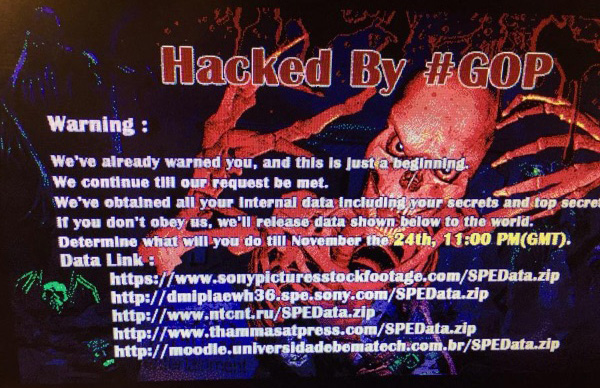

The call came in the early hours of Nov. 24, 2014. “Something really bad is happening here,” Nicole Seligman, the former president of Sony, heard on the other end of the line. “When I turn on my computer I see a menacing red figure and then everything goes dark.”

With each passing minute, emails, copies of unreleased Sony films, executive salary information, and personal information about Sony employees and their families were being stolen and then deleted from Sony’s servers.

It was a terrifying moment, Seligman recalled during a panel at the International Conference on Cyber Security. Moderated by Preet Bharara, U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, the panel included Seligman, David Hickton, U.S. attorney for the Western District of Pennsylvania, and Denise Zheng, senior fellow and deputy director at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

It was not the first time Sony had been attacked, however—in 2011, the PlayStation network was hacked, compromising tens of millions of users’ data. This time around, a Sony executive made the quick decision to shut down the corporation’s entire network.

“We knew something big was happening, and we were aware we were losing a lot of data, so we immediately went offline,” Seligman said. “As a result, half our servers survived. Otherwise everything would have been gone, because this was an attack in which they were stealing data and then executing a command to destroy.”

Going dark spared the company further intrusion, but left everyone with the resounding question of, “Now what?” No one had access to email or voicemail. Calendars and contacts were lost. People were “sitting at their desks trying to do their job with a pen and paper,” as one staff member was widely quoted immediately after the hack.

Logistical issues were just one of the lessons Seligman said the corporation learned from the 2014 hack. She urged that all companies have business continuity plans in the event that networks become suddenly unavailable. Back up information on other servers, she said, or print files and keep hard copies.

In addition, companies ought to establish clear lines of authority with regard to company networks. If a hack occurs, Seligman said, you do not want to spend precious minutes trying to figure out who is the right person to make the call about going offline.

Similarly, there must be frequent conversations about cybersecurity at the highest levels of the company.

“If you have trade secrets and corporate information, how do you secure it? What kind of threat do you assume—a hacktivist, or some kid sitting in a basement?” Seligman said. “You need to do a cost/benefit analysis about what data you need to guard, how much you’re going to spend to secure it, and how much that will interfere with operations.”

Most important, Seligman said, is to establish ongoing relationships with law enforcement. In Sony’s case, the FBI not only responded to the immediate threat, but also helped guide the corporation through the recovery process.

“It’s very lonely when you’ve you been attacked and you’re offline,” she said. “There is an assumption that with just a little bit of money and savvy you could’ve prevented an attack. So you’re in a position where you’re a victim, but somehow you’re also the wrongdoer.

“In our case, the FBI stepped into that void and acknowledged that we were the victim here.”

Follow Fordham News for coverage of ICCS 2016.