To heal a sick person, you need the proper diagnosis, the right treatment, and a compliant patient.

When it comes to sexual abuse, the Catholic Church is no different, said Nuala Patricia Kenny, MD, SCH.

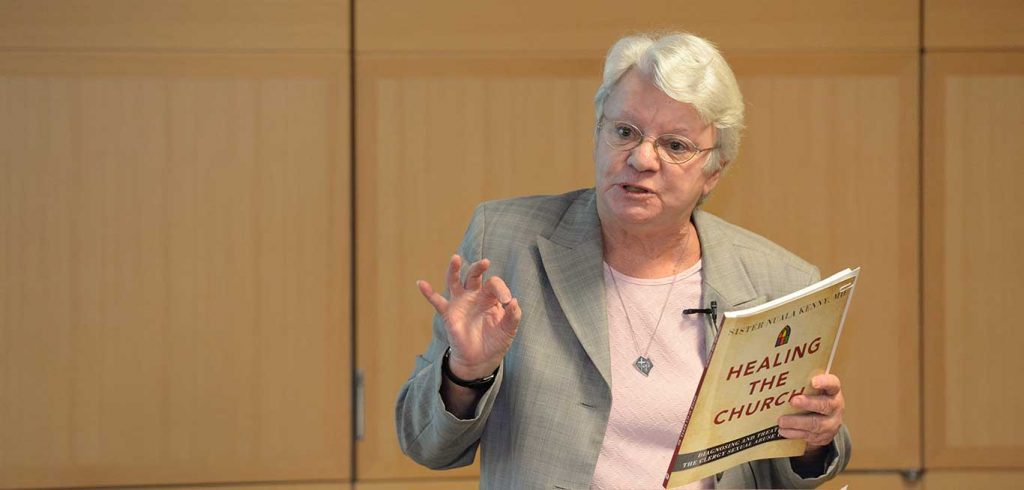

“I love the church. I do not love when members of the church have not been witnesses to the healing and reconciling mission of Jesus, especially in relation to the protection of children,” said Sister Kenny, who spoke on March 10 at Fordham’s Lincoln Center campus.

“I’ve met so many Catholics who still don’t want to talk about this, who believe that any conversation about this is disloyal,” she said. “Ridiculous. When you see evil, you have to in fact begin to grapple with it if you are going to turn it towards good.”

Her talk, “Healing the Church: Some Systemic, Cultural and Legal Considerations” was sponsored by Fordham Law School’s Institute on Religion, Law & Lawyer’s Work.

It relied on many of the revelations she shared in her book, Healing the Church: Diagnosing and Treating the Clergy Sexual Abuse Scandal (Novalis, 2012), but with updates to reflect developments such as the Oscar-winning film Spotlight.

Sister Kenny’s experience with sexual abuse in the clergy dates back to 1989, when an extensive pattern of abuse was revealed at the Mt. Cashel Orphanage in St. John’s, Newfoundland. A pediatrician by training, she called her involvement with the official investigation more painful than the end-of-life care she’d done with children.

In some ways, the movies Doubt and Spotlight exemplify the ways society has shifted from denial of the problem to focusing on the individual to focusing on the systematic failures of church hierarchy. She divided the modern day phenomenon in the United States into three categories dating back to 1984, while noting that the issue is has never been a new one.

“You can’t say this is a recent event when it was addressed at the Council of Elvira in 306. The first council of the church in which there is a discussion about the morality of clerics involving themselves with young boys,” she said.

“You don’t like that one? How about the Book of Gomorrah, written by St. Peter Damian in 1051. Sodom and Gomorrah. Sodom. Sodomy.”

Sister Kenny laid some of the blame for the denial, minimization, secrecy, marginalization of whistle blowers, and protection of offenders on church leaders’ misdirected priorities. Although the word scandal is associated with a loss of reputation, the Greek word scandalon actually refers to an obstacle. In the Bible, creating a scandal means putting an obstacle in someone’s way to God.

“Many of these victims were never able, are never able, and will never be able to turn to God. For whatever other reasons people lose faith, this trauma has spiritual abuse at its heart,” she said.

Sister Kenny said that church leaders deferred too much to experts in medicine when they allowed the priests to return to parishes after as little as six-month stays at “Houses of Affirmation.” This showed how out of step society was at the time when it came to sexual abuse—and it was hardly confined to Roman Catholic circles.

These offending priests became “what Phillip Jenkins has called an example of moral panic—that is, the offenses committed by priests became a moral scapegoat of sorts, so that if we focus on pedophile priests, then we don’t have to focus on the societal issues,” she said. “Of course, the reality is, it’s both in the church and in society that we need to deal with the issue.”

Lawsuits by lawyers brought the scandal to light, brought compensation for victims, focused on institutional failure, and spurred action from both law enforcement and from church officials, she said. On the other hand, there is now more fear of disclosure because of the threat of litigation, and there has been immeasurable damage to innocent priests’ reputations.

“Priests will tell me they will not wear their collar in places because if they wear their collar, they see people walking away,” she said. “These are the good guys, the men who are trying to be men of god.”

Defense lawyers deserve blame too, for promoting interpretations of the law that completely contradicted bishops’ pastoral responsibilities. She suggested lawyers examine how a 1917 Canon Law was updated in 1983 to make it harder to remove a priest from his post.

“The empirical research I know on the dynamics of sexual abuse and on the crisis as it unraveled in the West, identifies both individual risks and systemic and cultural beliefs and practices,” she said.

“It’s about the way we think and act about truth, obedience, silence, and sexuality. The way we think about these things all plays a part in abuse.”