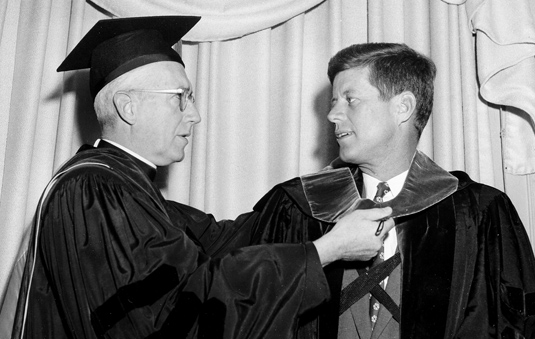

Photo by Ken Levinson

Q&A: Dean Michael Latham, Fordham College at Rose Hill

Michael Latham, Ph.D., dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill and professor of history, is the author ofThe Right Kind of Revolution: Modernization, Development, and U.S. Foreign Policy from the Cold War to the Present (Cornell University Press, 2011) and Modernization as Ideology: American Social Science and “Nation Building” in the Kennedy Era(University of North Carolina Press, 2000). Latham spoke with Inside Fordham about the John F. Kennedy presidency, reflecting on the upcoming 50th anniversary of the JFK assassination.

Q. What was the vision that enabled Kennedy to win the 1960 presidential election?

A. It’s important to remember that he came into office following a very narrow election; he barely squeaked by. As a Catholic, he was an outsider in some ways, but coming from Harvard certainly helped him. He was also a comparatively inexperienced politician, although he was well connected among American intellectuals and strategic thinkers.

Regarding foreign policy, he was very much a creature of the Cold War, and subscribed to its ideological constructs, including the imperative of global containment and the domino theory. If you read his inaugural address, what you see is not only a soaring idealism and inspiration but a determination to, as he put it, let every nation know “whether it wishes us well or ill, we will pay any price, we will bear any burden in the defense of freedom”—making it clear to any adversary that the United States would not fail in this obligation. If you look at the Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba, he didn’t ask the tough questions. He took the advice and guidance of the CIA and Defense Department officials who were convinced that they could remove Fidel Castro, and things went badly wrong.

But you also see a president who learns from these mistakes. You could argue that his worst failures and his greatest accomplishments were both in foreign policy. The Bay of Pigs was a complete disaster; on the other hand, his management of the Cuban missile crisis paints a different picture. Despite tremendous pressure from the military for a more aggressive response, he instead tried to slow the crisis down, and in doing so he opened the space for a diplomatic solution. That was a significant step.

Q. Did serving in the office alter Kennedy’s vision?

A. By 1963, Kennedy was actually starting to make an overture to the Soviets. He made a famous speech in August of ’63 where he began talking about “making the world safe for diversity,” including the co-existence with the Soviets, and a tolerance for the nationalism of newly emerging countries. He slowly began to question the limits of an ideologically driven vision of the Cold War.

He also shifted on civil rights. Kennedy did not want to become involved in the civil rights struggle, especially not in a first term. But in April of 1963, when Martin Luther King and others went to Birmingham and segregationist violence erupted, and the nation witnessed children being hit by fire-hose water strong enough to take the bark off of tree trunks, Kennedy realized he had to engage. And so he went on national television and declared that this was fundamentally a moral question. “It’s as old as the scriptures, it’s as clear as the U.S. Constitution.” Once he did that, he took civil rights out of the realm of political compromise and infinitely deferred negotiation and he elevated it to a matter of principle. You don’t call something a moral question if you are about to cut a piecemeal deal on it. That was a pivotal moment.

Q. The assassination on Nov. 22, 1963, less than three years into his presidency, shocked the nation. How did America and beyond grapple with such a loss, much of it televised?

A. Certainly those tragic images were devastating. There was tremendous sorrow. Many around the world saw him as someone with potential who was capable of shifting away from some of the older ways of thinking about American power. Kennedy was viewed and respected by people like [Jawaharlal] Nehru, by other leaders around the world—in Latin America, for example—as somebody who understood that nationalism, and the desire for these counties to find their own way in the world, was something that had to be taken seriously. With the assassination, Kennedy came to embody the symbol of idealism lost, or betrayed.

Q. With his death, was sixties idealism really lost or betrayed?

A. For some people that outlook changed. To be honest I am not sure it changed the overall direction of American [foreign]policy. I don’t think Kennedy was about to walk out of Vietnam. I don’t see him escaping the mistakes that [Lyndon] Johnson ultimately made there. Historians disagree on this, by the way.

What I do see is a growing recognition on the part of the Democratic Party that some fundamental questions—about inequality, about injustice, about the nature of civil rights—had to be addressed.Lyndon Johnson’s presidency is in many ways the amplification of these trends. Johnson marched into Vietnam wholeheartedly. At the same time,he launched his Great Society program and a determined campaign for civil rights.

One could argue that the seeds of these were ultimately planted in the turn that Kennedy began to make. And Johnson made the most of this by talking about Kennedy’s legacy.

While still caught in the Cold War, Americans were recognizing that these fundamental structural injustices had to be dealt with.

I think that, for all of the mistakes he made, Kennedy captured a certain idealistic moment. [And] it was quite awfully the beginning of a chain of devastating assassinations, be it John Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy, or Martin Luther King, Jr., which seemed to steal the promise of something much, much better.

Q. Do you see parallels between Kennedy and President Obama?

A. There are a lot of parallels. Both entered the White House comparatively young, comparatively inexperienced politically, remarkably articulate and eloquent, capable of inspiring large numbers of people, running on the campaign of change. Obama was not the first person to [talk]about hope and change. Kennedy was talking about the same thing, about a departure from the Eisenhower conservatism, about a version of liberalism in which citizens will be made more active and can pursue these sorts of idealist goals. And yet they are both limited by serious constraints, and they both learn in the process.

The difference is that we will have the full legacy of Obama to evaluate. With Kennedy we are always left with that question of what might have been.

(Interview conducted by Joanna Klimaski and Janet Sassi.)

JFK’s Legacy

Visit soundcloud.com/fordhamnotes/fordhams-michael-latham-on-jfk for interview highlights.