In memorializing Fordham’s late provost, Stephen Freedman, several speakers at a Sept. 6 Service of Remembrance struck parallel themes about their friend, mentor, colleague, husband, and dad, who died suddenly on July 2 at the age of 68.

Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, added to that list of roles, calling Freedman a biologist, polymath, unshakable optimist, Jewish scholar with an Ignatian heart, United Airlines’ best customer, New Yorker by adoption, defender of the poor, champion of liberal arts, Fordham Ram, and “hugger—hugger of donors, hugger of students, hugger of anyone within hugging distance.”

“Stephen was the nearly perfect citizen of the University and of every university that was blessed by his presence in the course of his long career,” said Father McShane. “We were ennobled by his presence, challenged by his dreams, guided by his wisdom, consoled by his love, and enriched beyond measure by his friendship.”

Choosing Life

Eve Keller, Ph.D., president of the Fordham Faculty Senate, said that she had sat across the table from Freedman in boardrooms and restaurants, where he mastered his roles as both mediator and friend.

Keller highlighted Freedman’s Jewish faith by quoting a portion of the Torah from Nitzavim, Deuteronomy: “I call heaven and earth to witness against you today, that I have set before you life and death, blessing and curse. Therefore choose life, that you and your offspring may live—so that you may live, you and your seed.”

She noted that rabbinic commentaries typically contextualize the verse as a summing up of preceding texts on rewards and punishments for the Israelites. But Keller chose to focus on particular words in the concluding command: “choose life so you may live.”

“[It] draws my attention away from context and prompts me to read the phrase not as an admonition about obedience, but as an exhortation about choice,” she said. “Choose life, do not merely live it, because to in order to live, in order to really live, you need to actively and consciously engage life in all its pulsing frenetic fullness.”

She then paused to compose herself before continuing.

“Stephen Freedman opted for life,” she said. “Though Lord knows we did our best to beat him up, even at times to beat him down, but Stephen was always on the side of life, always up for another conversation, another hug, another bottle of rather good wine. ‘Tell me about you. Tell me how you are.’”

A Yiddish-Speaking Ignatian

Freedman’s journey from scrawny Yiddish-speaking Canadian to nattily dressed leader at a Jesuit institution was noted by many as point of pride for both him and the University. It was a cross-cultural adventure that was recalled, in part, by Rabbi Eleanor G. Smith, M.D., Freedman’s former rabbi who led the service in the University Church. Smith first met Freedman when she was an aspiring doctor at Loyola University in Chicago and he was dean of Mundelein College there.

“He introduced me to every single nun on campus,” she said of her friend, who spent four decades of his career at Jesuit universities.

According to John Pelissero, Ph.D., provost emeritus at Loyola Chicago, he made an impression on 99-year-old Sister Jean Dolores Smith, the iconic chaplain for Loyola’s men’s basketball team and assistant dean at the college. On starting his position as dean, he asked her if there were any issues that needed his attention. She gave him a “scouting report,” a piece of paper with 17 issues that needed to be addressed. A year later he returned a crumpled piece of paper with all 17 issues checked off.

“Stephen always respected my good advice,” Sister Jean recently told Pelissero.

Rabbi Smith recalled a trip she took with Freedman to meet a Jesuit M.D. who lived an hour’s drive from Loyola’s campus. Once there, a lunch commenced, with deep discussions on faith and medicine.

“Then we drove an hour back, like that was his job,” she said. “He held my call to medicine with me and lovingly shepherded me through his neck of the woods and is partly responsible for that dream coming to life.”

Conversations

“He led by conversation, not by memorandum,” said Eva Badowska, Ph.D., dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

She too saw Freedman as a mentor, someone who encouraged her journey to becoming dean not with pep talks, but with probing questions that made her zero in on her goal.

“Are you sure Eva, are you really sure?” he’d ask.

“How this question always undid me,” she said, though she added that it also reassured her. “He didn’t so much care that the next step should be perfectly right; he cared that I should have thought about it. He wanted, as he said, ‘to see fire in the belly,’ but he had no patience for unquestioned self-confidence or unanalyzed certainty.”

Badowska spoke of a University photo of Freedman on the steps of Keating presiding over commencement ceremonies. In the photo, a smidge of pink material could be seen between a crisp shirt collar and his blue academic robes. It was a Hawaiian lei, she said.

“What was this Jewish provost at a Jesuit Catholic university doing wearing a lei under his academic regalia?” she asked. “And he said, ‘This is to remind me this is a happy day.’”

