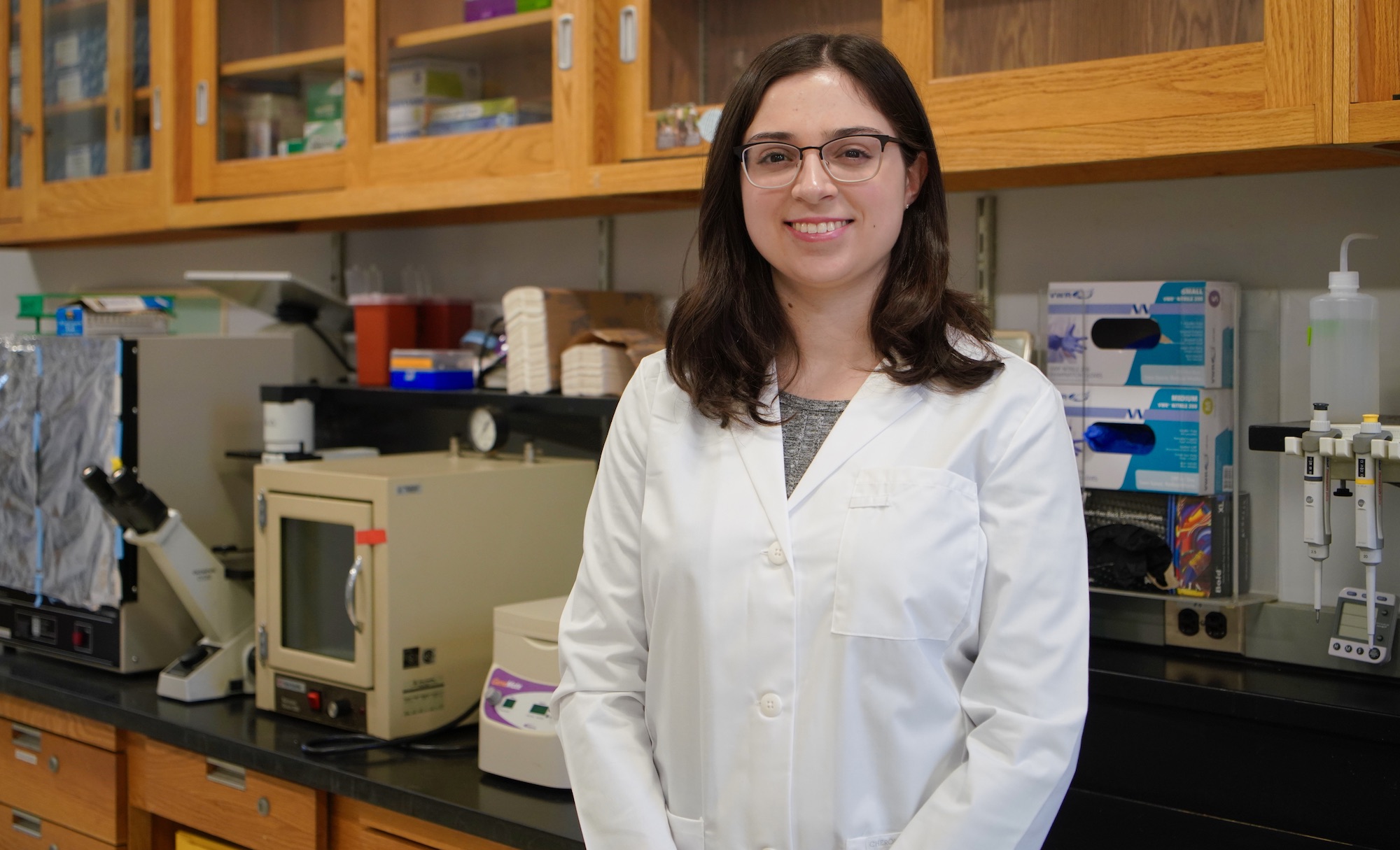

“I haven’t pinpointed what I specifically want to work on, but I’m eager to do research that has some kind of positive impact on the world, whether that’s helping people or the environment,” Bonanni said. “I want my research to have a bigger purpose.”

Some student researchers focus on a single topic, but Bonanni has dabbled in several—and because of this, she sees the world differently, said a Fordham professor.

