College students are no strangers to stress; they worry about everything from their exams to relationships to prospective careers. But what about sociopolitical events like the U.S. presidential election?

That question was at the forefront of a new study, “Young adults’ psychological and physiological reactions to the 2016 U.S. presidential election,” published in this month’s issue of Psychoneuroendocrinology and co-authored by Lindsay Till Hoyt, Ph.D., assistant professor of psychology at Fordham.

Hoyt and researchers at University of Arizona and Arizona State University examined the emotions and stress hormone levels (measured by diurnal cortisol), of 286 young adults from November 6 through November 10.

According to Hoyt, who specializes in stress biology, health disparities, and positive youth development, the study complements the American Psychological Association’s (APA) 2017 report, “Stress in America: The State of Our Nation,” which found that 63 percent of American cited the future of the nation as a significant source of their stress.

An Unequal Distribution of Stress

“The big takeaway of the APA report was that the election represented a time of heightened stress for the country,” said Hoyt. “However, our study suggests that stress is unequally distributed. As someone who studies health disparities, I’m interested in how these larger social and political events have distinct effects on different groups of people and how that might contribute to long-term social or health disparities.”

For their study, Hoyt and her co-authors focused on young adults between the ages of 18 to 25 who were based at a mid-sized private university in New York and a public university in Arizona.

Before the study, the 286 participants took a survey about their mental and physical health, attitudes toward the different candidates, political orientation, who they were planning to vote for, and their families’ political orientation. Then, researchers asked them to document their daily attitudes, feelings, and behavior across five days: two days before the election, on election night, and two days after the election.

According to Hoyt, it was important to couple these self-report methods with the participants’ salivary cortisol levels, which were gathered three times per day over five consecutive days.

“When you’re measuring something like mood, you’re relying on people’s self-assessments,” said Hoyt, “but sometimes there are a lot of things going on in our brains that are interfering with how we may report feeling.”

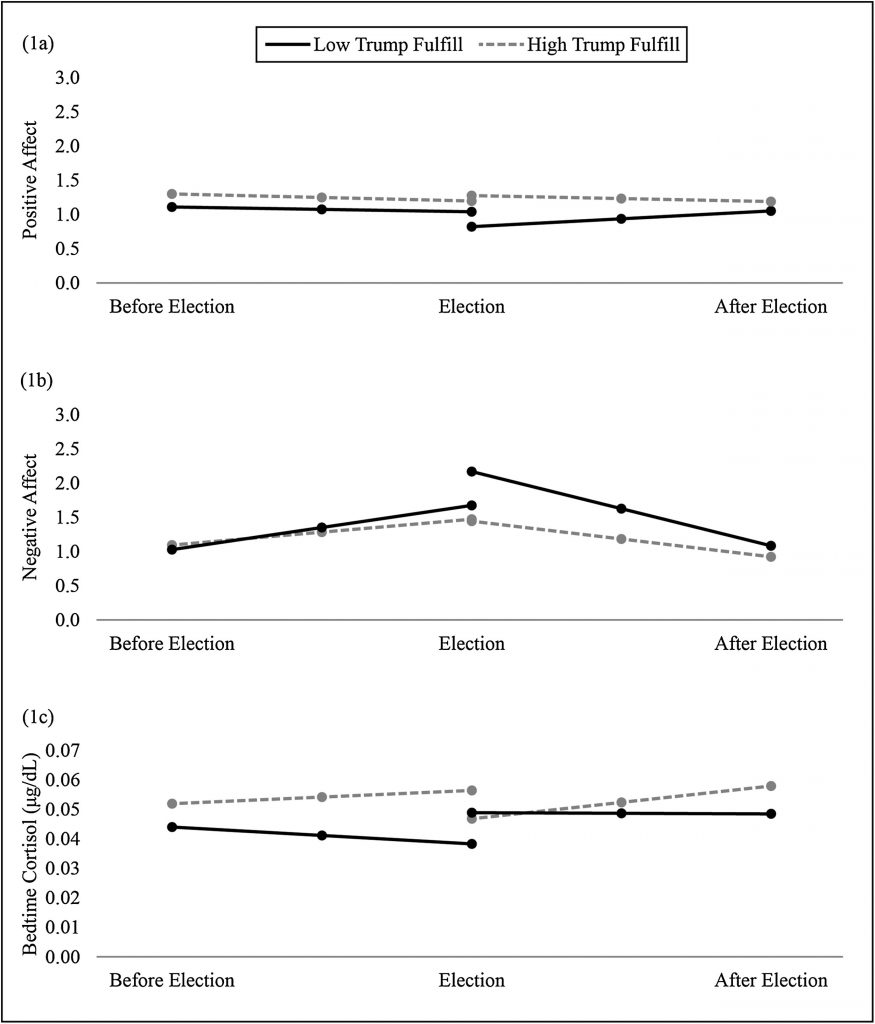

The researchers found that overall, participants had high levels of negative emotions before the election and increasing negative emotions on election night. Though most participants experienced a decrease in negative emotions after the election, or a “recovery” in their moods, Hoyt said physiological responses to the election were partially dependent on gender, ethnicity, race, and other factors.

For example, participants who self-identified as a member of an ethnic/racial minority (ER) generally reported an increase in negative emotions and a marginal increase in bedtime cortisol levels leading up to the election, with no post-election recovery. White young adults had an increase in negative emotions before the election, a decrease in negative emotions after election night, and a distinct physiological response across the week: marginal drop in bedtime cortisol before the election and a significant increase after the election.

“This may suggest a delayed response to the election results among white young adults in this sample—to the extent that they were more surprised by Trump’s win than their ER-minority peers,” she said.

One thing that made the election different, Hoyt said, was that Hillary Clinton was the first female presidential candidate of a major U.S. political party.

The research findings showed that men, on average, experienced a decrease in positive emotions leading up to the election and a slight increase in positive emotions, as well as a decrease in bedtime cortisol, on election night. Meanwhile, women experienced a decrease in positive emotions on election night without a post-election recovery.

“We have to think about these results in context. For example, pretty much every major polling organization was expecting a Clinton victory,” said Hoyt. “And previous research about men’s attitude toward women in authority roles suggests that men may have had a more positive reaction to the maintenance of the patriarchal dominance in the U.S. compared to women.”

Still, Hoyt noted that there are limitations to the study. For example, the young adults who participated in the study were in college and a majority of them were white and middle-to-upper class.

For future studies, she plans to examine the long-term impacts of political events on a larger sample of traditionally marginalized groups, including low-income groups, LGBTQ individuals, women, and immigrants.

“Our hope is that this study will provide the fuel for a larger study where we can examine intersectionality,” she said.

The article “Young adults’ psychological and physiological reactions to the 2016 U.S. presidential election,” is co-authored by Lindsay Till Hoyt, PhD, Katharine H. Zeiders, PhD, Natasha Chaku, MA, Russel B. Toomy, PhD, and Rajni L. Nair, PhD. It appears in Psychoneuroendocrinology (2018), published by Elsevier.