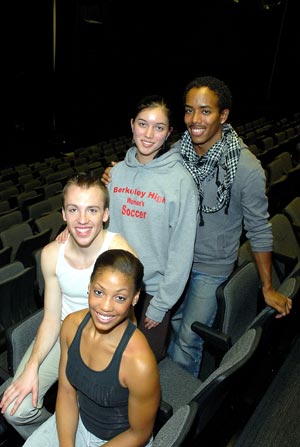

Photo by Ken Levinson

Daniel Harder wanted a college education and a dance education, and didn’t want to choose between the two. He felt the pull of the classroom and the conservatory at the same time.

It’s a choice many young dancers struggle with, according to Jordan McHenry, who also wanted to delve into academics while intensively practicing his art.

Both students found what they needed in a degree program offered jointly by Fordham College at Lincoln Center and the nearby Ailey School, official school of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Every week the students take dance courses at Ailey and college courses at Fordham, gaining a liberal arts education that infuses their dance work with extra creativity.

The joint bachelor of fine arts degree program marks its 10th anniversary this fall. Students said the program continues to evolve, helping them find new ways to meld their academic pursuits and intellectual growth with the world of dance.

Some have traveled the country, or the world, to perform professionally while completing their studies. They pursue academic specialties to broaden their options within the dance field. Several are taking advantage of a new choreography specialization, or undertaking projects that grew out of the program’s creative hothouse.

“The sky’s really the limit,” said Harder, a native of Bowie, Md., who is a senior in the BFA program.

With the help of Ailey, one student is arranging a cultural exchange in Mexico next summer for 15 students who will teach dance in orphanages. She said her Fordham coursework and its Jesuit values have helped her understand why and for what she dances.

“Having the academics really helps you reach further into yourself,” said the student, Joanna Poz-Molesky, a junior from Berkeley, Calif.

Technical skill isn’t enough to succeed in today’s dance world, the students said. Dancers need expressive ability as well. Some choreographers tell dancers to draw upon philosophy when interpreting dance movements. Harder said one of his Ailey instructors had students relate their dance moves to a painting by Caravaggio.

The BFA program has 77 students, according to program co-director Ana Marie Forsythe, an Ailey administrator. Students take 16 courses at Fordham, including core courses—history, religious studies, philosophy, literature and others—along with dance-related electives. They must complete 144 credits, compared to 124 for a typical Fordham undergraduate.

Ailey teaches numerous dance styles including ballet, jazz, West African and tap. Students study anatomy and kinesiology and learn how to build their careers and practice good nutrition.

In short, they

Photo by Ken Levinson

get conservatory-level training along with a serious liberal arts education, said Robert R. Grimes, S.J., dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center.

“Fordham and Ailey pioneered a new way to think about dance in higher education,” Father Grimes said. “Our BFA students take twice the number of liberal arts courses other programs require. The Ailey/Fordham graduate is a ‘smart’ dancer in every sense of that term.”

A literary passage gleaned from a class at Fordham lent inspiration to McHenry as he was choreographing a show at Ailey. The passage by Lebanese-born writer Kahlil Gibran described timelessness. It formed the concept for McHenry’s production, in which dancers portray the beauty of human diversity by performing unique dances, one by one, inside a spotlight that represents the final moment of life.

“It really was an exploration of how everyone lives their lives so differently” within the same mortal constraints, he said.

It was one of nine performances by students at The Ailey School on Oct. 30. They performed varied techniques to varied music such as gospel, rock, blues and rap. Seniors in the BFA program choreographed each piece—the lighting, the costumes, the music and the dance movement.

“It’s all from the ground up,” McHenry said.

Fordham already had a hand in the dance world at Lincoln Center before the program launched in 1998. Fordham students took electives at The Ailey School, and dancers with the New York City Ballet took courses at Fordham, said Edward Bristow, Ph.D., a Fordham professor of history who was dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center at the time.

“We were familiar with how interesting and rewarding it is to educate dancers,” he said. “They’re constantly being corrected in their studio work, and they’re looking to become better, which carries over into a more academic setting.”

Bristow co-founded the program with Denise Jefferson, director of The Ailey School, and serves as program co-director at Fordham.

Students must apply separately to Fordham and The Ailey School before undergoing a rigorous audition process. Last year, 350 dancers applied, 35 were accepted and 20 enrolled, Forsythe said.

Forsythe estimated that 60 to 65 percent of graduates have paying jobs as dancers, either in companies or on Broadway, within a year of graduation. Some graduates go on to dance professionally with both the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and Ailey II.

Photo by Ken Levinson

Time management is critical, the students said. They’re in class 35 to 40 hours a week and many work paying jobs to meet living expenses. “Dancers do eat,” Harder said jokingly.

Then there’s the additional coursework some of them pursue. One senior in the BFA program—Amy McClendon, of Jacksonville, Fla.—said she’s studying business administration so she’ll have other options, such as running her own dance company. The students know they can dance professionally for only so many years.

The program has adapted when students’ careers took off before they graduated, McHenry said. Two students recently landed “the job of a lifetime,” which took them to Chicago, but were able to continue their studies, he said.

Harder toured Europe from June to September, playing one of the Sharks in a production of West Side Story in London, Athens, Greece and Düsseldorf, Germany.

“It was amazing,” he said. “The training that I have received here over the past three and a half years definitely helped.”