Elizabeth Johnson, C.S.J., whose deep, varied, and acclaimed scholarship has laid the groundwork for generations of theologians to come, was celebrated by hundreds at a standing room only event at the Lincoln Center campus on April 30.

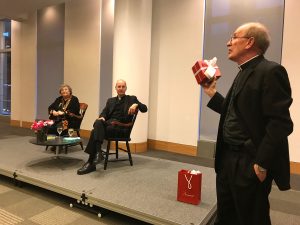

In a wide-ranging, occasionally raucous interview, Sister Johnson, a distinguished professor of theology who joined the Fordham faculty in 1991 and is retiring this year, talked with James Martin, S.J., editor at large of America magazine.

Father Martin credited Johnson’s scholarship with changing his life.

“On behalf of all of us nonprofessional theologians, and non-academics like myself, thank you for doing so much for making contemporary theology, feminist theology, and especially Christology so accessible to the general reader,” he said.

Their conversation revolved primarily around Creation and the Cross, (Orbis, 2018), Sister Johnson’s 11th book, which she recently discussed for a Fordham News podcast.

Bidding Adieu to Satisfaction Theory

Sister Johnson explained how the goal of the book is to help ease the satisfaction theory of atonement into retirement. The idea, which was promoted by St. Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury, in the 11th century, in a tome titled Cur Deus Homo, was an attempt to answer a fundamental question for Christians: Why did God take the form of a human being, in Jesus Christ, and then die?

“The answer was, in order to pay back to God a certain satisfaction for the dishonor that human sin has caused,” she said.

“[According to Anselm], sin dishonors God, and we owe a debt. We human beings can’t repay that debt because the person we have offended is infinite, and therefore God became a human being and took on the debt and paid it back through death.”

Over time, however, others used this theory to explain how God is angry and vengeful, and “needed the bloody death of an innocent person in order to forgive us,” Sister Johnson said.

“That sounds very bold and bald, but that is what it has come down to over the centuries,” she said, noting that contrary to traditional ministry, Jesus was not born to die. His death, she said, was a result of his dogged, uncompromising preaching and the difficulties he created for the Roman Empire.

A Powerful Alternative

The solution, she said, is accompaniment theory.

“In Jesus, we have God with us, who has gone into the worst kind of death, in order to be with every single creature that dies, with the hope for something more. With that, we open up into the rest of creation,” she said.

Father Martin offered his own view of St. Anselm’s text. “Having read Cur Deus Homo way back in philosophy, [satisfaction theory]really bothered me, he said. “To have a professional theologian put it in its place and as you say, ‘give it a well-deserved retirement,’ was a relief for me, because I think it’s a burden for a lot of people.”

Sister Johnson noted that the idea has been questioned before. St. Thomas Aquinas first pointed out the absurdity of human kind’s salvation being contingent upon the death of an innocent man, and even Pope Benedict wrote disapprovingly of it when he was a Cardinal.

She said the key to “accompaniment theory” is the idea of deep incarnation, and a closer examination of the word “flesh,” as featured in the Gospel of John 1:14: “The Word became flesh and made His dwelling among us,” the scripture says.

According to Sister Johnson’s research, she said, the word flesh refers not to human beings, but to “what is vulnerable, finite, transient, and subject to death and pain.” She noted that the first appearance of the word goes all the way back the book of Genesis, in the story of Noah and the Great Flood.

“If you track this through the Bible, it become a very powerful tradition that we’ve missed,” she said.

Love the Cockroach

Sister Johnson said that embracing accompaniment theory means one should look to all creatures as kin, and not consider yourself as yourself as the pinnacle of a pyramid of life. This led to the most humorous moment of the evening, as an audience member wondered in the Q&A session, how could they possibly look at cockroaches as kin?

“Truthfully, you have to admire the cockroach. It has tremendous staying power, and it has the power to adapt to all kinds of place, including your kitchen,” she said, adding that loving them does not mean letting you run roughshod over you.

“Pope Francis writes at the end of Laudato si that ‘Every creature will be resplendently transfigured and with us, enjoying the beauty of God.’ So I think the cockroaches will be there too.”

Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, called Sister Johnson a source of great inspiration, challenge, and a great love of God. And like God, he said, she is hard to categorize.

“It is for the benefit of the church that you’re hard to nail down, hard to categorize. You dance with the questions, and therefore you play with God, and God plays with your heart, and that allows you to do all you have done to become the iconic feminist theologian of American theological history,” he said. “for which we are deeply grateful.”

Proceeds from a reception earlier in the evening reception supported the Elizabeth Johnson endowed scholarship, which supports female Ph.D. candidates on the verge of finishing their dissertations.