Can we use the ocean to meet our basic needs without depleting it?

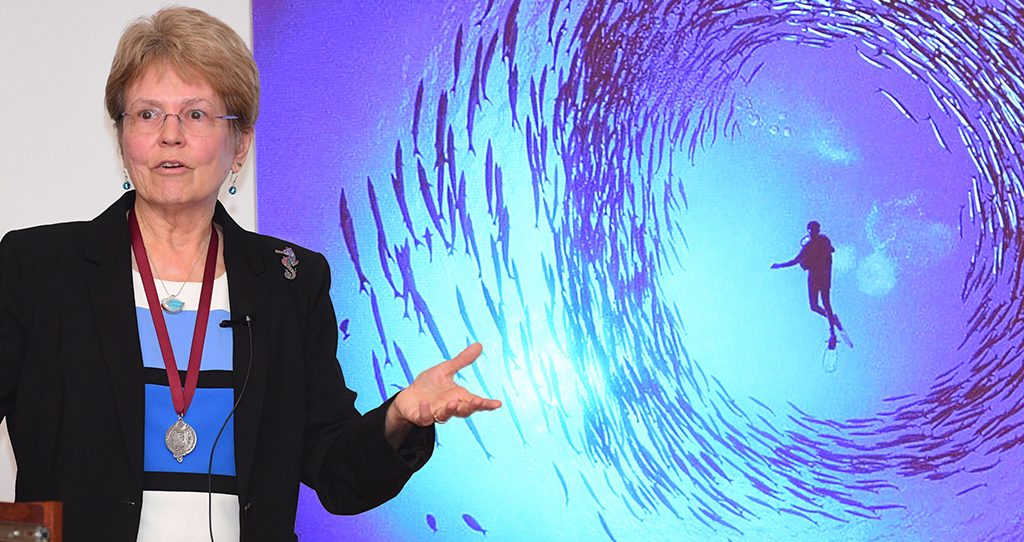

At the Sapientia et Doctrina lecture, “Making Waves and Bringing Hope: Our Role in Charting the Future of the Ocean,” world-renowned marine ecologist Jane Lubchenco said there are limits to what human impact the oceans can withstand. However, community-driven, holistic, ethical, and science-based approaches can lead to equitable and sustainable uses of ecosystems and marine resources.

Lubchenco’s lecture, held on March 22 in the Flom Auditorium of the Rose Hill campus, coincided with the United Nation’s World Water Day, which seeks to inspire action in the global water crisis. The lecture was sponsored by Fordham College at Rose Hill to commemorate Fordham’s Dodransbicentennial.

Before the lecture, Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, awarded Lubchenco, a former undersecretary of commerce for oceans and atmosphere and administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Sapientia et Doctrina medal in recognition of her commitment to issues related to the ocean and interactions between the environment and human well-being.

“You have now become a part of our family—175 years of women and men working together to seek wisdom [and]learning so that they might serve the world with a very firm sense of purpose,” said Fr. McShane. “And that purpose is transforming the world, one mark [and]one soul at a time.”

Challenges to sustainability

Lubchenco outlined the important functions of the ocean, the activities that have threatened its future, and those global innovative solutions that are promoting its sustainability.

From food and oxygen to climate and disease regulation, marine ecosystems provide multiple benefits to communities around the world. But a variety of activities on land and in the waters, such as habitat loss and overfishing, are threatening the provision of these services, Lubchenco said. These activities have contributed to plastic pollution, acidification, collapsing fisheries, coral bleaching, and low levels of oxygen in the ocean.

“We now have climate change as an overlay on top of all of those other things, plus ocean acidification. As the ocean is absorbing carbon dioxide, that in turn is making [it]more acidic,” she said.

“At the same time that all of that is happening, we want more and more from the ocean.”

The right incentives

Across the world, there has also been a surge in people’s dependence of seafood, she said.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ 2016 State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, the share of fish stocks within biologically sustainable levels decreased from 90 percent in 1974 to 68.6 percent in 2013. The report states that “31.4 percent of fish stocks were estimated as [having been]fished at a biologically unsustainable level and therefore overfished.” What’s more, illegal and unregulated fishing has left the ocean with few safe havens for fishes.

Lubchenco said economic and social incentives that focus on sustained benefits could help curb unsustainable practices, especially those incentives that involve science-based policies. She highlighted the mandates to end overfishing, enacted in developing countries like Belize and the Philippines, as successful sustainability-based programs.

“We’re learning through painful experiences how to fish smarter not harder,” said Lubchenco. “That means essentially [that we’re]. . . letting populations come back, and then fishing them in a higher level of abundance in a way that’s sustainable.”

Lubchenco argued in favor of evidence-supported, rights-based management, a system of allocating fishing licenses to fishermen, businesses, and other fishing communities. Such management ultimately provides short and long-term benefits to fishermen who are “good stewards” of the ocean.

“If you get incentives right for the fishermen, changes can happen really fast,” she said. “The question is how do you get there? What’s the incentive for them to make the effort?”

Hope for the future

While data and scientific evidence are important to move communities toward change, so is a moral and ethical commitment, Lubchenco said.

“That can’t happen in a vacuum,” she said. “That means engaging society, businesses, government, [and]communities and being more integrated into the world.”

Lubchenco encouraged Fordham students to do their part in creating a healthier ocean by staying informed, reducing their carbon and water footprints, eating lower on the food chain and communicating their environmental concerns to friends, family, and elected officials.

“Healthy oceans matter,” said Lubchenco. “They matter in part because they are an expression of our commitment to one another, and our commitment to life on the planet and our future.”