Just before his untimely death in 2014 at the age of 40, Powell gave part of his archives to Fordham. His book collection, known affectionately by friends as the Morgan Library, arrived shortly after he died.

The collection buttressed the late historian’s already substantial contribution to the Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP). The archives include material from his two primary interests: African-American history and local ecology.

Patrice Kane, head of archives and special collections at Fordham Libraries, said that despite Powell’s lack of academic credentials, he was familiar with and understood archival standards. She said what distinguished him from other amateur historians was that he wasn’t fixated on a particular period.

“Good historians are born, they’re not made,” said Kane. “He had the ability to make history come alive.”

In the oral history he gave for the BAAHP, the Jamaican-born Powell talked of a youth spent Harlem after his mother immigrated to New York. The family eventually moved to the Bronx. Though he was born abroad, he said he identified as an African American. He said he attended a good public grade school and avoided trouble in high school. However, he said his mother was unable to co-sign on a loan for the 17-year-old to go to college.

“I was too young to sign my own financial papers, and I was not able to establish independence because I wasn’t independent,” he said. “So that set up a whole series of events and circumstances that the whole rest of my life is going to be a consequence of, because that is a huge thing.”

Powell began educating himself and ferreting the stacks of the Schomburg Center, the Bronx Historical Society, and many used bookstores. Much of the material donated to Fordham is not from an original source, but the thousands of copies of receipts, photos, maps, and articles, represent diverse sources pulled together for the free tours he gave to Bronx residents.

“Not everyone thought of linking African-American history to the rivers, waterways, and parks,” said Mark Naison, PhD, professor of African and African American studies. “The tours he led were totally original.”

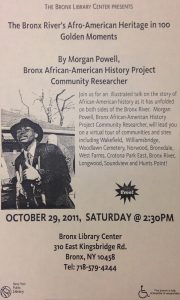

Along the way, Powell became as much of an activist as he was a tour guide. He lobbied for an African-American history collection at the New York Public Library’s Bronx Library Center and for a new master plan at Crotona Park. The latter effort included a letter, which he said he signed, “Your friend of mid-Bronx parks and critic of failed bureaucracy, Morgan Powell.”

His efforts still inspire visitors to the archive and fellow activists that knew him, such as Ajamu Brown, a Brooklyn activist working on food justice issues.

“We talked about the challenges of people of color who do this kind of work,” said Brown. “From him I learned about some of the important people who were involved, and (I learned) about thinking holistically about these problems.’’

As a devotee of history who never charged for his tours, there was little money left behind for a proper burial. But friends raised more than $17,000 to have his remains interred at the historic Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. Brown said that at a memorial service there was a “cross section of scholars, activists, and farmers.”

“It wasn’t like he wasn’t getting paid to do this,” said Brown. “We need more people who are willing to investigate this history and not just in the Bronx. Too many get written out of history.”

In the oral history project Powell was asked why he stayed on in the Bronx. His answer reflected his views on higher education.

“Perhaps [the reason]I care about the Bronx is maybe I was forced into empathy with the Bronx… Maybe it is because I could not get on that educational escalator, so that I could reach my own educational potential… [and become]someone who now has that masters degree in whatever I would have pursued… and gotten those various jobs out of college and moved out to Westchester or elsewhere as so many of my similar others have. Maybe that is why I am still in the Bronx. I think that’s an enormous part of it.”