“The biggest lie in this country is that we care about our children. If we cared, there’s no way that things happening to children today would be happening.”

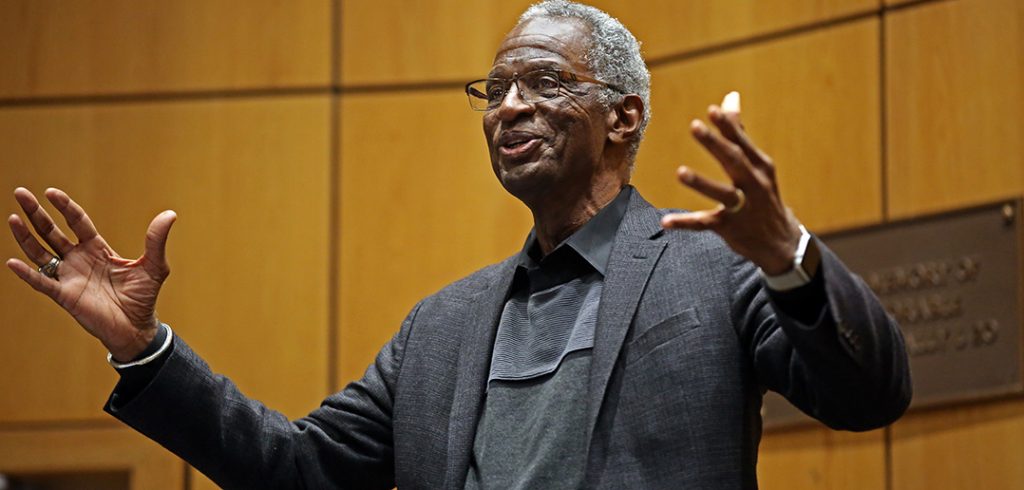

Howard Fuller, Ph.D., a distinguished professor of education at Marquette University, minced few words on Dec. 4 as he delivered the annual Barbara L. Jackson, Ed.D., Lecture at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus.

He offered a full-throated, rousing call for equity and equality in education in the United States. As founder and director of Marquette’s Institute for the Transformation of Learning, he also delivered a blunt warning in his talk, “Educational Options and Systems to Support Equity in Urban Education.”

“I don’t believe that we’ll ever achieve any type of equity or even equality for the children of the families of the disinherited of America,” he said.

“I don’t believe the American body politic writ large cares about these children.”

A measure of justice is possible though, he said, and to get it he advocated for radical changes to public education.

“We need to create new systems of learning opportunities based on a totally different governance and finance structure—one that puts all of this stuff in the interest of students first, allows dollars to follow students, and holds adults accountable for not having our students achieve,” he said.

“This system of learning opportunities must include charter schools, new configurations of the traditional system, schools within schools, public and private partnerships, creative use of technology to allow for multi-sites and, possibly, relationships with home schoolers. Teachers ought to be able to engage in private practice.”

Fuller, the former public school superintendent in Milwaukee, said he is not against public education per se.

“There’s a difference between public education and the systems that deliver it,” he said. “Public education is an idea, it’s the concept that we ought to educate the public. Then we develop these systems to realize that idea.”

And any system can be changed, he noted.

“We must love our children’s loves, hopes, and dreams more than we love the institutional heritage of any system. People say to me, ‘You like charter schools, huh?’ I say, ‘I like anything that works.’”

Fuller noted that emancipation from slavery liberated blacks in the United States, but it did not make them free. Education was the key to freedom, because it is the only escape from poverty available to black children. It has been a struggle to attain it in the face of hostile forces ever since, particularly in the South, where schools for blacks were always inferior.

“Black people in this country [are not]well served when they only have one option,” he said.

But if there will never be equity or equality for all children, why fight? Fuller said he takes inspiration from Derrick Bell’s Faces at the Bottom of a Well (Basic, 1993), in which a woman is asked a similar question during the Civil Rights era. She answers that not to fight is to co-sign on the injustice.

“Irrespective of whether or not I expect [people in power]to do anything, I can’t let them act like this is okay,” Fuller said.