“Her experience has given her a good view of different topics. She can ask questions that other people might not be thinking about,” said her academic advisor Patricio Meneses, Ph.D., associate professor of biological sciences. “This will benefit her when it comes to asking the next interesting or necessary question in science.”

‘A Whole New World Opened Up’

Bonanni was born to a family of scientists in Niskayuna, New York. Her father is an electrical engineer at General Electric. Her mother, a longtime optometrist, pursued her career when there were few women in her field. Both inspired their daughter to become a researcher.

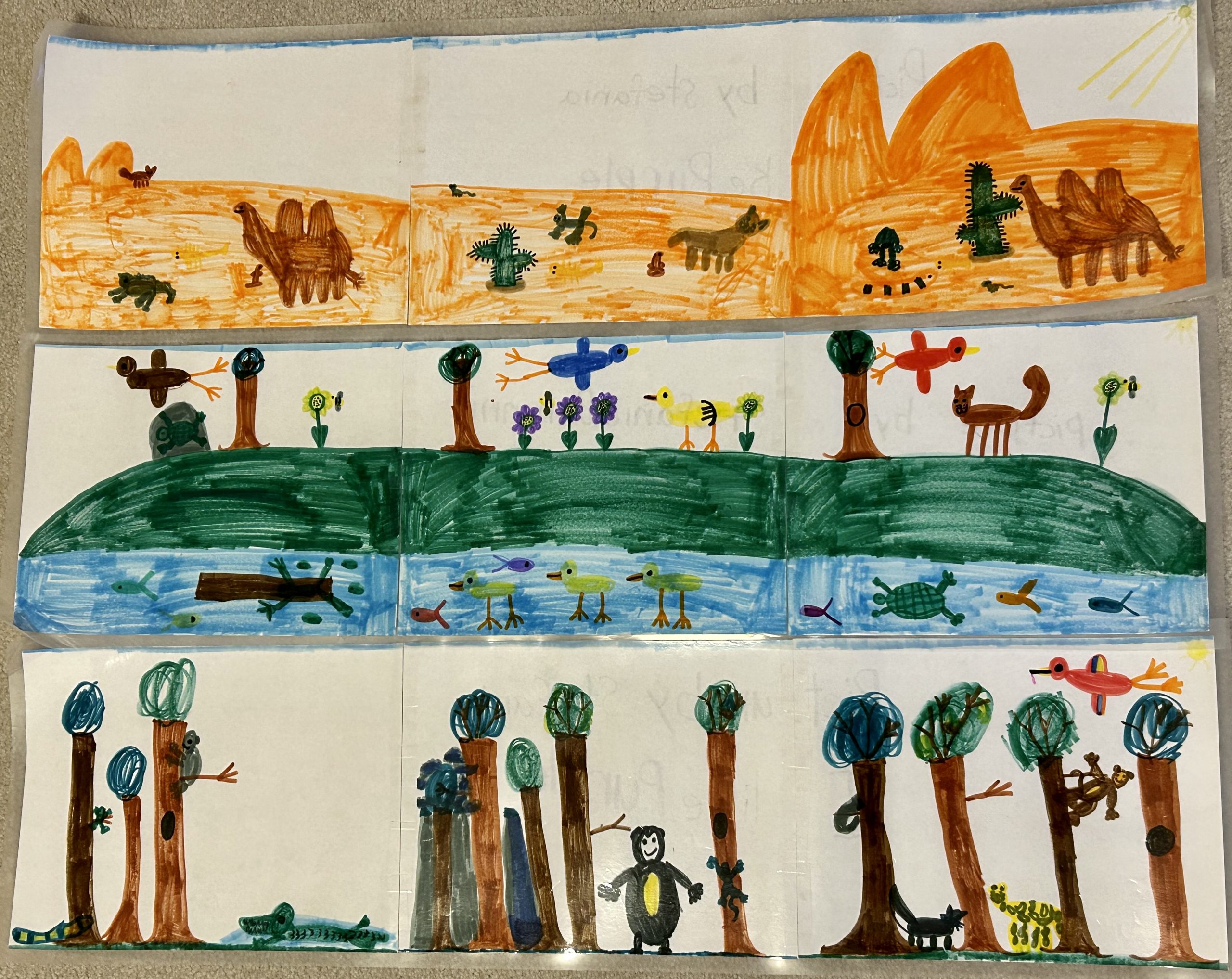

Bonanni had always been fascinated by the natural world. In elementary school, she drew three-page pictures of different landscapes and the flora and fauna that lived within them. But in high school, Bonanni realized that science was more than a childhood interest.

