Twenty years ago, if Kabba Williams were to imagine standing before a group of New York City college students discussing education, it would have seemed like a cruel fantasy. Back then the only skill the 7-year-old West African had been taught was how to fire an AK-47.

But as he now knows firsthand, “Education can take you everywhere.”

On April 9, Williams, who was one of the youngest child soldiers rescued during Sierra Leone’s 11-year civil war, addressed a group of undergraduate political science students shortly after they were inducted into Fordham’s chapter of Pi Sigma Alpha, the national political science honor society.

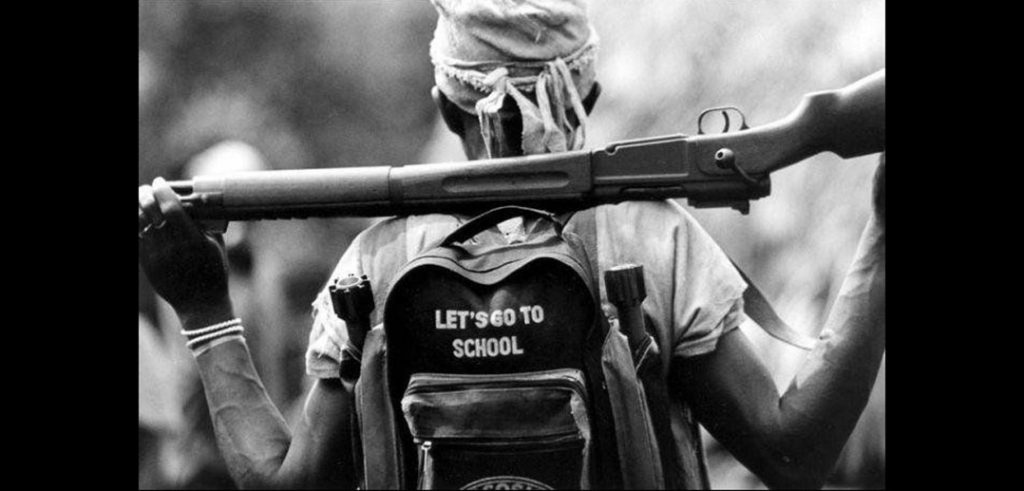

In his keynote address, “Conflict-Affected Youth: Education and Paths to Peace,” Williams offered his harrowing history as testament to the power of education.

Photo by Bruce Gilbert

One day, when he was about 7 years old, Williams returned home from a neighboring village to find that the rebel Revolutionary United Front (RUF) had attacked. Bodies lined the roadways, homes were ablaze, and Williams’ mother had vanished.

The rebels kidnapped the surviving children—Williams among them—and took them to the RUF base for war training.

“The first exposure I had to any education was the kind that no child should ever receive,” said Williams, who is now an advocate for education and the reintegration of ex-combatant youth. “Instead of books and papers, I was given a gun and taught how to run and hide with it.”

The RUF forced Williams and the other child soldiers to murder, torture, and commit sexual violence. Often, the children were drugged so that they would be more controllable. The drugs, Williams said, made him “mad” and “fearless.”

Williams escaped the RUF after six months, only to be captured by the Sierra Leone Army (SAL) and forced to fight for another three years. He was about 10 when a UNICEF representative found him and connected him with the charity Children Associated with War.

The battle wasn’t over, however. Rescued child soldiers underwent a process of “disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration” to help them rejoin society. But the years of psychological damage—compounded by the stigmatization they encountered in their former communities—left many former child soldiers unemployed, drug addicted, and homeless.

“We were just left—the lost children of Africa,” Williams said.

In the end, what saved him was his ardent desire for an education, Williams said. He attended school for the first time at an orphanage in an SOS Children’s Village and fell in love with learning. He felt such an urgency to catch up to his peers that he would trade his meager food rations for extra tutoring.

“I admired the other kids,” he said. “Sometimes when I saw them reading I thought it was magic.

“Despite all the obstacles, I was determined to be educated because I knew the power of education. It is the best legacy you can ever attain in this world. No one can take it from you.”

Today, Williams is a college graduate and an advocate for the tens of thousands of children who are forced onto the frontlines. He has served with the African Youth Parliament, Amnesty International, and the United Nations.He urges his audiences to understand that although child soldiers have committed grave crimes, they were as much victims of war as they were perpetrators. Sadly, he said, this is a message the world struggles to understand. (Williams himself was almost barred from entering Canada for a conference because he was labeled a war criminal.)

“What you give young people is what they give back to the country,” Williams said. “If you give a child criminality, then you’ll find we have criminals running the country.”

The event was sponsored by the Department of Political Science, the Fordham College at Rose Hill Dean’s Office, and the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs.