As the General Assembly of the United Nations meets this week to discuss a full agenda of international matters, the impact of the UK’s decision in June to leave the European Union is likely to be a topic of concern, particularly among its closest neighbors.

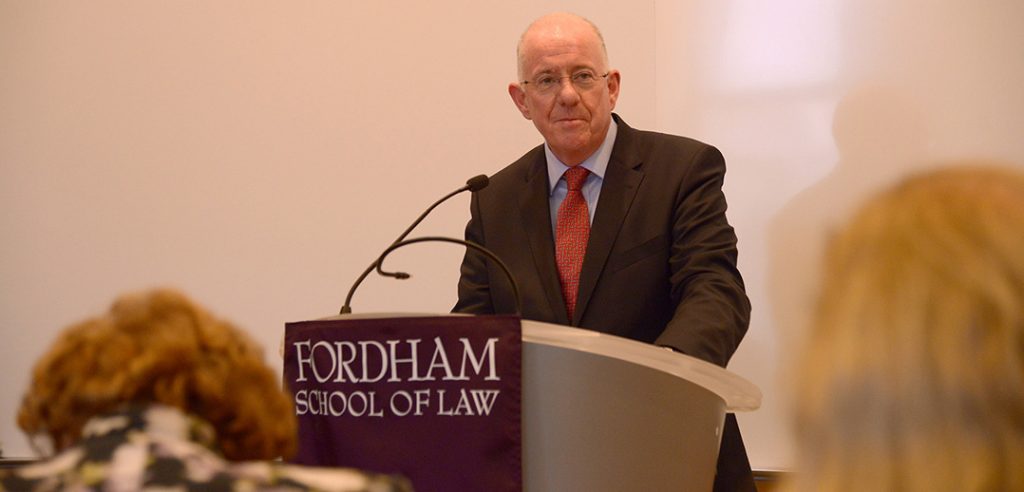

The government of the UK’s nearest neighbor, Ireland, may prove to be one step ahead of its fellow EU member states in reckoning with the effects of Brexit. During an address given at Fordham Law School on Sept. 19, Ireland’s Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade Charles Flanagan told an audience of around 100 that his country had been preparing for a possible Brexit vote for a year.

“Expert reports were commissioned. All relevant government departments were asked to examine the possible impacts,” Flanagan said. “State agencies, business representatives, trades unions, and other stakeholders were consulted with and kept informed on the government’s approach.”

That approach stemmed from the country’s hope that the UK would stay with the EU. While the outcome of the vote disappointed Ireland, the government honors the process through which it was reached.

“Ireland was clear that we wished the UK to remain in the EU, as our analyses had shown that such an outcome best served our strategic interests,” Flanagan said. “However, by a narrow margin the result was otherwise, and the UK electorate voted to exit. The decision was a democratic one and we respect that.”

As the UK moves forward with its exit from the EU, the Irish government has reaffirmed its commitment as a faithful member of the EU and the Eurozone. Flanagan said that Ireland will continue to serve as a gateway to the EU for foreign investors. In speaking of Ireland’s contiguous border with Northern Ireland, Flanagan enumerated the particular challenges in the context of the UK region’s turbulent history with its southern neighbor.

“When the UK leaves the EU, Northern Ireland will be the only region in Britain which shares a land border with another EU member state,” Flanagan said. “One of our key concerns raised by Brexit is a return to a hard or fortified border dividing north and south.”

Flanagan went on to say that the reinstating of a hard border would negatively affect cross-border trade and economic activity. However, more serious would be the symbolic effect of resurrecting historical divisions.

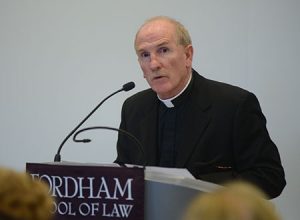

Despite the challenges ahead, Flanagan sounded an optimistic note when he told the audience that Fordham values can inspire politicians and government officials during this uncertain time.

“As the European Union and Ireland prepares for a challenging period ahead, there is much to learn from the Fordham ethos,” Flanagan said. “Above all, there will be a need to apply what is emphasized in this University in terms of critical thinking and creative problem-solving.”

Left to right: John Feerick ’61, professor and former dean of Fordham Law School; Charles Flanagan, Ireland’s minister for foreign affairs and trade; Anne Anderson, ambassador of Ireland to the United States; Barbara Jones, counsel general of Ireland; Joseph McShane, S.J., president of Fordham University. Photo by James Higgins.

Left to right: John Feerick ’61, professor and former dean of Fordham Law School; Charles Flanagan, Ireland’s minister for foreign affairs and trade; Anne Anderson, ambassador of Ireland to the United States; Barbara Jones, counsel general of Ireland; Joseph McShane, S.J., president of Fordham University. Photo by James Higgins.