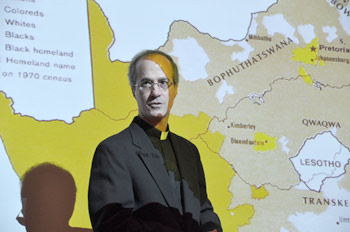

Photo by Janet Sassi

South Africa’s post-World War II apartheid policies were at odds with the beliefs and values of that nation’s Roman Catholics, but the church delayed calling for the elimination of the colour bar, a Jesuit scholar said on Dec. 1 at Fordham University.

R. Bentley Anderson, S.J., Fordham’s Loyola Professor of History, traced the church’s change of conscience regarding the segregated system, officially mandated in 1948, which oppressed the rights of blacks while maintaining white supremacy in government and society.

Working from the writings of a South African Catholic bishop—Denis Hurley, archbishop of Durban—Father Anderson said that the leader voiced a religious objection to the colour bar as early as 1951. Yet he did not publicly call for its removal.

At the time, Catholics made up 5 percent of the South African population, or 1.5 million people.

A product of his time, Archbishop Hurley accepted the notion that South African blacks were less developed socially, less educated, and in need of “uplifting.” Father Anderson said that this paternalistic, euro-centric attitude enabled the archbishop to overlook the legality and morality of laws that discriminated against blacks, including “pass laws” requiring black men to carry identification booklets or face arrest.

It wasn’t until 1953, Father Anderson said, that Catholics took a stronger stand against apartheid. In that year, the apartheid government passed the Bantu Education Act, which squarely put the job of regulating curricula for black South African students under state control, and out of the hands of faith-based mission schools. At the time, the church was educating more than 100,000 black students, or 15 percent of the national student population, teaching a theology that acknowledged the dignity due all persons regardless of race.

“The faith-based schools had become a threat to the apartheid regime in that [they]were raising the expectations of their black students,” Father Anderson said. “The apartheid government was never going to allow blacks to be assimilated or incorporated into white society as equals.”

Apartheid, the bishops of South Africa wrote in a 1957 missive, was “a system that was nothing more than the endorsement and advancement of white supremacy,” one in which “the white man makes himself the agent of God’s will and the interpreter of His providence in assigning the range and determining the bounds of non-white development.” In spite of such biting language, however, the bishops advocated “gradualism” and called for working patiently to resolve differences.

Finally, in 1959, Archbishop Hurley called publicly for the elimination of the colour bar within 10 years. At that time, the archbishop still believed that blacks were less developed socially, economically and educationally, but he now placed the blame for these differences on the apartheid system, writing that the “big obstacle to the single society is the colour prejudice of the white man” and not necessarily differences between races. He had concluded that, no matter what cultural or financial condition a black South African might have, he or she is still “not accepted as a member of the South African community.”

“For Hurley, that was an act of injustice,” said Father Anderson. “Dignity is the foundation of human existence. Human dignity is the cornerstone of human respect.”

Hurley concluded that if race-based prejudice was not removed from South African society, the oppressive racial policies would be overthrown by both its own people and by outside pressures.

“‘Eliminate the Colour Bar,’ Hurley argued, ‘or face revolution,’” said Father Anderson.

It took more than a decade for the Catholic Church to come to its realization about apartheid policies, but violations of human dignity, social justice and morality finally convinced the church to advocate for equality under the law, he said.

The archbishop lived to see that happen, Father Anderson added, in 1991—some 35 years after he spoke out.

“His was a journey of self-discovery and communal enlightenment,” said Father Anderson.