In 1980, French philosopher Gilles Deleuze and psychoanalyst Félix Guattari revolutionized philosophical thinking in the 20th century with the acclaimed book, A Thousand Plateaus.

But what parallels can we draw from the landmark text in a global society?

Through a series of lectures from Dec. 10 to Dec. 15 at Tsinghua University in Beijing, China, Nicholas Tampio, Ph.D., an associate professor of political science, examined Deleuze and Guattari’s pioneering theories through such a political lens.

Tampio, who specializes in the history of political thought, contemporary political theory, and education policy, spoke of Deleuze’s political vision and how it sheds light on think tanks and intercivilizational dialogue.

Xia Ying, a philosophy professor at Tsinghua, invited Tampio to speak at the leading research university founded more than 100 years ago. Stephen Freedman, provost of Fordham University, said many Fordham faculty have scholarly activities with key universities in China—which is an important priority for Fordham.

“For each lecture, I talked for about an hour, and then everyone asked for clarifications or shared their thoughts, for instance, on how to diagram Chinese political thought,” said Tampio, author of Deleuze’s Political Vision (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015).

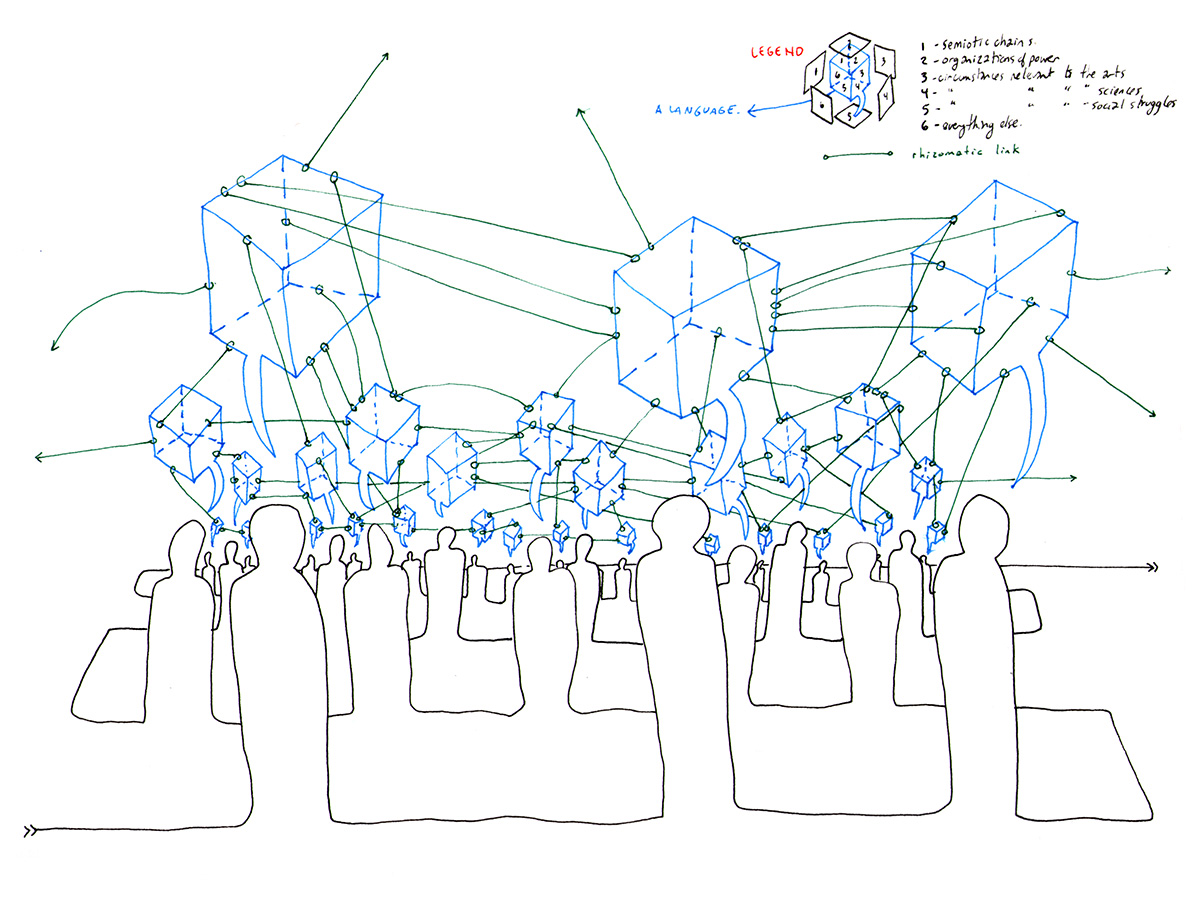

Among Deleuze’s most thought-provoking concepts was his model of the rhizome. Based on the botanical rhizome or “mass of roots” which spreads from a tree, the theory is akin to political multiplicity.

“On one hand, the goal of the lectures was to share my knowledge about Deleuze, but on the other hand, I wanted to discuss the relevance of Deleuze’s ideas in the Chinese context,” said Tampio.

Though China follows capitalistic economic principles and operates as a one-party system, Tampio said he wanted to foster discussions about Deleuze’s philosophical approach amid China’s evolving role in international politics and business.

“It was exciting to see the audience in China thinking about the ideas of the rhizome, and what it would mean to have a multi-polar world where there is no tree trunk of centralized power but where countries have to interact to address shared concerns,” he said.

Tampio, who had never been to China before, said Chinese citizens tend to be more sympathetic to the notion of centralized authority because of their own political system.

“In the West, we have a vibrant public sphere and civil society where people are free to disagree with the government,” he said. “But nearly everyone I met in China spoke English and was interested in talking. China does not have the same tradition of free speech; at the same time, the Chinese I met were curious and open to learning and sharing ideas.”

In the process of sharing knowledge about Deleuzian liberalism, pluralism, and comparative political theory, Tampio said he returned to America with new perspectives.

“China is an economic powerhouse that wants to play a larger role on the world stage, economically and politically,” he said. “We have to take China and Chinese political thought seriously.”