before, during, and after imprisonment. But society undervalues incarcerated people, so their wealth of knowledge falls mostly on deaf ears. Over the years, Maschi said, she’s come to appreciate older incarcerated people for their unique and informed perspectives.

“One of the elders once said to me, ‘You may have a Ph.D., but I have a direct line to the wisdom only others can read about in your research,’ and I realized he was right,” said Maschi.

Trauma Begets Trauma

Trauma Begets Trauma

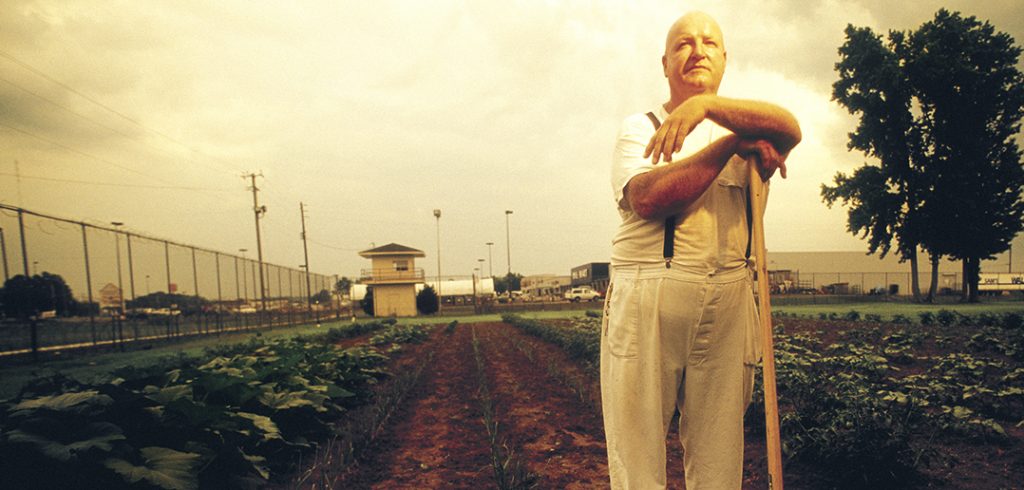

Over the course of 10 years, Maschi interviewed 677 incarcerated people for the Hartford Prison Study under the jurisdiction of the New Jersey Department of Corrections. The research produced multiple journal articles, including a study of some frequently overlooked communities, such as LGBT incarcerated elders. But perhaps her most significant finding was that 70% of the participants experienced three or more traumatic experiences in their lives, including physical and sexual abuse. The ill effects from these experiences linger for many years later, she said. And yet, her research also found that older incarcerated adults who had spent years working through the trauma lived healthier lives into their senior years. They, in turn, passed on the knowledge to younger men and women in prison, of which many were able to make positive changes in their lives.

One young man she calls Joseph credits a prison elder with helping him turn his life around. Joseph had been abused by his parents and a coach. With the help of an elder he was able to gain insight into “what happened to me and what I had to do to get ahold of the monster in control of me,” he tells her in the book. Before that he experienced “a world locked away from all caring feelings and [he]put on a tough exterior.”

Based on the data, Maschi said, “If we give them love instead of suppressing love we know that people have better results.”

Prison as a Metaphor

Prison as a Metaphor

Maschi worked in prisons for 15 years before finding her way to the older adults there. Initially, she researched young prisoners and wanted to understand trauma in their past that paved the way to incarceration. But she also wanted to examine outcomes of being incarcerated over several years, which led her to the older population. In time, she said, she has come to view America’s mass incarceration crisis as analogous to society’s greatest ills.

“The prisons are a metaphor, these are stories of humanity and we need to understand how we got to this point because if don’t want to look at how we got here, we’ll never get out of it,” she said. “And if we don’t do something, we’ll be looking at thousands of people dying, including many chained to beds, and that problem is only going to get bigger and bigger.”

Maschi said that most Americans’ personal and collective beliefs don’t align with the brutality of mass incarceration. She said much of the problem springs from a “fear-based mentality” fostered by the media that distracts people from focusing on the positives that incarcerated people may have to offer.

Caring Justice

Caring Justice

Maschi and Morgen offer concrete proposals—at the community and national policy levels—to address the pressing issues of incarcerated elders. The authors document multiple examples of compassionate programs and interventions that incorporate what they refer to as “caring justice” principles. The approach provides a formalized framework for professionals that integrates “caring” by emphasizing equality, compassion, and authenticity, and “justice” by emphasizing truth, integrity, balance, and ethics. can help everyone examine “how we value, treat, and care for each other.” But the principles are specifically intended to help marginalized individuals and groups, like those with a criminal past, heal and grow. In essence, their recommendations spring from the care that incarcerated elders are already providing in an informal way to younger imprisoned adults

“Caring justice is not coming, it is already here. If you open your eyes you will see it. While the rational view is respected, it should be tempered by the heart and expressed through compassion,” she said. “There’s science behind this; we know from our other research that oppression and hatred often are associated with health and justice disparities. In comparison, a compassionate and authentic approach is most often associated with better health, well-being, and an increased sense of belonging.”

Caring justice is a “heart and head integration” method that Maschi says is best expressed in the spiritual creative writing of an incarcerated older adult known as Mr. J’s Unchained Mind, who is briefly mentioned in the book. Maschi writes that Mr. J’s Unchained Mind enables him to be fully aware of his inner landscape and his relationship to the world. In one paragraph introducing a poem by Mr. J, the authors reference 15 empirical studies that support the importance of “biopsychosocial spiritual medicine” to promote resilience, transcendence, and well-being. That is to say, Mr. J’s faith. He writes:

I was once a Fool but now I’m Wise!

I was once a Fool but now I’m Wise!

I was once Blind but now I See!

I was once Deaf but now I Hear!

I was once Ignorant but now I use Intelligence!

YOU have your Ph.D., but I have Knowledge and Inspiration that comes from a Higher Power, the one and only True GOD!

A Mind is a terrible thing to waste, so is the Soul!