The exhibition, which was unveiled at an open house on April 16 in the O’Hare Special Collections Library, will run through the end of May. A second open house will be held on May 7 at 6 p.m.

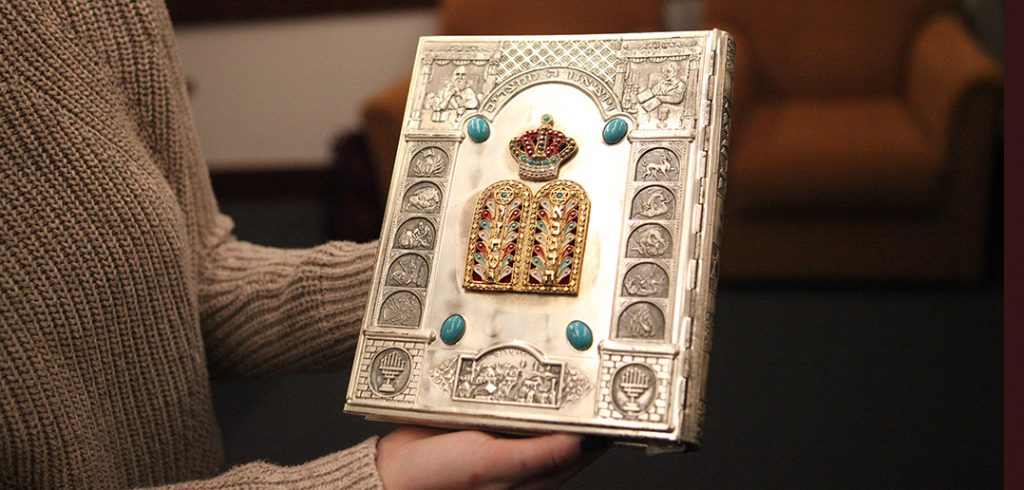

Teter has been growing Fordham’s collection of Hebrew texts for some time now, and the Haggadot (plural of Haggadah) reflect an overall curatorial vision of mixing the common household texts with high-quality facsimiles of The Barcelona Haggadah and from the Rothschild Miscellany, donated by longtime library patron James Leach, M.D. As in years past, the Maxwell House Coffee Haggadah, a common sight in many a middle-class Jewish home, sits near rare 18th-century versions.

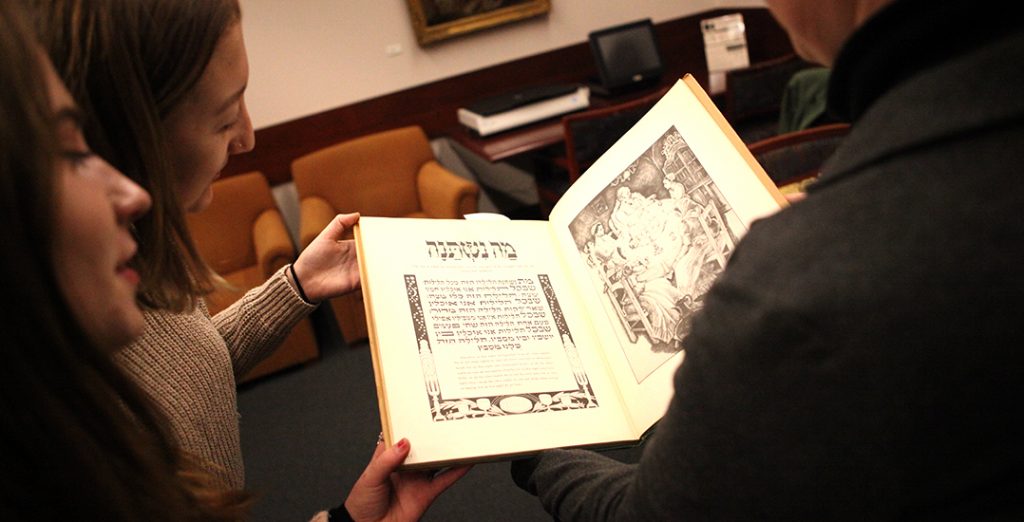

The exhibit was co-curated with Rose Hill seniors Emma Fingleton and Zowie Kemery, both Jewish studies minors, and sophomore Margaret Keiley. The project began at the start of the semester in early February. The students met with Teter to see and, more importantly, handle the texts.

“It’s not behind a glass plane; it’s right in front of you and you can touch it,” Fingleton said of one of the texts at the time.

Indeed, as Fingleton and Keiley grazed their hands across the paper, they remarked on the impressions left behind by an 18th-century letterpress.

“People actually use these objects, it’s very different from reading it online on a PDF,” said Keiley.

This year’s exhibition differs from the 2016 show, which expanded on Jewish-Christian relations. Instead, this show takes visitors on a world tour through nations and time. There were plenty of texts to choose from. The collection includes Haggadot from Egypt, Ethiopia, Sweden, Germany, and Holland. There is a vegetarian-focused Haggadah called The Liberated Lamb. There are Haggadot that were distributed at displacement camps just after World War II. And there are two from the same publisher that seem exactly the same except for one detail on the title page: One was printed in Palestine in 1948, just before the State of Israel was created; the other was printed in the exact same geographical place in 1953, when it was Israel.

“It’s a global story told in different languages, but the same culture,” said Teter.

Some of the pages come alive with past use. In particular, there are the pages with wine stains, which represent a moment during the Seder when the plagues are mentioned and “you put a finger in the glass of wine and sprinkle it on the text,” said Teter. It was a particularly moving gesture to the students.

“It all resonates in ways that remind me of archeology. It brings you to their perspective, even if it’s something as simple as a wine stain,” said Fingleton. “I feel more open towards the value these things have. It really impacts your view.”