“When I took a biology course, it was like a whole new world opened up. I learned how the natural world works, how everything fits together in ecosystems, and how life functions. Once I knew that was a field, I was like, ‘Wow—that’s the one for me,’” she said.

Growing as a Biologist at Fordham

In 2020, she enrolled at Fordham. She wanted to attend school in New York City, and she was drawn to Fordham’s Jesuit ideals.

“I knew that I could find a Catholic community at other colleges, but I liked how Fordham implements the Jesuit values in their course philosophy,” she said.

Bonanni spent her first year on Zoom due to the pandemic. The following summer, she took two tuition-free classes. Among them was a genetics course with biology professor Edward Dubrovsky, Ph.D., whose work she loved so much that she asked if she could work in his lab.

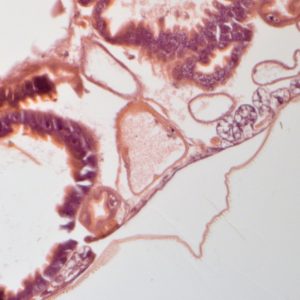

Throughout her sophomore year, they examined the genetic mutations responsible for cardiomyopathy, a disease that thickens heart tissue and can lead to death. Using fruit flies as a model for the human body, they explored a question: Where do the mutated genes that cause cardiomyopathy need to be located in order for symptoms to develop? Any cell in the body or specifically in the heart? (They later learned that the latter was correct.)

Under Dubrovsky, Bonanni learned what it’s like to work in a real lab, versus a classroom.

“When you’re in a research lab, you don’t know what the answer is. Sometimes things don’t go right the first time, but that’s just part of the research process,” Bonanni said. “That uncertainty is where discoveries are made.”

The following summer, she studied in Australia through Fordham’s partnership with the School for Field Studies. For one month, she lived in the rainforest and conducted fieldwork on marsupials.

“It was really cool to learn about how they came to be in Australia and set up field cameras to take pictures of marsupials passing by, like pademelons,” Bonanni said.

