In 1946 Charles and Ray Eames created a chair that Time magazine would describe as the “greatest chair design of the 20th century.”

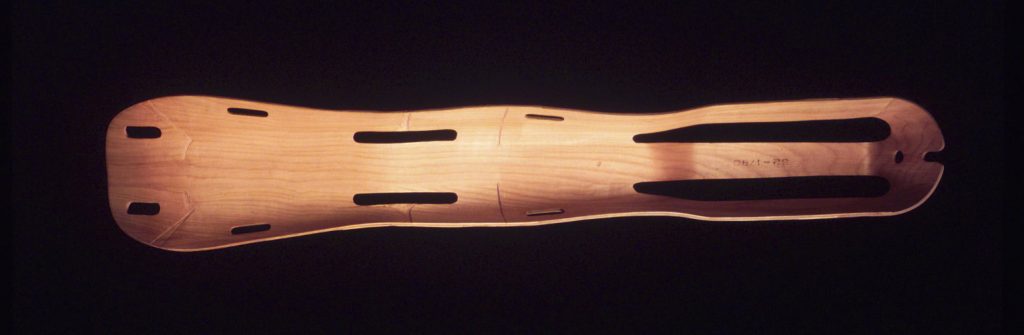

The molded plywood “Lounge Chair Wood” had very practical roots, according to scholars, in that it was inspired by a leg splint the couple designed to help heal injured soldiers during World War II.

Claire Fields, FCLC ’16, takes the splint/chair connection a step further. In the latest issue of the Fordham Undergraduate Research Journal, the recent graduate asserts that the healing relationship between the body and the object in the case of the splint can also be applied to the relationship between the body and object as it relates to the chair.

In other words, the chair is healing.

“There’s been a number of scholars who say that the chair’s design comes out of the splint, but the observation that the chair was simplified to benefit the body of the person sitting in it has been overlooked,” said Fields, who majored in art history. “Rather than focus on the aesthetic value of the simplified chair form, I focus on its orthopedic value.”

Fields, who owns one of the chairs, said that the idea came to her from sitting in it.

“It’s hard, it’s plywood, and yet it’s comfortable,” she said.

Fields took a highly theoretical approach to make her argument, namely the architectural prosthetic theory.

“The idea is that furniture and man-made things supplement our inefficiencies, like a prosthesis would,” said Fields.

The theory, developed by Mark Wigley, PhD, former dean of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Preservation and Planning, uses architecture and design as an example; Fields uses furniture. Yet, while the concept might seem abstract, the reality is concrete.

The theory, developed by Mark Wigley, PhD, former dean of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Preservation and Planning, uses architecture and design as an example; Fields uses furniture. Yet, while the concept might seem abstract, the reality is concrete.

“It really comes down to a sitting experience,” she said.

After presenting her research to fellow classmates and her adviser, Nina Rowe, PhD, Fields asked everyone to sit in the chair. She said the point was to show that many, if not all, body types found comfort in the chair, which drove home yet another aspect of her research—the role of mass production.

“It goes back the leg splint, because there were 150,000 splints made that healed many different body types,” said Fields. “The idea is that something that’s mass produced can fit each body type—even though there are millions made.”

Beyond the chair, Fields said the project made her think about what is considered great art, especially since some of the world’s greatest works of art are a mere half-hour walk from campus at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on Fifth Avenue.

“We had all these incredible artworks at our fingertips and these one of a kind objects are glorified, but there are things that are made in the thousands—the millions even—that can be just as special to so many different people.”