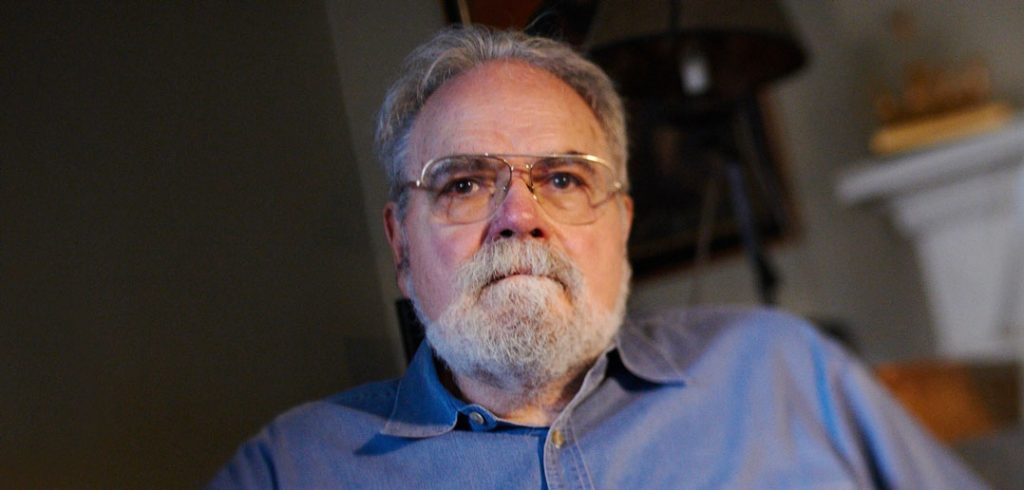

“Orlando was a quiet, thoughtful leader who was committed to the idea that we can keep each other safe and hold one another accountable without resorting to punishment,” said Professor of Sociology Jeanne Flavin, Ph.D. “He was someone who supported all students and his junior colleagues.”

A Symbolic Cup of Coffee

In 1987, Rodriguez joined Fordham as senior research associate at the University’s former Hispanic Research Center, where he studied mental health in Latinx communities. From 1990 to 1997, he served as the center’s director. Rodriguez also taught in the Sociology and Anthropology Department at Rose Hill, serving in several positions, including department chair, until his retirement in 2020.

He and his wife experienced a devastating loss during the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York City: the death of their son, Gregory, who worked on the 103rd floor of the World Trade Center. Four days later, they penned an open letter, “Not In Our Son’s Name,” asking the U.S. government to resist calls for military retaliation. Their letter was included in the book Voices of a People’s History of the United States (Seven Stories Press, 2004), inspiring a series of public readings on stages nationwide, as well as the 2009 film “The People Speak.” The story of their response to their son’s death was also spotlighted in the 2015 documentary “In Our Son’s Name,” aired on PBS.

Despite his pain, Rodriguez was resilient. “He would bring me a little cup of espresso in bed every morning before I got up,” said his wife, Phyllis Schafer Rodriguez, his partner of nearly six decades. “We both felt hopeless and devastated after Greg was killed. The next morning, after hardly sleeping … he walked in with two cups of espresso [for us]. That’s emblematic, in a quiet way, of who he was.”

At Fordham, Rodriguez turned his grief into action. With adjunct professor Kerry Sweet, he created and co-taught the course Terrorism and Society, profiled by The New York Times, which aimed to help students better understand terrorism. He was also instrumental in creating the Peace and Justice Studies minor program and the criminology course Harm and Justice, Crime and Punishment.

‘I Credit Him with the Person I Am Today’

Among his mentees was Tia Noelle Pratt, GSAS ’01, ’10, who said Rodriguez saved her career. He helped her to navigate a complex administrative issue, allowing her to finish her dissertation. And when she became temporarily homeless due to a fire, Rodriguez and his wife gave her a place to stay—their home.

“He taught me to keep going, even when it looks like you won’t get there,” said Pratt, who earned her master’s and doctorate degrees in sociology.

He championed scores of other students, including Stacy Torres, Ph.D., FCLC ’02, connecting her with life-changing opportunities, counseling her through personal issues, and helping her family deal with their post-9/11 grief, all while tending to his own.

“I credit him with the person I am today, and for helping me to reach my current position as a sociology professor myself,” said Torres, who now teaches at University of California, San Francisco.

Rodriguez was born in Havana, Cuba, on Feb. 22, 1942, to Marta Iglesias, a seamstress, and Jesus Rodriguez, a cracker salesman. When he was 13 years old, the family of three moved to New York City. Rodriguez graduated from Samuel J. Tilden High School in Brooklyn. He went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in sociology from City College of New York and a Ph.D. in sociology from Columbia University. Besides working at Fordham, where he spent most of his academic career, he taught at Brooklyn College and conducted research at the Vera Institute of Justice. He also taught sociology of religion at the Green Haven and Sing Sing correctional facilities in New York state as a volunteer at Rising Hope, a college-level certificate program.

In his day-to-day life, Rodriguez was a quiet man who spoke judiciously, while entertaining people with his dry sense of humor and witty one-liners, said those who knew him. He was also an avid reader of fiction, nonfiction, science fiction, and detective novels. He attended the Memorial United Methodist Church in White Plains, New York, and participated in Braver Angels, an organization that promotes civil conversations across political differences.

Rodriguez is survived by his wife; daughter, Julia E. Rodriguez and her husband, Charles B. Forcey; daughter-in-law, Elizabeth Soudant; and three grandchildren. He is predeceased by his son.

A private burial was held on Jan. 13 at White Plains Rural Cemetery. A public memorial service will be held this spring. Donations in his memory may be made to Rising Hope or Peaceful Tomorrows.

Watch the documentary trailer for “In Our Son’s Name” below.