Exploring Bronx Plant Life

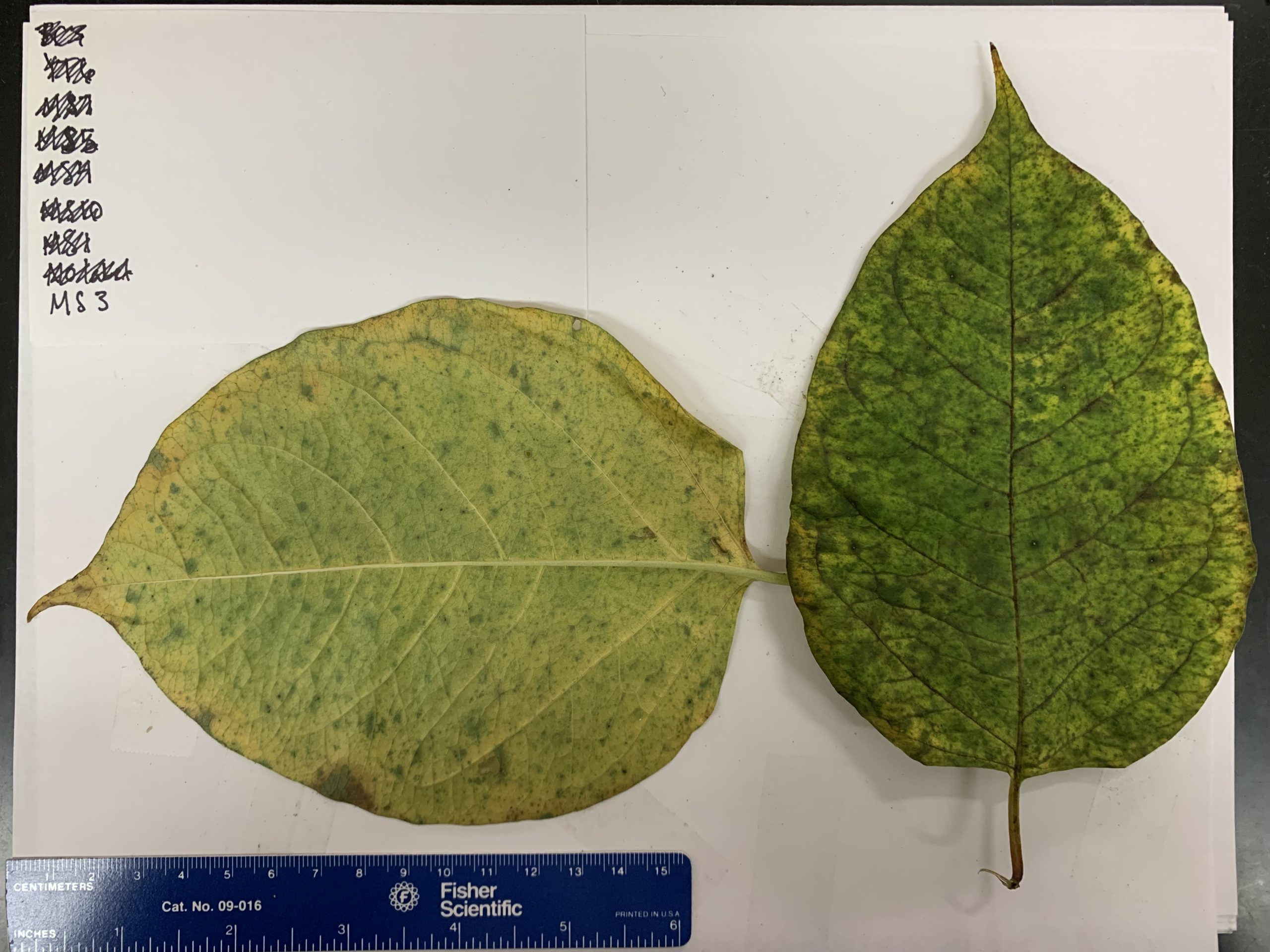

She loved working with animals, but she also wanted to try working with plants. She had always enjoyed tending to her family’s vegetable garden, where they raised tomatoes, lettuce, squash, and beans.

Last fall, she studied the spread of Japanese knotweed, an invasive species that has spread to the Bronx, in the lab of biology professor Steven J. Franks, Ph.D. She enjoyed the experience, but realized she preferred working with animal cells.

Keeping the Earth Safe for Turtles

This semester, Bonanni started working on a project that combines her interests in cell and molecular biology and ecology.

In the lab of Evon Hekkala, Ph.D., associate professor of biological sciences, Bonanni is studying green sea turtles, the largest hard-shelled sea turtle on Earth. Every year, these turtles return to the same beach to lay their eggs. The problem is only some areas are protected from poaching and other activities that prevent babies from hatching and safely making their way to the ocean.

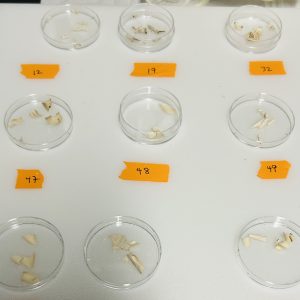

“If only specific areas are protected, then only specific turtle genes might be protected. That means you’re limiting the genetic diversity of the population,” Bonanni said. “A less genetically diverse population is less likely to survive diseases,” said Bonanni, who is now analyzing DNA from hatched turtle shells to assess their genetic diversity.

The Wonder of the Natural World

Bonanni wants to become a biologist. No matter what she focuses on, she says she wants to hold onto something that we often forget as adults—the wonder of the natural world.

“Growing plants is so exciting when you really think about it,” said Bonanni, who once worked as a summer camp counselor who taught children how to water seeds into sunflowers. “The fact that a beautiful, green, lush thing can come out of a small seed is so cool. As adults, we sometimes lose the wonder associated with that. But when you look at a kid experiencing it for the first time, you remember how exciting it really is.”