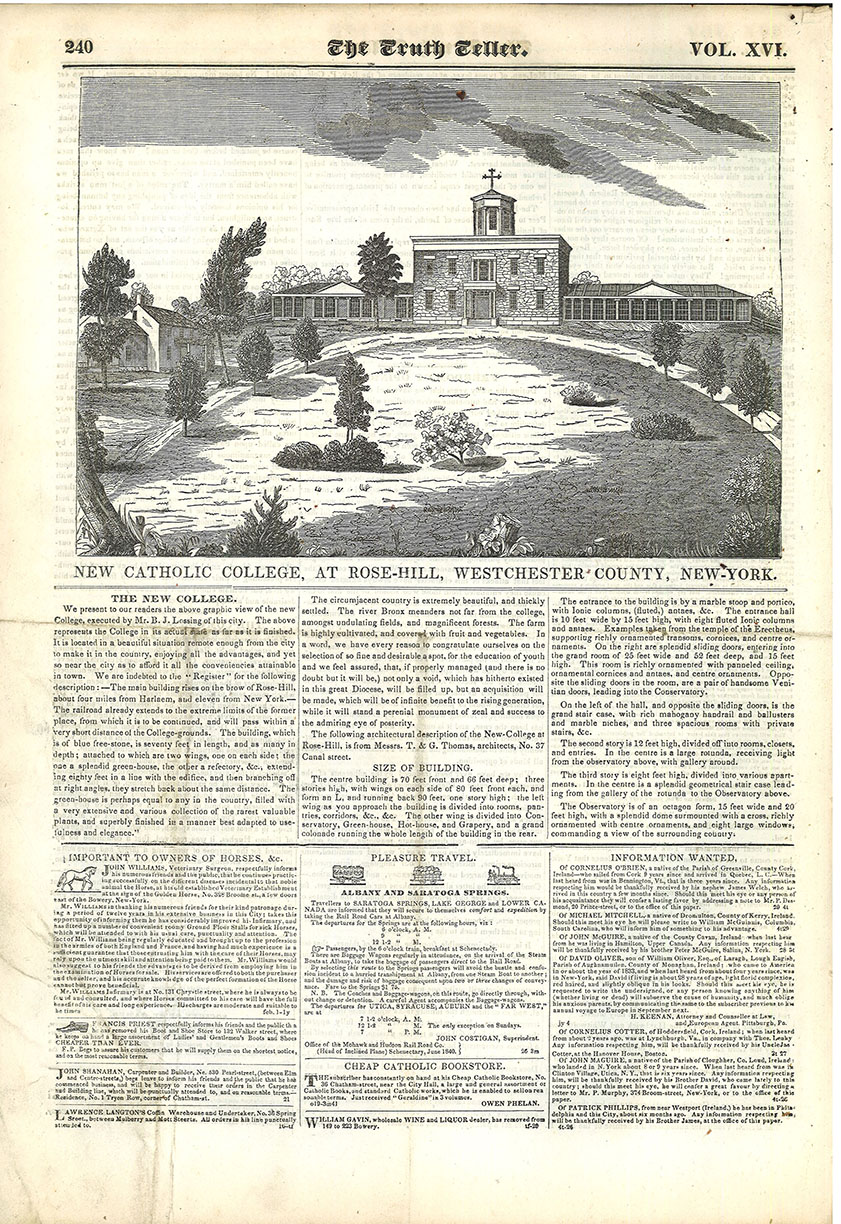

Last November, Wines found the image in an 1840 article about the then-new college while he was “systematically” sifting through periodicals at the Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. He came across an issue of the Catholic newspaper the Truth Teller with a headline “New Catholic College, at Rose Hill, Westchester County, New-York.” The article appeared a year before the institution, which would become Fordham, was founded as St. John’s College. It was also a time when Westchester still held jurisdiction over the area, and when New-York was still hyphenated.

“I think it’s probably the only copy in the world and this was probably included as part of the original fundraising campaign to get the college started,” Wines said. “These are newspapers that are not indexed on Google. You have to actually just go page by page.”

Wines said that historians like himself have to go where the material is. In many cases, Fordham’s history is spread out among several libraries, from O’Hare Special Collections at Fordham’s Walsh Family Library to Columbia University’s Avery Library to the Hesburgh Libraries at the University of Notre Dame.

“The fact is we can’t bring everything to Fordham, so we bring the information and then we tell people where we found the information,” said Wines.

