An exhibit at Fordham is honoring the lives of migrants who died while trying to make it to the United States.

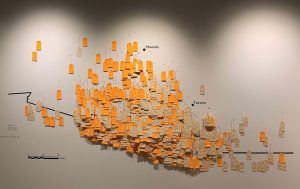

Hostile Terrain 94, an art installation that aims to call attention to the ongoing humanitarian crisis at the southern border, will debut on Thursday, Nov. 4, in the Lowenstein Center’s Lipani Gallery.

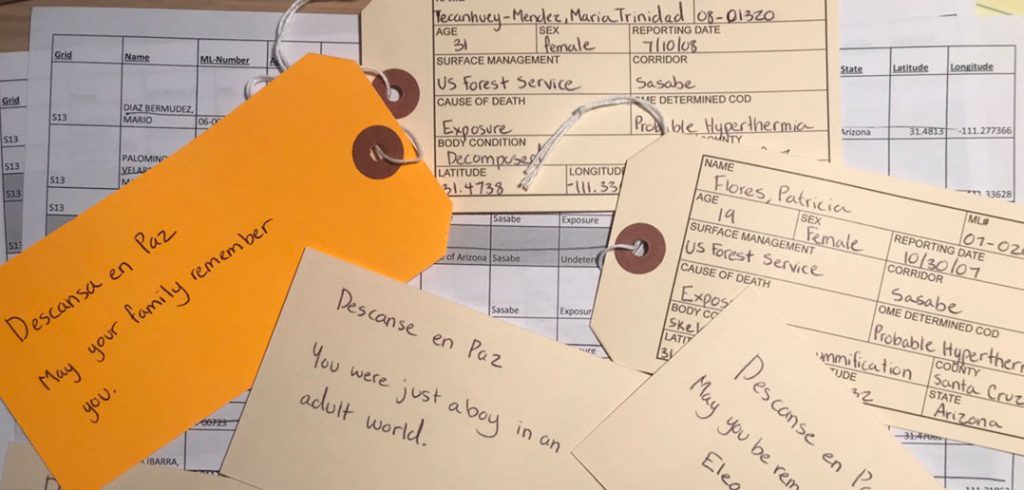

Composed of 3,205 handwritten toe tags that represent migrants who have died trying to cross the Sonoran Desert of Arizona between the mid-1990s and 2019, the ongoing project includes participants from several communities—including Fordham.

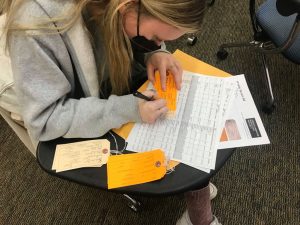

Members of the Fordham community have been recruited in classes and at table, sessions to fill out the tags, some of which contain personal information about those who died. Information about each of the migrants was collected by a nonprofit group called the Undocumented Migration Project and provided to groups that participate.

Carey Kasten, Ph.D., associate professor of Spanish, spearheaded the effort, which was originally timed around the November 2020 elections. Kasten opted to wait until after the pandemic because in-person participation was key to the project, which was funded by a $10,000 dean’s challenge grant and support from the offices of the Chief Diversity Officer and the Office of Mission Integration and Ministry. In January, the installation will move to the Rose Hill campus offices of the Center for Community Engaged Learning.

“It’s great because you get people coming to these sessions because they know about them, but you can also stop people and talk to them, which is what I really like because you have an interaction with someone who may not initially be interested in this, and then they take a moment to enter into this space where they’re thinking about border policies from a personal standpoint,” said Kasten, who has also recruited participants from outside groups such as the Hebrew Tabernacle Congregation in Washington Heights and Ellis Preparatory School in the Bronx.

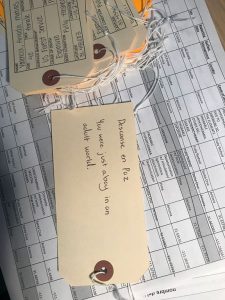

“That encounter with someone’s life is intense, and I think it’s surprising to people, the emotions that come up and the experience of writing down someone’s name, or even an unidentified body.”

The exhibit is part of a series of pop-up exhibits that the Undocumented Migration Project has promoted at 150 locations around the world. The tally begins with migrants who attempted to cross the border in 1994 because that was the year that the United States Border Patrol formally implemented an enforcement strategy known as “Prevention Through Deterrence.” The idea was that discouraging undocumented migrants from attempting to cross the U.S./Mexico border near ports of entry would force them to attempt to cross through areas such as the Sonoran Desert, and the treacherous natural environment would act as a deterrent.

Instead, more than 6 million people have attempted to migrate through the desert since 2000, and at least 3,200 people have died while attempting the journey, largely from dehydration and hyperthermia.

At Fordham, Kasten has reached out to fellow faculty to ask if their students will participate. Yves Andradas and Tzipporah Goins, first-year students enrolled in an honors natural sciences class taught by Jason Morris, Ph.D., professor of biology, recently filled out toe tags as part of their classwork. Morris incorporated discussions about the effects of hyperthermia on the human body, and the geologic patterns behind the creation of deserts.

Andradas, who hails from East Flatbush, Brooklyn, and plans to major in philosophy, said he was generally aware of what is happening on the border, but has a better appreciation for the severity of the problem now. Still, watching videos and reading articles about it didn’t really prepare him for the day he and his 18 classmates filled out tags.

“The activity was only about 15 minutes, but it felt so much longer,” he said.

“There was a very strange silence in the room. I don’t have a problem with silence, but in this situation, the silence was very purposeful. People knew not to start a background chat.”

Goins, a York, Pennsylvania, resident who is planning to major in film and English, was struck by how many tags in the envelope she was given were for bodies that were never identified when they were found in 2003 and 2004, when she was just 2 years old. One of Goins’ best friends is an undocumented immigrant and is very open about her status, so immigration is not new to her. But as a daughter of an immigrant herself, she said that filling out the tags still hit home.

“I had to restart twice, and I was so focused on the fact that I made a mistake, I had to take a step back and, tell myself, ‘It’s ok that you made a mistake,’” she said.

“Focus on the fact that you’re writing about someone who has actually died. This is someone else’s name, and this is their life, and this is their story.”

She also couldn’t help but take note of her ability to participate in the project from the safety and comfort of the campus.

“I definitely felt very privileged to be able to do this. For us, it can be just a project,” she said. “I wish I had filled out more.”

Kasten said they’ve finished about a third of the tags and is hopeful the rest will be done by mid-November. Anyone who is interested in helping can lend a hand, she said. The exhibit will be on view through Nov. 29.

“3,205 doesn’t seem that big, but I can tell you, I’ve touched each one of these tags as we close out the folder, and the act of collating that many toe tags does make you realize the gravity of that number,” she said.

It’s important to have conversations about this topic, she said, because there are many misconceptions about what’s happening on the ground.

“I’ve had people who’ve been much more touched than they thought they would be, or they’ve been confused as to why this is the way it is,” she said.

“During the Trump presidency, lot of people learned about migration in ways they hadn’t before.

They think this is a new policy, but it’s not; it started in 1994. This is not a partisan issue. It’s something that has been happening systematically for a really long time.”