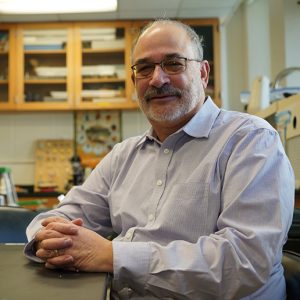

Jason Morris, Ph.D., professor and chair of Natural Sciences, said the honor is fitting, noting Botton “literally edited the book on horseshoe crabs.” Botton has been studying the crabs since the 1970s and is considered an expert internationally. Not only has he published extensively about the crabs in numerous scientific papers, his research has also been tailored to inform policymakers on how to proceed with beach replenishment projects in a manner that aims to balance the needs of the crabs with those of humans. He is a co-editor of Changing Global Perspectives on Horseshoe Crab Biology, Conservation and Management (Springer, 2015). He also co-chairs the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Horseshoe Crab Specialist Group.

The horseshoe crab fossil received its new name via a paper written by Russell D. C. Bicknell, Ph.D., a post-doctoral research fellow at the University of New England in Armidale, Australia, and Stephan Pates, Ph.D., of Harvard University’s Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, which appeared in the journal Scientific Reports. In an email from Australia, Bicknell called Botton “an exceptional colleague.”

Botton said the honor took him totally by surprise.

“The naming of the species for me was out of nowhere; I had no inkling that a new species had been found, much less that they decided to name it after me,” he said, adding that he was very flattered.

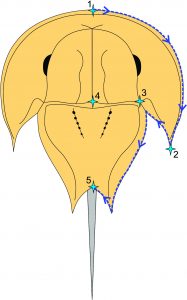

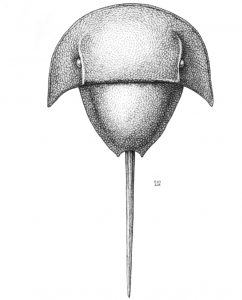

Horseshoe crabs alive today are very similar to their ancient cousins, leading many to call them “living fossils.”

While they may have changed little over hundreds of millions of years, that does not mean the staying power of horseshoe crabs is assured for millions of years to come. Botton noted that the American horseshoe crab is officially listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of endangered and threatened species.

“There are populations that are relatively healthy, but in New England and in the south of Florida, the populations are small and considered to be more at risk,” he said. “We also recently completed a revision of the status of the so-called tri-spine horseshoe crab,” he said.

The tri-spine is also known as the Chinese horseshoe crab in China and the Japanese horseshoe crab in Japan. He said scientists must be careful what they call that species, so as to not offend the Chinese by calling it the Japanese horseshoe crab, or vice versa.

“We (the international scientific community) decided to go with an older, more neutral name of tri-spine horseshoe crab; that way everybody’s happy,” he said, unwittingly noting the importance in a name. “That’s why I prefer to use the Latin names, but most people don’t.”

Regardless of the name one chooses, the tri-spine species is now listed as endangered, due to the crabs’ use for medical purposes and for food. The rise of sea level and the loss of spawning habitat pose another, broader threat.

“A lot of areas that used to be beaches where horseshoe crabs could lay eggs have now been developed either for industry, housing, or where they put up sea walls, all of which all take away the spawning habitat,” he said.

Here in the United States, the dangers to American horseshoe crabs come from fisheries that chop the crabs up and put them in traps that are used to catch eels and whelks, he said. Also in the U.S., the crabs’ blue blood is harvested for medicinal purposes, but that only accounts for a mere 10 to 15% mortality loss of the crabs caught for that purpose.

“They don’t bleed them bone dry. Just like when you go to give blood, they don’t take everything out of you. They want the animal to survive. So, there’s some stress due to handling and taking them out of water and so forth. But the estimates of the blood-related mortality are much less than the direct mortality from using them as bait,” he said.

Though he is personally concerned with the fate of the crabs, he said he doesn’t opine on conservation matters in his classes which are part of the Environmental Science Program he co-directs. Instead, he simply presents the science and lets students draw their own conclusions.

“When I’m in class I don’t try to steer a conversation in a particular direction. These can be viewed as political issues. I think some of the students almost want me to be more opinionated, but I don’t feel it’s my place. I feel it’s my place to give them the facts and let them judge.”

Nevertheless, he said his students talk to each other all the time about environmental issues and they tend to be “a pretty passionate group.”

“I mean, it’s hard to ignore what’s going on outside of the classroom right now,” he said.