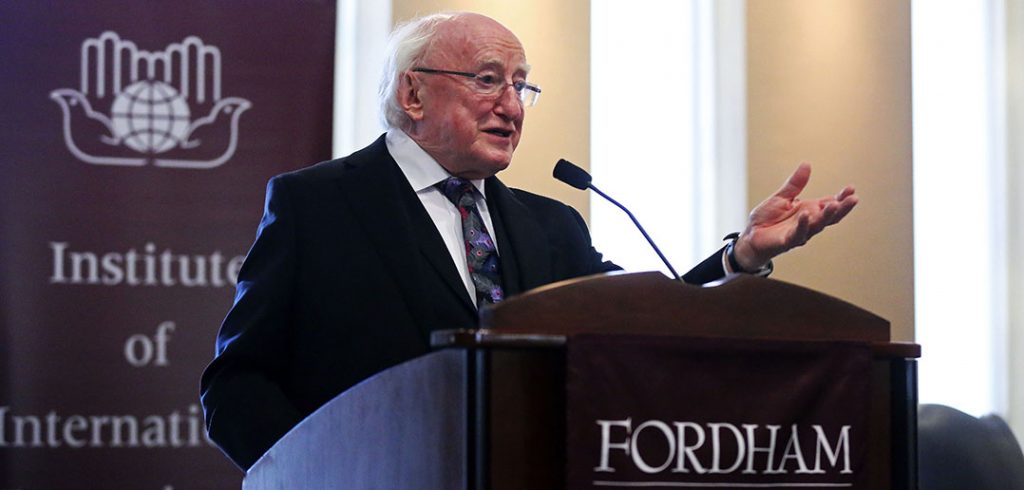

“Universities are challenged in an urgent way by the questions that are now posed, questions that are after all existential, that are of the survival of the biosphere, of deepening inequality, of a return to the language of hate, war, and fear, and the very use of such science and technology yet again for warfare rather than in serving humanity,” he said.

The Sept. 30 lecture was part of the Ireland at Fordham Humanitarian Lecture Series, a partnership between the Permanent Mission of Ireland to the United Nations and Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs. (Watch the full lecture here.)

Higgins, a poet and former professor, said the Irish lost at least one million lives to starvation during the Great Potato Famine and saw more than 2.5 million emigrate. Therefore, the nation holds a collective memory that resonates with today’s crisis.

“We have known what it is to be hungry,” he said in his lecture, “Humanitarianism and the Public Intellectual in Times of Crisis.”

He noted that the Irish famine was editorialized in some newspapers as “an act of God.” The difference today, he said, is that the constant drumbeat of the news cycle desensitizes the listener.

“[Today,] we’ve become accustomed to narratives of how men and women throughout the world as refugees find themselves, through extended periods of time in unsuitable accommodation, confined to forced idleness, without even control over their daily diet,” he said.

Eugene Quinn, director of the Jesuit Refugee Service in Ireland, he noted, has said that children grow up “without the memory of their parents cooking a family meal.”

He lamented that millions of refugees spend years stranded in semipermanent camps around the world, while world leaders discuss the “internationalism and interdependency” of international trade.

“In fact [the conversation]nearly always begins with trade. This has devalued everything, really, in relation to intellectual life, and it has devalued diplomacy very seriously.”

He said that people’s loss of citizenship is so much more than a loss of a homeland. The rights of displaced humans become distinct from the rights of “the citizen.” Without citizenship, refugees lose their inalienable rights as a person, as well as their voice, he said, referencing Arendt.

“To be stripped of citizenship is to be stripped of words, to fall to a state of utter vulnerability with avenues of participation closed off, and thus new futures disallowed,” he said.

Given their past, he said that it falls to the Irish, at home and abroad, to be exemplary to those seeking shelter, especially since it is a crisis that will continue, fostered by climate change and exacerbated by precarious political situations.

“This is a deepening, if you like, of what I call the intersecting crisis of ecology, economy, and society,” he said.

But unlike the welcome that many European refugees received in the wake of World War II, today’s refugees have been shunned.

“The relatively small number of refugees reaching our borders [in the West] has brought forth the type of narrative about ‘the other’ that we in the humanitarian tradition had hoped was assigned to the chronicles of the past,” he said.

“Countries whose citizens have often benefited from international asylum and migratory flows are reneging on their commitments with the aim of discouraging or inhibiting refugees from seeking the international protection to which they are entitled.”

It is here, he said, that public intellectuals and universities must play a crucial role to alter a discourse “soured by hateful rhetoric.” However, he added that today’s charged atmosphere has not made it easier for the academy to exert influence, with some in the community seduced by corporate power, and others complacent with current economic models as the only way forward, he said.

He asked what is being taught in Economics 101 in North America, and questioned how much of it was game theory and how much was real political economy, to say nothing of the coursework’s moral content. He worried that an emphasis on funding beyond the state has had a disjointed effect on the career structure of young scholars.

“I believe public intellectuals have an ethical obligation as an educated elite to take a stand against the increasingly aggressive orthodoxies and discourse of the marketplace that have permeated all aspects of life, including within academia,” he said.

Edward Said said it best when he stated that an intellectual’s mission in life is to advance human freedom and knowledge, he said.

“This mission often means standing outside of society and its institutions and actively disturbing the status quo. Yet it also involves placing a strong emphasis on intellectual rigor and ideas, while ensuring that governing authorities and international intermediary organizations are well-resourced. To quote Immanuel Kant, ‘Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind.’”