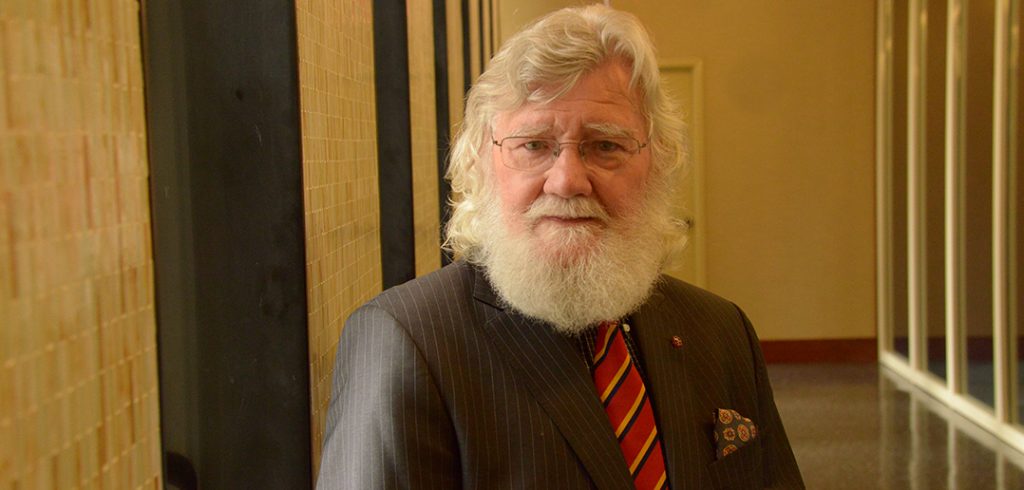

Larry Hollingworth, CBE, visiting professor at the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs (IIHA), has worked in humanitarian aid agencies since the 1980s. Prior to that, he served in 19 countries as a member of the British Army. He creates curriculum and teaches in Fordham’s International Diploma in Humanitarian Assistance (IDHA) program, and has taught the program’s courses in more than 20 countries.

- What is the single biggest obstacle facing humanitarian aid workers today?

Without a doubt, the single biggest obstacle is access. We are able to produce a lot of the resources that are needed by the beneficiaries—those refugees or displaced persons. Our problem is that we can’t get to them.

In many of the countries where we operate, we can’t deliver food and other things because of political obstacles. For example, to deliver aid in Syria today, agencies have to cooperate with whatever limits [President] Assad wants to impose—that includes which agency we can deliver aid through, and where the aid can go. Obviously he is not going send aid into the areas that are opposing him. Therefore it makes it very difficult to deliver aid neutrally, impartially, and independently. There are enclaves where no medicine has gone in for years, no anesthetics. You are putting people in medieval conditions. And it’s not just Syria. Almost everywhere we go, oppositions want to stop humanitarian agencies from delivering aid.

- Is there another significant obstacle?

The other point is that money is tight. We are probably about a billion dollars short for the crises we have today in the world. In the 1990s most of the large agencies were a third of the size they are today and there were not many small independent NGOS. If a crisis got 20 or 30 agencies, that was a good turnout.

There were more than a 1,000 agencies that responded to the 2010 Haiti earthquake crisis. Where did they all come from and the question we could ask—which is suitable to this ground—is how qualified are they to be there? No one wants to deny the good heart, but there are too many agencies vying for the same monies.

- Is forced migration overloading global humanitarian efforts?

The migration problem is massive. In the humanitarian aid world, we work with internally displaced people and refugees forced from their countries [as opposed to economic migrants]. People are fleeing from violence. They are saying there are 65 million people displaced in the world, a huge number. And it doesn’t seem to be getting any lower.

The economic migrant is the larger portion of migrants–coming from countries in desperate straights because of climate disasters or violence. It is very difficult to measure their numbers, very difficult to control them, very difficult to send them back, and very difficult to house them in your country.

Sadly, the animosity and aggravation that people have toward migrants is going to grow. To be honest, migrant populations are one lever for Britain to have made the choice that it did last week [on Brexit].

If there was peace and there were jobs in their own countries, most migrants would stay. Some people say wouldn’t it be better spending our money on creating peace, rather than providing aid for the people who are displaced. Now, we are back into money and political will.

But we are not doing enough about prevention.

- How does the IDHA program address these problems?

One of the strengths of the program is that we are up to date. We look at every crisis as it is today, not from 5 years ago. Every student that we have is going out to today’s crises, and what we did a decade ago no longer applies.The moment you get on the ground in any crisis, in the first few hours everything changes. The police should be there; they’re not. The government should be there; it’s not. Everything is changing constantly.

In order to make sure we are up to date, we change our lecturers each and every term. We bring them in strait out of the field. This session we had a young Kenyan woman who has been in the field for 5 or 6 years. We have two people who were just in Gaza. These lecturers can talk about the ethical or political questions, or even about communications problems, because they were literally just there.

Whether they can tell us that ‘it worked,’ or ‘it would work better with something else,’ they remind us that humanitarian aid is a moving philosophy—and you have to go with it.