The two-day summit, which took place at the McGinley Center on the Rose Hill campus, drew over 250 attendees as well as participants who joined through an online broadcast.

On Day 1 of the conference, Michele Burris, associate vice president in the Office of Student Affairs at Fordham, highlighted the need to address sexual violence on college campuses all across the country. She touched on the tenets of Jesuit education as a call to action, in particular St. Ignatius of Loyola’s desire for “something greater”—magis.

On Day 1 of the conference, Michele Burris, associate vice president in the Office of Student Affairs at Fordham, highlighted the need to address sexual violence on college campuses all across the country. She touched on the tenets of Jesuit education as a call to action, in particular St. Ignatius of Loyola’s desire for “something greater”—magis.

“We will not accept mediocrity when it comes to how people are treated, when it comes to the respect of each and every person’s body, and when it comes to ending sexual violence,” Burris said.

Burris worked closely with Katie Koestner, the executive director of the Take Back the Night Foundation, to sponsor the conference and bring like-minded activists together from around the globe. The summit featured a keynote by Margaret Huang, interim Executive Director of Amnesty International USA, who has advocated for human rights and racial justice for more than two decades.

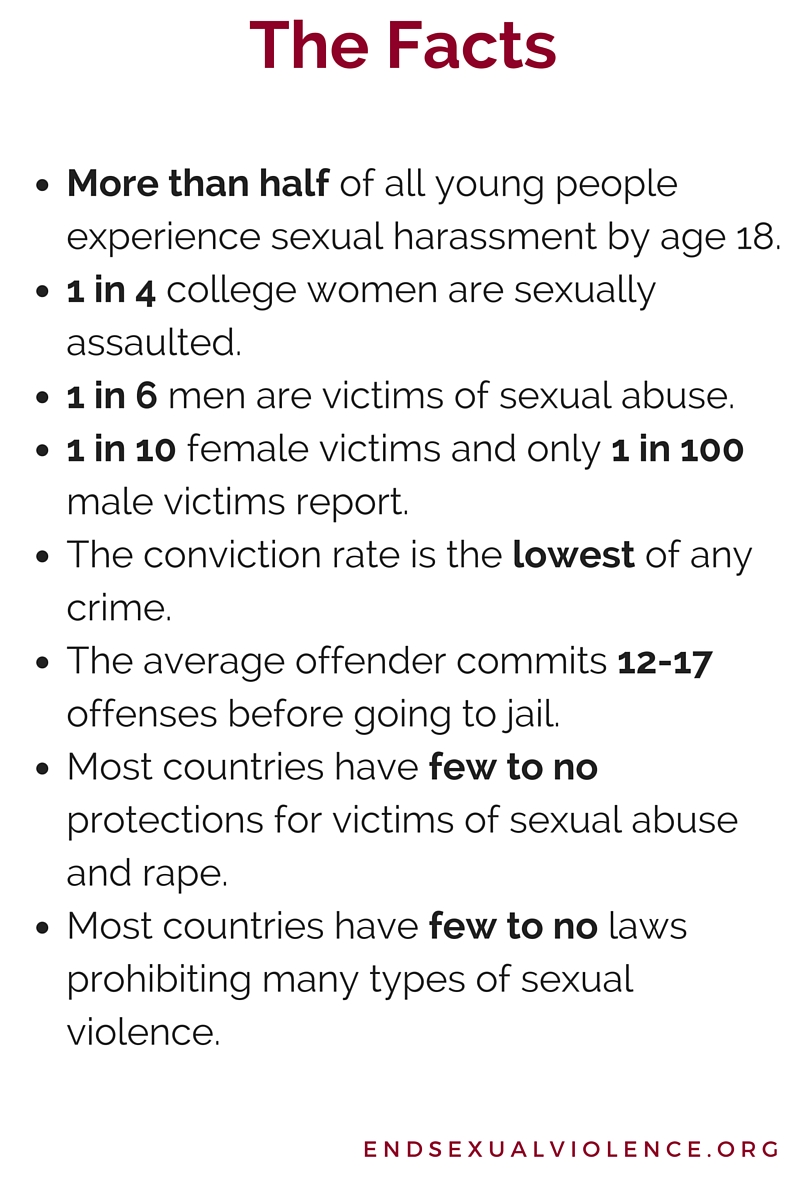

Huang stressed that women’s rights are at the heart of Amnesty International’s work in protecting human rights, and that one of the biggest barriers to women’s freedom is sexual violence.

“One of the greatest barometers of a society’s freedom is whether women are fully free and empowered,” Huang said.

In the United States, Amnesty International has worked with Native American and Alaskan native women, who are two and a half times more likely to be raped than non-indigenous women, said Huang. She also said that 86 percent of those who rape native women are non-native men.

Particularly appalling is the fact that, in the past, American laws have prohibited tribal courts from prosecuting non-native men, Huang noted.

In 2007, Amnesty published a groundbreaking report, “Maze of Injustice,” which included contributions from indigenous women’s rights leaders from across the country. With the help of this report and advocacy from Amnesty International, Congress passed the Tribal Law and Order Act in 2010, which grants tribes the jurisdiction to prosecute non-native accused rapists in tribal courts.

While this is a major step forward, Huang stressed that there is still much to be done in countries around the world, including in India, Burkina Faso, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), among others.

According to Huang, Burkina Faso ranks among the top 10 countries with the highest rates of child marriage, where one in every two girls will be married before the age of 18. In fact, on the African continent forced marriage affects 15 million girls each year, with one in nine girls marrying before the age of 15.

“Child brides are at a much higher risk of suffering from dangerous complications in pregnancy, HIV, and domestic and sexual violence,” Huang said.

In India, rape is the fastest growing crime, with a startling increase of 873 percent in cases reported between 1971 and 2011, according to the National Crime Records Bureau, said Huang. Women from low-income communities there “face shame and stigma when reporting rape, which makes it even more difficult for them to seek justice.”

In response, Amnesty International India has launched a campaign to ensure that women who choose to report sexual violence can do so safely, with dignity, and without prejudice through the website www.readytoreport.in.

The two-day event featured more than 100 presenters and performers taking a collective stand against sexual violence of all kinds, including dating violence, campus sexual assault, child sexual abuse, domestic violence, and trafficking.

—Angie Chen, FCLC ’11