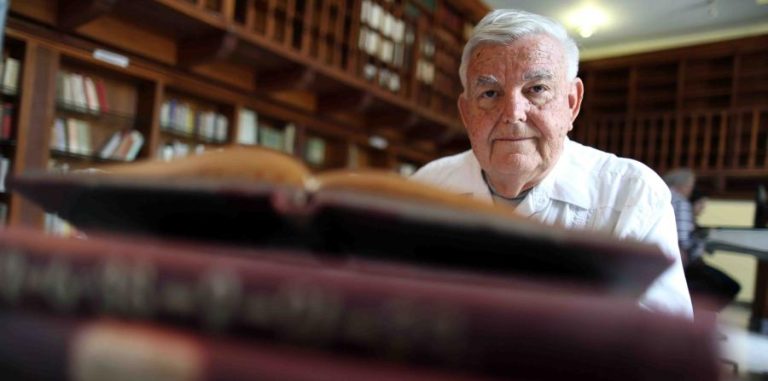

Fernando Picó, S.J., GSAS ’66, a leading Puerto Rican social historian of his time and a pioneer of Latino studies at Fordham, passed away on June 27 at the age of 76.

“He revolutionized Puerto Rican historiography by taking into account the perspectives of those who lived and experienced the world, as he was wont to say, ‘from the bottom up,’” said Arnaldo Cruz-Malavé, Ph.D., professor of Spanish and comparative literature and director of the Latin American and Latino Studies Institute (LALSI).Shortly after earning his doctorate in European medieval studies from Johns Hopkins University, Father Picó came back to a tumultuous campus at Fordham, where students had successfully agitated for changes in the curriculum to reflect the growing diversity of the student body. The Department of African and African American Studies had been established in 1969 and, through the efforts of the student group, El Grito de Lares, a Puerto Rican Studies program followed in the fall of 1970.

Two days before the first course was set to begin, however, the professor hired to teach the class bailed out. Joseph P. Fitzpatrick, S.J., GSAS ’41, a Fordham sociology professor who had researched the Puerto Rican migration to New York City, invited Father Picó to teach the class. At the time Father Pico had, in his words, only a “sketchy” knowledge of Puerto Rican history, but he accepted the position and began cramming.

“I was coming to Puerto Rican history with many questions; those of my prospective students were my own,” he wrote in the preface to his book Historia General de Puerto Rico (Marcus Weiner Publishers, 2005). The book is considered by many to be the definitive history of the island, said Cruz-Malavé.

The course became the cornerstone of what would eventually become the Latin American and Latino Studies Institute (LALSI). It was one of the first such programs in the country, Cruz-Malavé said.

El Grito de Lares, the student group that started it all, is still active on campus.

In his book, Father Picó acknowledged his experience at Fordham as the moment he pivoted from medieval history to the social history of Puerto Rico. He specifically credited Fordham Puerto Rican and Latino undergraduates for showing him the importance of viewing history from the “bottom up.”

“I have learned from all my students, but I learned more from these than from any others,” he wrote. “For them, the course was not a three-credit class to fill an academic record; it represented the fundamental university experience […] in Puerto Rican history. They came in order to find out who they were.”

“He remembered his students’ examples of seeing themselves as part of history, as protagonists in it rather than as its victims,” said Cruz-Malavé. “He saw their actions as an encouragement to research Puerto Rican history and to write a new kind of historiography, one based on the perspectives of those on the ‘bottom’ of historical processes.”

Cruz-Malavé said that Father Picó’s and Father Fitzpatrick’s pedagogy aimed to link critical thinking to engagement with social issues and service to communities they were studying. For Father Picó, that meant returning to Puerto Rico, where he eventually rose to become a distinguished professor at the University of Puerto Rico. Cruz-Malavé said he was admired for his many community-based projects, including his research and education of convicts, many of whom went on to receive a university degree.

“He was a scholar who was interested in working with ordinary people, and in the way they were not only acted upon by social phenomena, such as migration, but the way they could also be agents of change,” said Cruz-Malavé.