When we stare into the heavens, are we moved more by religious epiphany or scientific wonder?

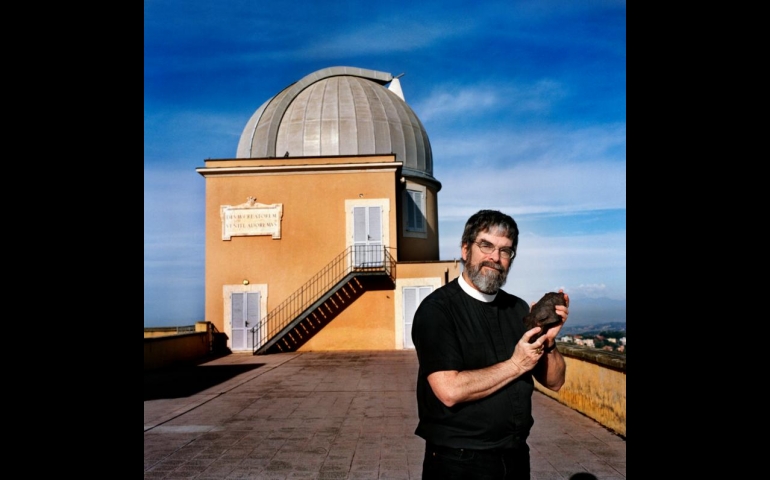

For Guy Consolmagno, S.J., it has been both, perhaps in equal doses. In a talk on the Fordham campus on Feb. 26, Brother Consolmagno, the director of the Vatican Observatory, said that religion and science enjoy a long partnership in humans’ endeavor to understand the world in which they live.

“Studying science is an act of worship,” said Brother Consolmagno, a graduate of MIT, former Peace Corps volunteer, author, and research astronomer. “You have to have faith in the questions you are asking.”

Delivering the John C. and Jeanette D. Walton Lecture in Science, Philosophy, and Religion, Brother Consolmagno drew parallels between an unlikely pair: Galileo, a Renaissance man who created the telescope and changed science forever, and Pope Francis, whose concern for climate change’s effects on the world’s poor is aimed at reinvigorating the Catholic mission.

“Galileo Would Have Been On The Colbert Show”

Had he been born in the 20th century rather than the 16th, Galileo would have been world-renown, “a media star … just like Carl Sagan,” said Brother Consolmagno. “[He] would have been on The Colbert Show, the Tonight Show.” Although Galileo’s notoriety landed him in some trouble with the church in his day, said Brother Consolmagno, his important scientific discoveries set in motion a revolution on how scientists make assumptions about the universe. It moved science from the Golden Age of celebrating book knowledge of the past, to the scientific revolution of seeking knowledge for the future.

“Galileo was special because he had the telescope and was able to see and understand what he was seeing . . . the moon’s craters . . . the Orion Nebula,” said Brother Consolmagno. “And he was seeing things that were not in any book.”

“He understood why it mattered, and he knew it was important to tell the world.”

Laudato Si’: What Pope Francis Sees

Brother Consolmagno called the pope’s encyclical, Laudato Si’, an entreaty that doesn’t settle scientific questions but draws on today’s scientific research to conclude “the environment is reaching a breaking point that will cause a change in humanity that cannot be fixed by technology.” Francis says these ecological problems are symptoms of much deeper social justice issues, “symptoms that come out of personal sins” and our detachment from God.

“The pope is [offering]new assumptions, just as Galileo saw a new set of assumptions in how the universe works,” he said.

The pope’s call to action, said Brother Consolmagno, is for human beings to develop a new set of ethics, “a new idea of what is wrong” in the human relationship to nature and human ecology. Nature, like the human, is a creation of God; therefore it is mankind’s to care for like a sibling, not to own.

Nor are humans gods who can fix ecological degradation through technology, he said. Technology advances over time, but human ethics tend to waver: a technologically-advanced society may not necessarily solve the earth’s problems.

“Ask yourself who had better ethics: Nazi Germany? Or Socrates?”

By calling for a change in our humanity, the pope’s encyclical does much to demonstrate why science needs faith, said Brother Consolmagno.

“How do we know what change will be for the better? Ultimately, the Jesuit answer is, if it brings us—human beings who will never be God—closer to God.”