Rather, the country’s swollen prison populations stem from a whole host of social causes—class, poverty, race, family breakdown, mental illness—combined with “an overly punitive criminal justice apparatus,” said Anthony Bradley, Ph.D., GSAS ’13, in a recent appearance at the Rose Hill campus.

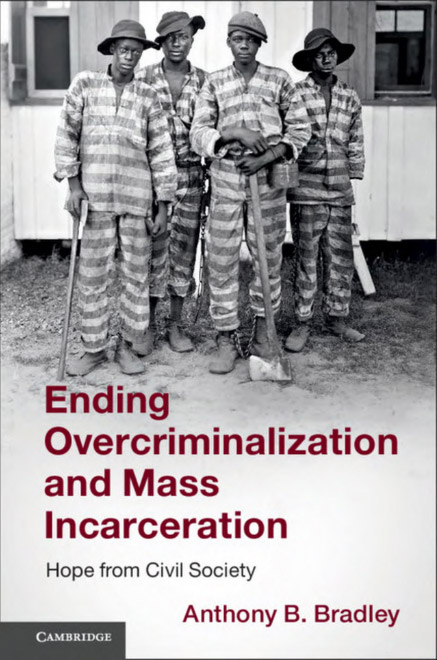

In his book, Ending Overcriminalization and Mass Incarceration: Hope from Civil Society (Cambridge University Press, 2018), he argues that the prison problem in America won’t be solved by policy changes alone. It also requires a comprehensive, long-term approach to safeguarding the well-being of people who are at a higher risk of getting in trouble with the law—and we can all play a part, he said.

In his book, Ending Overcriminalization and Mass Incarceration: Hope from Civil Society (Cambridge University Press, 2018), he argues that the prison problem in America won’t be solved by policy changes alone. It also requires a comprehensive, long-term approach to safeguarding the well-being of people who are at a higher risk of getting in trouble with the law—and we can all play a part, he said.

“This is largely an issue about who we decide has human dignity and who does not,” said Bradley, professor of religious studies and director of the Center for the Study of Human Flourishing at the King’s College in Manhattan.

Causes of Mass Incarceration

The book had its beginnings in a class he took while earning a master’s degree in ethics and society at Fordham. He was “blown away,” he said, after learning about the links between young children developing post-traumatic stress disorder and ending up in the juvenile justice system later on.

“I realized that we’re not just locking up bad kids, we’re locking up hurt kids. It completely changed the course of my career,” he said during his Nov. 7 visit to Fordham, where he addressed students–including many in the ethics and society master’s program–during a talk sponsored by the Center for Ethics Education.

He got another push in this new research direction when he heard the argument that the war on drugs was driving mass incarceration in the U.S. “My research methods antennae popped up,” he said.

Digging into the data, he found that about 90 percent of all inmates are in state prisons, and of those, only 17 percent are drug offenders. In part because of a focus on federal prison data, “we get the story wrong,” he said. “If we don’t get the story right, we’ll get the solutions and interventions wrong.”

Part of that story, he said, is society’s views toward the poor. “Here’s a tough social fact in this country: We resent poor people in America regardless of their race,” he said. “We’ve used the criminal justice system to remove them, the poor, from civil society.”

“Mass incarceration is largely an anthropological problem rather than simply a political problem,” he said.

The label of criminal “rabble” has fallen on various groups throughout U.S. history—on Western European immigrants at first, then on black men in the latter 20th century, he said.

Today, imprisonment rates for African-American men in urban areas is declining. But “there’s a dramatic spike in the incarceration of women, and scholars are not quite sure exactly why that is,” he said.

And rural imprisonment rates are also on the rise. “Some scholars argue that the new ‘rabble’ are lower-class white people,” Bradley said.

Everyone breaks laws, but poor people are unfairly targeted by the justice system because they can’t afford a quality defense, and instead have to rely on public defenders who have excessive caseloads and inadequate resources, he said. “People who enter the criminal justice system are overwhelmingly poor,” and their poverty is compounded when their prison records create a barrier to employment, he said.

Caring for the Whole Person

The federal government enacted the First Step Act in December to reform criminal justice and reduce prison crowding, following on many state governments’ legislative efforts over the past decade. In his talk, however, Bradley highlighted changes that are needed beyond the policy realm.

Emphasizing offenders’ traumas and mental health concerns, he called for “upstream” efforts to help children before they wind up in trouble with police and the courts.

“The problem is we have hurting children, and as long as we have hurting children we’re going to have violent children,” he said. “We need to invite more players to the table. Yes, we need lawyers; yes, we need judges. … We also need coaches and teachers and business owners and cousins and aunts and uncles and community nonprofit leaders to offer the sorts of interventions that address the whole person.”

“This is about caring about people—real people with stories and histories and past and futures, and relationships, and families and friends,” he said, calling for solutions that touch on the emotional, social, psychological, and moral realms.

“Policy changes are not going to be enough,” he said. “We have to think about interventions that impact the totality of what it means to be truly human. It requires a holistic approach that invites multiple disciplines to the table. Whatever your major is, whatever discipline you’re studying … you too can have a role to play in reducing these numbers of men and women who are incarcerated.”

He said he learned the importance of combining disciplines at Fordham, in the master’s program in ethics and society, which mixes ethics, philosophy, and theology courses with courses in social and natural sciences, law, social service, and other fields.

“I’d like to invite you all to think about the ways in which your particular area, whatever that is … might fit into the narrative of addressing the needs of the whole person to bring a solution to a problem that I believe your generation can actually solve,” he said to the students.

He said the students may want to consider interning with Community Connections for Youth, a Bronx agency that provides alternatives to incarceration for at-risk young people. “What do they need? They need people to care for them,” he said. “They need people to be there. They need people to help them navigate the legal system.”

He emphasized the benefits of simply getting involved in a struggling person’s life, giving the example of his mother, who spent 30 years working in public schools in inner-city Atlanta. She’s now in her 70s, but her former elementary school students—who are in their early 50s—still come by her house.

“She’s still involved in helping one of them who has severe learning disabilities pay his bills, take care of his apartment, and things like that,” Bradley said. “That’s because she personally got involved in his story. Not on a six-month, one-year basis, but sort of a lifetime thing.

“His life has been changed because one teacher got involved in it,” he said. “I wonder what would happen if we all got involved with one person.”