“After a decade of teaching yoga and philosophy at my studio, I realized that I wanted to help people in a more direct way by becoming a mental health professional as well as a yogi,” Robles, GRE ’21, said. “I believe that spirituality—sometimes, but not always in the form of religion—is a central concern for many people.”

‘Throwing Gasoline Onto A Fire, But With Meditation’

As a child, Robles scoffed at the notion of yoga.

“When I was a kid, I turned my nose up at the asana stuff,” Robles said. “It was like glorified gymnastics. I was like, how does that help you be spiritual?”

As he grew older, he became intrigued by meditation and philosophy. When he met his wife Adrea in his late twenties, she introduced him to yoga. In 2004, he took his first yoga class. He was hooked.

“It was like throwing gasoline onto a fire, but with meditation,” Robles said. “I knew this philosophically, but I didn’t experience it [until then].”

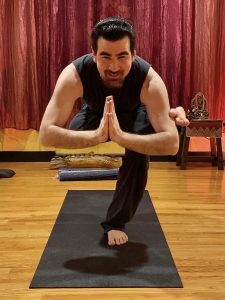

He became a certified yoga teacher and in 2008, opened a small, suburban yoga studio with his wife in Mahopac, New York. At the time, it was a big risk. The 2008 financial crisis had just surfaced, but it was too late to back out of their new business venture—by that point, they had already signed the building lease. But their new studio, Liberation Yoga & Wellness Center, made it through the crisis. This September will mark 12 years that they’ve been open.

Now the studio faces new challenges, thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since it closed on March 16, the Liberation Yoga & Wellness Center has pivoted to online offerings, but Robles and his wife said they plan to open in a limited capacity around July 4.

“Many studios in the Hudson Valley have already closed their doors permanently, but so far, Liberation’s tight-knit community has supported us. While we remain anxious about our future, we hope to be able to continue to serve the area for a long time to come,” he said.

Teaching a Future Generation of Yogis

Throughout the years, Robles said he noticed that some of his clients were mulling over their personal problems at the studio. They approached him after class and asked him for advice on multiple issues: marital drama, questions about spirituality and finding meaning in life, even domestic abuse. But Robles had neither the training nor the certification to answer their questions.

Those encounters helped inspire him to become a mental health professional in addition to being a yogi. In 2018, he became a full-time student at Fordham’s Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education in the pastoral mental health counseling program.

“I wasn’t aware of just how much of a connection there was [between yoga practice and mental health]until I started this program and started talking to a lot of the priests and nuns here … A lot of people end up going to a church not entirely for spiritual guidance, but also for mental health reasons. They’re much more comfortable talking to a priest than to a doctor, psychologist or therapist, sometimes. And I realized that that’s exactly what’s happening in my yoga studio,” Robles said. “It gathers people who are looking for healing, and frequently, what they’re needing is more than a yoga teacher or priest.”

He said his Fordham lessons—in particular, an ethics course and a trauma elective—have changed the way he views yoga.

For years, it was a commonplace practice—not only in his studio, but places worldwide—for teachers to touch a client’s body and correct their posture without asking for permission. After becoming more aware of trauma and how physical touch can trigger a traumatic reaction, Robles introduced a new method for clients to communicate whether they wanted a “physical assist” or vocal directions: wooden chips that say “Yes, assist” on one side and “Please refrain” on the other.

“It’s something that I’m only even now, through this program, becoming more aware of—just the sheer prevalence of trauma in the yoga room. Once you start to see it, and you’re trained to look for it, it’s everywhere,” said Robles, who introduced the new technique to his clients this past winter. “With COVID-19, the issues of touch may be a moot point for a long time, but the shift of thinking to being more mindful and respectful of differences in how touch and personal space is experienced will remain. In fact, such considerations may become even more important in the long run due to the pandemic.”

Ultimately, Robles wants to become a full-time mental health counselor, while continuing to work with clients at the Liberation Yoga & Wellness Center with his wife.

“I believe my experiences as a yoga teacher will greatly inform my counseling, and I hope that once I’m fully licensed, I will be able to offer some expertise to the community of yoga teachers in the form of workshops or continuing education,” he said.

That includes teaching yogis-in-training about trauma-informed yoga practices—something he himself wasn’t trained on, he said.

“The real thing that’s going to benefit my yoga community is additional training for my staff and teachers on how to handle those situations when they arise with more grace and certainty … really knowing what the resources are and learning how to recognize certain things,” said Robles, who will intern at a trauma-specialized counseling center next year.

In the future, he said, he sees yoga teachers taking spirituality to a new level.

“As a friend of mine who’s a Unitarian minister says,” said Robles, “Yoga teachers are the new clergy.”