Fordham University has awarded Robert Miraldi’s book on investigative journalist Seymour Hersh the 2014 Ann M. Sperber Award.

Fordham University has awarded Robert Miraldi’s book on investigative journalist Seymour Hersh the 2014 Ann M. Sperber Award.

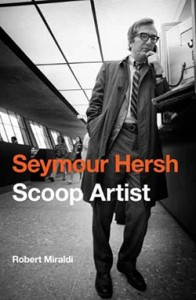

Miraldi will accept the honor at a ceremony at the Lincoln Center campus’ Corrigan Conference Center on Wed., Nov. 19 at 4 p.m., where he will give short talk on his book, Seymour Hersh: Scoop Artist (Potomac Books, 2013).

The Sperber prize, presented by the Department of Communication and Media Studies, is meant to encourage biographical works that focus on media professionals. It is given in honor of Ann M. Sperber, author of the biography of Edward R. Murrow, Murrow: His Life and Times, (Fordham University Press, 1999) and was established with a gift from Sperber’s mother, Lisette.

Miraldi, who holds a doctorate in American studies and a master’s in journalism, said that investigating one of America’s best investigative journalists required a combination of scholarly research and gumshoe reporting.

The 77-year-old Hersh’s career began in the early 1960s. Miraldi bookends the biography with Hersh’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1969 free-lance coverage of the My Lai Massacre and his 2004 reporting for The New Yorker on the U.S. military’s mistreatment of prisoners at Abu Ghraib.

Miraldi, a professor of journalism at the State University of New York’s College at new Paltz, said the research took about eight years. He said he called the legendary journalist to inform him of his plans to write the biography, to which Hersh replied, “I’m not dead you know.”

Miraldi said that as a scholar he “dug” into Hersh’s work, which includes nine books, dozens of New Yorker articles written from 2000 to 2010, hundreds of articles for the New York Times written from 1972 to 1979, and a trove of articles that Miraldi uncovered from the Associated Press archives written between 1962 and 1967. He also examined memos, letters, CIA documents, and FBI files.

Miraldi also contacted hundreds of Hersh’s colleagues, including the late great Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee, who told Miraldi that not hiring Hersh “was a helluva’ mistake that I’ll regret for the rest of my life.”

“One is intimidated by investigating one of the greatest investigative journalists, so I’d say that I approached it more as a historian than as a reporter,” Miraldi said. He added that a historian would interview a source and ask “Do they have papers?” to back up a claim, whereas a reporter would ask “Do they have a telephone?”

For his part Hersh was accommodating, if not fully accessible, since he’s at work on a book about former Vice President Dick Cheney. Miraldi said the journalist gave the project a “semi-blessing” and was helpful, but drew the line at access to his family. Nevertheless, the two exchanged plenty of emails and held several phone conversations.

Miraldi said that Hersh was part of movement in journalism that was fed up with “the rule of objectivity,” in light of the horrors of war. With journalism today in a state of profound flux, Miraldi said that he still holds out hope that new generations of journalists will carry on long-form investigative pieces that challenge authority.

“It begs the question as to whether will we see investigative journalism in an age of quick hits, but on the other hand the long form really can flourish in new media,” said Miraldi.