“Oscar Wilde was the first philosopher of glam,” said Reynolds. “And there’s a legacy that’s a lot richer than most people think. About 50 percent of the punks were glam diehards.”

Reynolds, author of Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and Its Legacy, from the Seventies to the Twenty-First Century (Harper Collins, 2016) came to Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus on Oct. 17 to discuss the book with an audience of historians and musicologists.

Reynolds said he extensively “read around the subject,” including Thomas Carlyle’s 1840 tome, On Heros, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History. He researched academic articles on decadence and the history of camp, and thumbed through the yellowing pages of Melody Maker, the British music weekly that ceased publication in 1999.

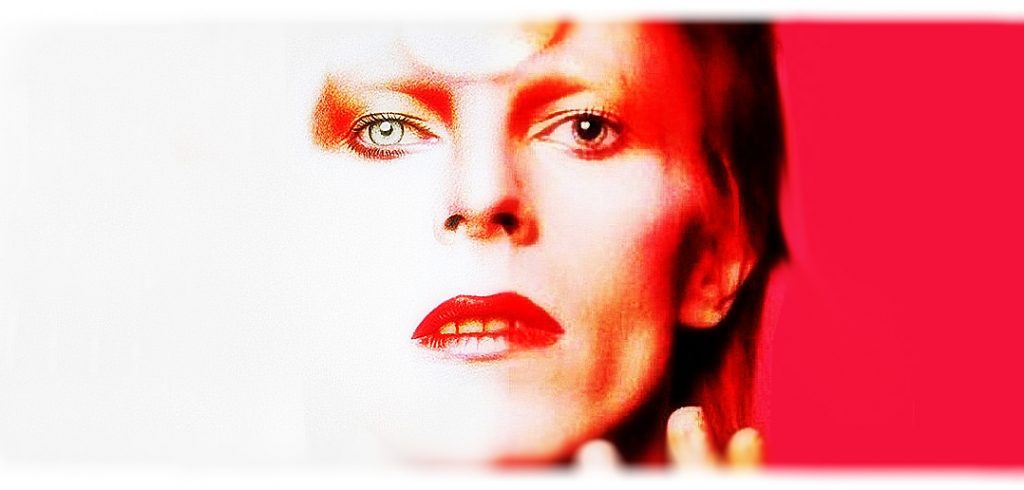

Glam Rock performers were mostly heterosexual men, he said. From David Bowie to Roxy Music to Marc Bolan to Alice Cooper, the subversive use of androgyny was counterbalanced by a hard-charging sound that beckoned the rock idol “back to the 1970s,” after the staid performances of the late 1960s.

“Theatricality is a big part of glam, and that hadn’t been part of rock, especially in the late sixties when there wasn’t much to look at because it was just about the music,” he said. “In reaction to that, people like David Bowie and Alice Cooper brought in all the accoutrements of show biz: the props, the costumes, and choreographed routines with dancers on stage—all the things of Broadway became part of rock.”

“Theatricality is a big part of glam, and that hadn’t been part of rock, especially in the late sixties when there wasn’t much to look at because it was just about the music,” he said. “In reaction to that, people like David Bowie and Alice Cooper brought in all the accoutrements of show biz: the props, the costumes, and choreographed routines with dancers on stage—all the things of Broadway became part of rock.”

Reynolds said that despite its avant-garde reputation, glam rock music actually has its roots in the pop music of the 1950s (albeit incorporating innovations of the late 1960s, like Jimi Hendrix’s layering and stacking of guitar parts).

“What defines glam musically is a reaction against acid rock; it’s back to more simple structures of the 1950s . . . that kind of punchiness and focus,” he said. “But glam also sleuths through all the recording advances of the late 1960s, when rock ‘n’ roll records sound much bigger, tougher, louder, and fatter than in the fifties.”

But glam was much more than the music, he said. Record executives were hungry to recreate the money-generating rock icon that had been lost in the sixties. For someone like Bowie, that meant nearly eight years of trying on different personas—something that started out as an effort to ride the latest popular wave but ended up becoming a key part of his image.

“It becomes his way of differentiating himself at a time when the career trajectory of artists like Neil Young evolved very slowly,” he said. “Bowie invented jumping from style to style, and now that’s a common strategy that loads of artists use.”

Asked whether a glam movement would happen today, Reynolds said that it already has—with women like Lady Gaga and Kesha. In fact, it never really left: British gay men kept alive the movement in the 1980s, with Boy George and Pete Burns of Dead or Alive, to name a few. He said that many women from the 1980s, such as Annie Lennox and Siouxsie Sioux of Siouxsie and the Banshees, could also lay claim to the glam mantle.

An audience member asked Reynolds why he chose “Shock and Awe” for his title, a phrase that gained fame during the second Gulf War (though Reynolds noted that the concept originated with 19th-century German military theorist Carl Philipp Gottfried von Clausewitz).

“To shock people and have them in awe of you is a dominating thing,” he said. “It’s where you destroy and paralyze the enemy and they’re so stunned by the sheer force of your bombardment that they’re just incapable.”

“They’re two words that capture a chunk of what glam is about.”

The Department of History collaborated with the English, art history, music, and communication and media studies departments in sponsoring the talk.