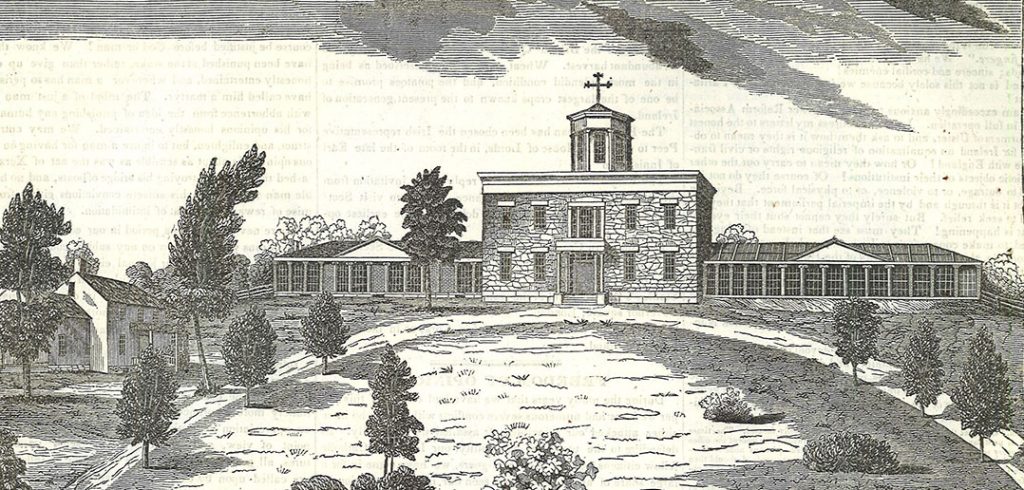

The woodcut print reveals many lost details of the original building, and the accompanying article brings to light information about the building’s interiors as well as the heretofore unknown, if somewhat repetitive, name of the architect: Thomas Thomas (1781-1871), a well-established architect who was also working on St. Peter’s Church on Barclay Street in Manhattan.

The new building’s entrance opened onto a central hall with a spiral staircase that swept up to the second floor and a rooftop lantern, providing light and ventilation. A southern room of the house—now the president’s office—was, fittingly, a chapel. Just off the chapel was a working greenhouse. The northern wing served as a refectory. A back porch overlooked a pasture that is now Edwards Parade, and the marble Greek Revival front steps, still in use today, looked out on Martyrs’ Lawn.

From Teacups to a Manor House, Excavating Rose Hill

Gilbert and Wines have spent a good portion of their careers researching Fordham’s history. Gilbert is the editor of Digging the Bronx: Recent Archeology in the Borough (The Bronx County Historical Society, 2018), which includes a chapter written with Wines titled “Seventeen Years Excavating at Rose Hill Manor.” The book takes a practical look at archeology in the Bronx, including a chapter on the business of archeology to specific cases, as well as case examples of excavations in Van Cortland Park, Riverdale, as well as Rose Hill.

Gilbert said the 70-page chapter on Rose Hill is just an overview of the 17-year excavation. The excavations, which began in 1985, allowed scores of students from history and archeology classes to uncover everything from teacups to religious medals to the foundations of the original buildings, including Rose Hill Manor, which was razed in 1896 to make way for Collins Hall. Much of the material that was excavated fills rooms in Dealy Hall and in the basement of Cunniffe.

“If you look at the college’s history from 1890, the original Manor House was said to have been [George] Washington’s headquarters. That is romantic, but he probably just rode by on a horse,” said Wines, before adding, “We discovered in Washington’s papers that during 1776, a detachment of colonial troops was on campus. They were camped in the orchard. We found him coming back again in 1781.”

Dispelling campus lore is a necessary part of the job, said Gilbert.

“In our business, we’re trying to uncover as much new information as possible about what this place was like. Decades, centuries ago, before the college came here,” Gilbert said. “Ultimately, what we discovered, and what we probably knew subconsciously anyway, is that when local histories are put together, they’re frequently put together very quickly with very little information and that once those narratives form, they become fossilized.”

Staying Power

The drawing of Cunniffe House depicts the early days of an institution whose students would go on to bear witness to a civil war, two world wars, Vietnam, 9/11, as well as the current coronavirus crisis, which, with the recent wholesale shift from face-to-face interaction to online interaction, is unique in Fordham’s history.

The college held classes throughout the Civil War, World War I, and World War II. The 9/11 tragedy caused disruptions, but there was not any notice to vacate campus, said Gilbert. Wines said that campus protests during the Vietnam War are the closest parallel. The upheaval forced the administration to send students home and faculty were instructed to grade them on the basis of work completed for the semester—but this was well before laptops and Zoom allowed for instruction to continue, he said.

While Gilbert and Wines agreed that many romanticize the past, sometimes Fordham’s history can be quite, well, romantic. On reading the 1840 description of today’s Cunniffe House in the Truth Teller article, it’s hard not to be taken in by purple prose, some of which holds to this day.

“It is located in a beautiful situation remote enough from the city to make it in the country, enjoying all the advantages, and yet so near the city as to afford it all the conveniences attainable in town,” reads the text accompanying the image.

The article continues on to delve into the architectural details of the “blue free-stone building,” mentions the new railroad that was being built a short distance from the college, and waxes poetically about how the “river Bronx meanders not far from the college, amongst undulating fields, and magnificent forests.”

When the image of Fordham appeared in the Truth Teller, University founder Archbishop John Hughes was still 13 years away from announcing the construction of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. For the newspaper’s Catholic readership, the new college represented hope and staying power for the future. One particular phrase in the text accompanying the image, still resonates, particularly now:

“…[I]t will stand a perineal monument of zeal and success to the admiring eye of posterity.”