Celia Fisher, Ph.D., knew she was onto something in 1997 when she asked Joseph M. McShane S.J., president of Fordham who was then dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill, to fund a series of faculty seminars around the topic of ethics. In 1999, the success of those seminars led to the creation of the Center for Ethics Education.

Twenty years later, Fisher, the Marie Ward Doty University Chair in Ethics, says she’s still amazed at what the center has accomplished. The center, which received initial funding from the National Institute of Health and Fordham’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, currently oversees educational programs on the undergraduate, graduate, and post-graduate level. It has produced over 200 publications and has received a total of $11 million to conduct research supporting the rights and welfare of vulnerable populations. For the past eight years, it has also administered the HIV and Drug Abuse Prevention Research Ethics Training Institute.

Interdisciplinary From the Start

Fisher said one of the center’s greatest points of pride has been its interdisciplinary focus.

“The center’s success was built on the support, encouragement, and involvement of faculty of all the different schools and programs at Fordham,” she said.

“To be able to put all that together with the support of an interdisciplinary faculty, advisers, and teachers has been an incredibly wonderful experience.”

From the very beginning, Fisher, whose background is in psychology, has had two associate directors hailing from the theology and philosophy departments. Curran Center for Catholic Studies Director Christina Firer Hinze, Ph.D., represented theology when the Center for Ethics Education started and was followed by Barbara Andolsen. Currently, the position is held by theology professor Thomas Massaro, S.J.

Michael Baur, Ph.D., an associate professor of philosophy and adjunct professor of law, joined in 1999 as associate director and never left. It helps, he said, that he is “constitutionally built” to be interdisciplinary.

“For those who are predisposed to think beyond boundaries, the center provides a huge playground of full opportunities to think creatively about different disciplines,” he said.

“The center has made it really easy for me to start conversations with people I never would have spoken with about economics, psychology, biology, and neurosciences.”

In 1999, Baur recalled, the goal of the center was to create a space for crossing boundaries to address ethics and being open to whatever came along as a result. The interdisciplinary minor in bioethics, which was first offered to undergraduates in 2013, is an example of how the center has evolved to meet the needs of students.

“We already had the goodwill and the communications among different faculty. We didn’t have to reinvent the wheel,” he said.

Debating Issues of the Times

When it comes to public programming, the center, which kicked off its 20th-anniversary celebration with a March 7 lecture titled “Ethics and the Digital Life,” has hosted events dedicated to nearly every thorny issue debated in the United States today.

Its first public event was an April 2000 workshop titled “The Ethics of Mentoring: Faculty and Student Obligations.” In a lecture four years later, Christian ethics professor Margaret Farley, Ph.D. weighed in on the use of human embryonic stem cells in research. The drug industry was the focus of a 2005 forum, “Bio-Pharmaceuticals and Public Trust,” and in 2012, the center co-sponsored “Money, Media and the Battle for Democracy’s Soul,” where former Senator Russ Feingold issued an ominous warning about the role of money in politics.

In 2013, a conference tackled the uncomfortable reality that the United States accounts for about 5 percent of the world’s population, but is home to nearly a quarter of the world’s prison population. Four years later, the center’s decision to co-sponsor “In Good Conscience: Human Rights in an Age of Terrorism, Violence and Limited Resources,” proved prescient, with the actual lecture coming two weeks after terrorist attacks in Brussels.

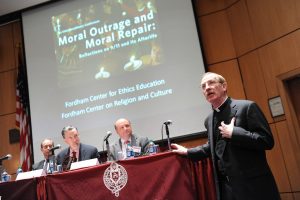

For Fisher, one of the most emotional events was “Moral Outrage and Moral Repair: Reflections on 9/11 and Its Afterlife,” a daylong conference co-organized with Fordham’s Center on Religion and Culture in April 2011.

“It was so moving. We had clerics from all different religions, we had philosophers talking about forgiveness, all sides of it. We had survivors and families of survivors. It was such an emotional experience,” she said.

A Flexible Master’s Program

The center’s efforts are not confined to lectures and panels. In 2009, at the suggestion of former Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Dean Nancy Busch Rossnagel, Ph.D., the center began offering a Master of Arts in ethics and society under the direction of Adam Fried, Ph.D, GSAS’ 13, 17. It is now overseen by Rimah Jaber, GSAS’ 16.