He loved the pomp and circumstance of academic life, she said, but needed to remind himself of the joy of the occasion. Accordingly, many of the deans and dignitaries on the altar at the service wore leis too. She said Freedman always dreamed about relaxing on a Hawaiian beach, though in truth, the notion was very much out of character.

“He was just about the last person who could sit quietly on a beach relaxing with fruity tropical drinks—and anyway he was into red wine,” she said.

Restless Spirit

Indeed, Freedman’s son, Zachary Freedman, Ph.D., assistant professor of plant science at West Virginia University, recalled physically active rather than restful family vacations. On ski trips, he and his father were the first on the slopes when the lifts opened, skiing up and down the mountain all day until the lifts stopped running, “when it felt like your legs were going to fall off.”

“Lunch breaks were for the weak,” said Zachary.

Zachary said his father was a “first-generation college student, an immigrant, an outsider, and an American success story.” He was born April 7, 1950, to Sam and Sylvia Freedman of Montreal, Quebec. Freedman’s own father was an orphan-turned-Golden Glove boxer and his mother was the daughter of Polish immigrants. His first language was Yiddish.

The family owned a gas station and repair shop where they put in very long hours. Freedman started pumping gas when he was 13. Zachary said this was where his father developed his work ethic.

Freedman met his wife, Eileen Shore, at Loyola College in Montreal (now Concordia University), where they were both biology majors. The two became “best friends for 50 years and married for 44,” Zachary said. He said that his father often said that his most joyous days were when Zachary and his brother Noah were born. His darkest day was when his mother, “his center of gravity,” died suddenly at the age of 60.

“The journey of grieving his mom’s death solidified in him a sense that our time on earth is finite and too short, and that life is precious and should be experienced and enjoyed to the fullest extent,” said Zachary.

“He did all the things great dads do, red light green light, duck duck goose,” he said. There were basketball games, and “super fun days” that once included trips to Chucky Cheese’s and WWF and eventually evolved into adult golf outings and Cubs games. And then there was the final “super fun week” in Beijing, China, where Zachary and Noah joined their dad on a work trip, where he was laying the groundwork for Fordham’s international strategy.

“He was so proud to show us around that ancient city that he had gotten to know and love over the years,” he said.

“If there’s any comfort to be sought in my dad’s premature death, it’s that he most definitely lived life to the fullest, he gave it everything that he had,” he said. “In doing so, my dad naturally and effortlessly embodied several Jesuit values: cura personalis, care of the whole person; women and men for others, my dad was always ready and eager to help another.

“But I would argue most of all my dad embodied magis, or simply more, striving for better, striving for excellence, no matter what.”

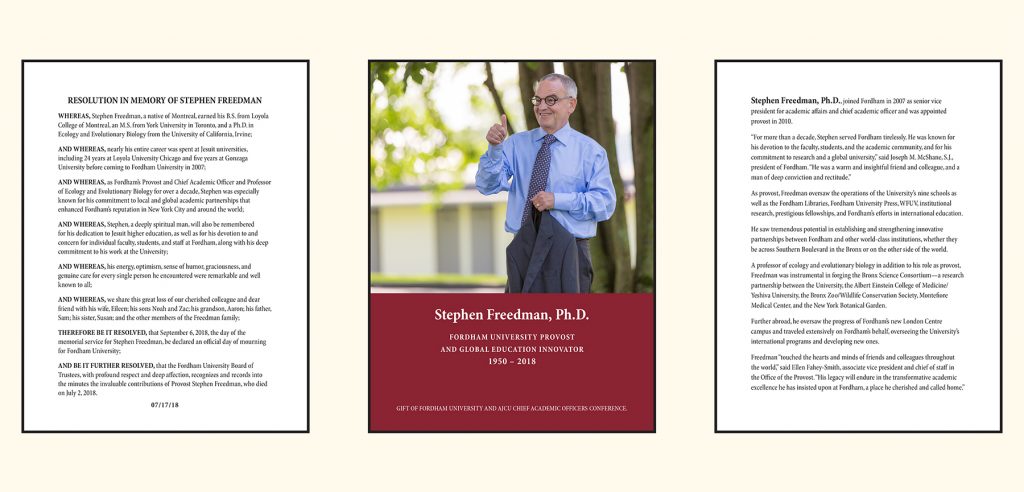

Preceding the service, members of the Freedman family and several members of the Board of Trustees dedicated the Freedman Conference Room at Cunniffe House. Below is the memorial plaque.