With 2.2 million incarcerated, the United States has the largest prison population in the world, bar none. Stricter laws, like the infamous three strikes laws, have increased the likelihood that the number of senior citizens behind bars will continue to grow.

On May 9, Tina Maschi, PhD, associate professor at the Graduate School of Social Service, released a comprehensive report that explores ethical, financial, and legal arguments for the compassionate release of incarcerated elders. Published by Be The Evidence, a non-profit social justice collective, the report titled “Analysis of United States Compassionate and Geriatric Release Laws” takes a close look at how various systems across the nation treat incarcerated elders or those with serious terminal illnesses.

Maschi said there has never been a comparison that analyzed state-by-state laws and regulations for compassionate release.

“We’re making a lot of decisions on policy that all to often are not based on evidence,” she said.

In the report, which looks at all 50 states, only Oregon emerges as one that considers the incarceration of sick older prisoners as cruel and inhumane. Some 47 out of 52 federal or state systems allow for the petition of compassionate release, but only 36 percent offer a clearly defined process.

Maschi said while many incarceration experts support early release from a humanitarian perspective, efforts to change laws are often stymied by fear- mongering.

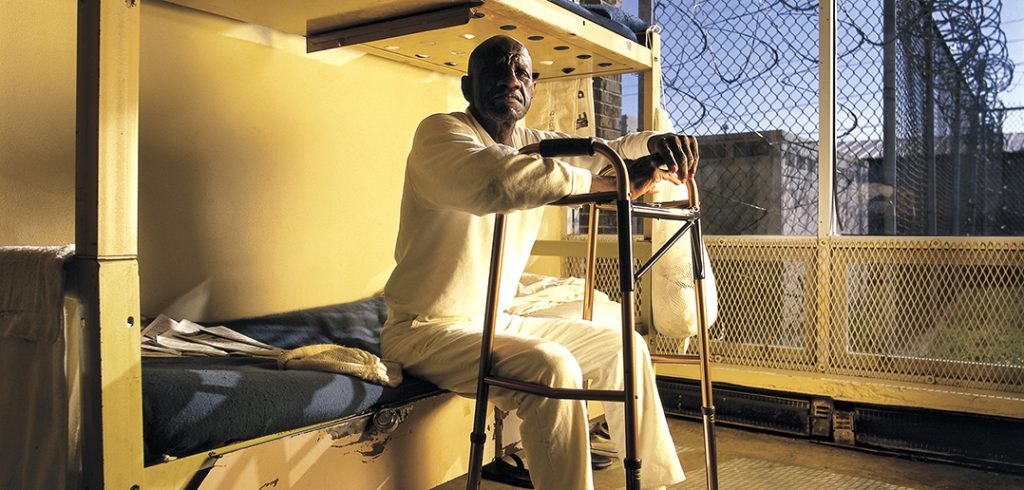

“We fear crime, we fear violence, getting old and dying” she said. “But fear should not blind us to the realities of too many people are old, sick, and dying in prison.”

In general, released seniors have a zero to 1 percent recidivism rate, said Maschi. And most laws dealing with compassionate release don’t allow people with violent and sex offenses to receive a compassionate furlough from prison.

She said that while there is some risk that someone with dementia may show aggression whether or not they have an incarceration history, the research shows that the dangers of violence by older people decreases with age. If anything, she said, the concern has more to do with caretakers mistreating the incarcerated elders, not the other way around.

Then there is the cost to consider.

“Older people in prison are accountable to pay with time for their crimes, but taxpayers are paying the bill,” she said. “We have to ask ourselves, do we want to continue to pay for the excessive staff of correctional officers, in addition the medical staff, for someone who can’t even get up to walk?”

Maschi warned that merely releasing incarcerated elders isn’t going to solve the overpopulation problem or associated costs to the public. She said that more social workers would be needed to find housing and other supports for the infirm and their families. While going home to family might be the best route for the older prisoners, more often than not it’s not an option.

Regardless whether a family or an institution provides care after the release, the security costs would be eliminated—and that’s a big savings, she said.

“It costs three to five times more to keep an elderly person in prison than a younger person. In numbers, that’s $68,000 compared to $22,000 annually,” she said.

Maschi cited a report released earlier this month by the Office of the Inspector General at the U.S. Department of Justice that analyzed the impact of the aging prison population within the federal system alone. The report stated that in 2013 the federal government spent approximately $881 million, or 19 percent of its total budget, to incarcerate aging inmates.

“With the release of these reports, people are beginning to ‘pay’ attention to the costly problem,” said Maschi.