Yohan Garcia, GSAS ’18, one of the program’s 57 alumni, recently accepted a position as national formation coordinator for the Archdiocese of Chicago’s Pastoral Migratoria (Migration Ministry) program.

A native of Mexico who moved to the Belmont neighborhood in 2003, Garcia earned an undergraduate degree in political science from Hunter College in 2015. In 2013, he attended a spiritual retreat and realized he wanted to incorporate his faith into his studies. As a Fordham master’s student, he took classes such as Natural Law (at the Law School); Race, Gender and the Media; and Introduction to Thomas Aquinas. Today, he’s able to apply what he learned in each of those courses to his work around immigration.

Although he’s only just started his job in Chicago, he’s already considering applying to Ph.D. programs.

“When it comes to issues like immigration, there’s no easy solution,” he said.

“We all have a different idea of the common good, but at the end of the day, as a society, we have to work toward a common goal that will benefit all of us. Listening is a great skill and a gift to have when it comes to this issue.”

HIV Research Training

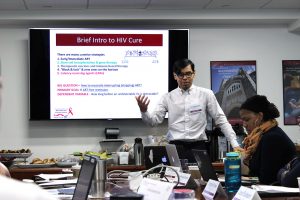

Faith Fletcher, Ph.D., an assistant professor of health behavior at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, completed training with the HIV and Drug Abuse Prevention Research Ethics Training Institute (RETI) in 2016. The institute, which is funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, has to date provided over 42 early career professionals in the social, behavioral, medical, and public health fields with an opportunity to gain research ethics training.

A native of Thibodaux, Louisiana, who was one of the first students to pursue a bioethics minor as an undergraduate at Tuskegee University, she has focused on the ethics of engagement with African American women living with HIV.

“Before coming to the research ethics training institute, I had training in both bioethics and public health, but I really struggled with finding the academic spaces, and even the language to combine these disciplinary areas,” Fletcher said.

“The institute is definitely the highlight of my academic career.”

Because she works with marginalized populations, Fletcher said her biggest challenge is avoiding situations that jeopardize the safety of them or researchers. It’s a real issue, as researchers engaged in qualitative research sometimes conduct interviews in vehicles, bars, and other unorthodox places to make sure the people they are interviewing are not further stigmatized.

“What I’ve learned from the training is we have to rely on research participants as research ethics experts, because they have these daily experiences with stigma, and are skilled at navigating and circumventing stigma. These are the individuals we have to go to as we’re designing our research ethics protocols,” she said.

It’s humbling work, and Fletcher said the women she’s interviewed have taught her much about resiliency.

“I’ve learned so much about the way that they’re able to navigate through society despite high levels of stigma and stress, and the way they’ve coped with it, risen above it, and not allowed it to define them,” she said.

“I’m thankful for them allowing me into their spaces, because not only does it enhance my research, but I’ve grown personally from their stories.”

Protecting the rights and welfare of vulnerable populations has been a common theme running through the centers’ NIH-sponsored research. For instance, Fisher was the principal investigator on a 4-year series of studies designed to reduce the burden of HIV among young sexual and gender minority youth. The results of one of these studies were published in the journal AIDS and Behavior.

In 2014, based on a project supported by the Fordham’s HIV, Research Ethics Institute, Cynthia Pearson, Ph.D., was awarded a grant, along with Fisher, to adapt a culturally specific ethics training course for American Indian and Alaska Natives populations. Fisher also led a study in 2006 to assess and develop procedures to enhance the capacity of adults with mild and moderate mental retardation to provide informed consent for therapeutic research; the results were published in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

A Shared Dedication to Social Justice

Going forward, Fisher said she wants to expand the involvement of the faculty and alumni in center programming, recruit more international students, and establish a research center on health disparities among marginalized populations.

Since its beginnings, the Center has been grounded in Fordham University’s commitment to intellectual excellence, human dignity, and the common good. The success of the center, she said, is due in no small part to the breadth and depth of Fordham’s faculty dedication to these ideals.

“Faculty, students, and administrators share this dedication to social justice and helping others that just implicitly supports what we’re doing. So, when we reach out to faculty, they are already providing students with the tools for critical and compassionate engagement in creating a just world,” she said.

“They may not do work in ethics per se, but the way they think, because they’re at Fordham, they are committed to caring for the least among us.”