In the case of “The World’s Oldest Church,” a new book by Michael Peppard, PhD, the art can be found in a third-century house-church in Dura-Europos, a walled city along the banks of the Euphrates River that once stood in present day Syria.

For Peppard, associate professor of theology, the book, published this month by Yale University Press, is an ambitious attempt to combine theology and art history to tell a new story about the oldest known house of Christian worship.

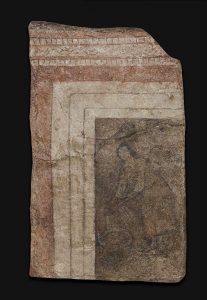

In addition to offering an up-to-date compendium of scholarship on the building, Peppard makes the case for a completely different understanding of three images that were found there: one of David and Goliath, one of a procession of women, and one of a woman at a well. All three were excavated in the 1930s and are housed at the Yale University Art Gallery.

Peppard s aid he is most excited about the image of the woman at a well. Almost everyone assumes that she is the Samaritan woman from the Gospel of John and that she symbolizes baptism, as represented by the “living water” of the well. Peppard said that the painting is actually a portrayal of the annunciation, “when Mary is told she is going to bear a son as a virgin.”

aid he is most excited about the image of the woman at a well. Almost everyone assumes that she is the Samaritan woman from the Gospel of John and that she symbolizes baptism, as represented by the “living water” of the well. Peppard said that the painting is actually a portrayal of the annunciation, “when Mary is told she is going to bear a son as a virgin.”

“If the image is the Virgin Mary, then not only is it probably the earliest datable image of Mary, but it’s also going to change the way we interpret the artistic program of this church, and maybe change the way we think about what they thought they were doing there,” Peppard said.

The image of women processing has likewise been misidentified, he said, as a funeral procession when in fact it’s a wedding procession.

Taken together, the paintings illustrate that these Christians emphasized empowerment, healing, marriage, and incarnation more than death and resurrection. This isn’t surprising, he said, because very few images of the Crucifixion exist from this time.

“In this earliest Christian church, we don’t have any imagery of the resurrection. I think they certainly believed in it, and that it was part of their faith in who Jesus was and what it meant to be a Christian, but it’s a matter of emphasis,” he said.

“So what are they emphasizing if they’re not emphasizing the cross and resurrection in this baptistery? They are emphasizing imagery of marriage, which is very common in Syrian Christianity—that becoming a Christian was like getting married to Christ and having a covenant with God.”

The story of Dura-Europos illustrates how Christianity evolved differently in different regions, he said. In the year 300 A.D. Christians were spread as far east as Dura-Europos and as far west and north as present day Morocco, Spain, and France. The Roman emperor Constantine had not yet converted to Christianity (which would make it the mainstream faith in the Roman empire), and communication and travel were still difficult.

Peppard also wondered why the baptistery of this church would feature a fairly grim image of David and Goliath. It might be because, at the time, Dura-Europos was the last outpost before one crossed the river into Persia and the Sasanian Empire, the most fearsome empire next to the Roman Empire.

“The Goliath image is in the style of a Persian warrior, so they’re styling their enemy in the guise of their real enemy in the world. This is part of their militaristic imagination. They feel threatened by this goliath across the river, so they imagine their initiation as Christians as empowering—gaining the power of David so that they can, when they need to be, be ready for the battles in their life,” he said.

“This is an urban outpost in the middle of nowhere in Eastern Syria, in the desert perched above the Euphrates. Let’s not presume they were like Christians from 2,000 miles away who they’d never heard or talked to.”