But Kattan Gribetz had come across a curious fact: Many Koreans read the Talmud.

Kattan Gribetz had seen a news article and one television clip on the Talmud’s immense popularity in Korea. On a whim, she ordered copies of the Korean translation, even though she didn’t speak or read the language.

As chance would have it, Kim went to Kattan Gribetz’s office to pick up a paper from class, and Kattan Gribetz asked her if she had ever heard of the Korea-Talmud connection. Kim, who grew up in Southern California and went to a Korean school on the weekends, said she told her professor that the perception of popularity must be overblown.

Later that day, however, she called her mother and asked if she had heard of the Talmud.

“She told me that everyone in Korea has a copy of the Talmud, though she didn’t realize it was a religious text,” said Kim.

Thus began a two-year research project of translating and comparing the Korean versions to the Babylonian Talmud and other ancient rabbinic texts.

The project was fostered through the University’s Undergraduate Research Program (LINK). Together, Kim and Kattan Gribetz attended two conferences in two countries and produced a paper, “The Talmud in Korea: A Study in the Reception of Rabbinic Literature,” that will soon be published by the Association for Jewish Studies Review.

Along the way, Kim said the project also brought her closer to her parents and her culture.

“I called them a lot more because I had so many questions about certain words or nuances I couldn’t pick up on, because I wasn’t born and raised in Korea,” said Kim. “I pride myself on being a part of two different cultures, but this was definitely a wakeup call; there are a lot of things I don’t know about Korea.”

Kattan Gribetz said their research explored the roundabout journey of the Korean Talmud. In the late 1960s, Rabbi Marvin Tokayer, who had been stationed in Tokyo and Seoul as a chaplain with U.S. Air Force earlier in his career, returned to Japan as a rabbi. There, a Japanese historian convinced him that a translation of the Talmud could be popular in Japan because people were curious about Judaism and Jewish history. In his book, Tokayer dispensed with the Talmud’s specifically Jewish laws and rules, and focused on themes that would resonate with a Japanese audience, such as hospitality, education, and kindness.

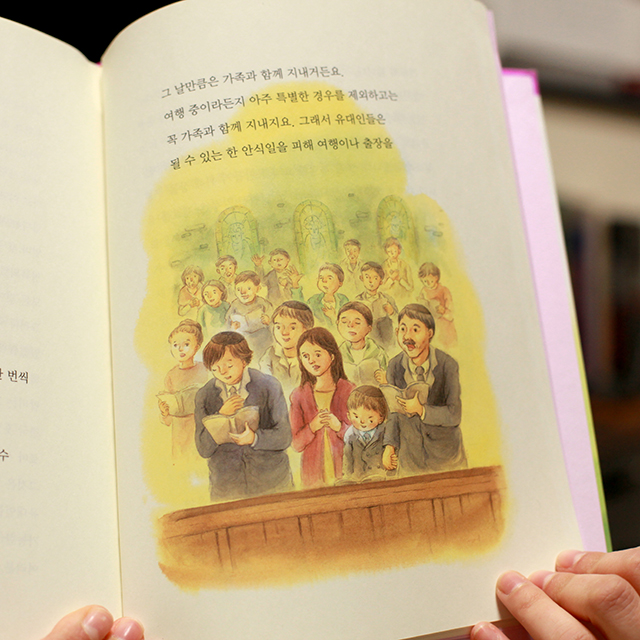

At some point, said Kattan Gribetz, Tokayer’s highly edited anthology of Talmudic stories found its way into a Korean translation. Illustrations and aphorisms were added, making the Korean version closer to Aesop’s Fables than to the rabbinic texts with which most Jews would be familiar.

“It’s strange that there’s such a small connection between the Babylonian Talmud and these books, and we were curious to see who was writing them and where they came from,” said Kim.

The two read through dozens of Korean versions and presented their findings at the 2016 international conference of the Society of Biblical Literature—which happened to be taking place in Seoul, South Korea. This past December they presented the research again in Kim’s hometown of San Diego at the Association for Jewish Studies conference.

“I couldn’t read the text without Claire, and she didn’t know enough about rabbinic sources to connect the two,” said Kattan Gribetz. “Ours was the perfect collaboration.”

Kim, who double majored in English and art history, graduated on Feb. 1. She is now interning in the education department at the Guggenheim Museum and at the Asian American Arts Alliance. She said the project was a highlight of her time at Fordham.

“I know that it is rare for a university professor to be working with an undergraduate student on a research project like this, as well as to continue fostering me through submitting the article after graduation,” she said. “Being able to experience all of it with Dr. Kattan Gribetz and my parents was just lovely.”