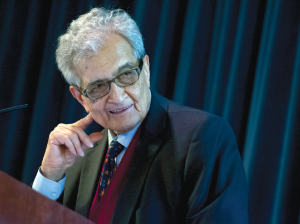

Amartya Sen, Ph.D., the Nobel Prize-winning economist and Harvard professor, arrived at Fordham’s Rose Hill campus after students had begun to leave for Easter break.

Even so, his April 16 lecture at the Walsh Library saw dozens sitting on the floor and dozens more standing in the back of the Flom Auditorium.

Sen is an economist, but his appearance attracted students of philosophy, music, and business, as well as students from other area colleges. His work on poverty, gender inequality, Indian history, and philosophy all played a role in his talk, “Why Do We Tolerate Poverty in a Rich World?”

Sen said he first encountered poverty as a child when the Bengal Famine of 1943 filled the region’s streets with the starving. Of the many horrors he witnessed, none struck him more than when he gave a banana to an “extremely emaciated woman with a severely skinny child on her lap.” The woman instinctively put the banana in her mouth before spitting it out, bursting into a piercing cry, and then giving the banana to her child.

“We’re no longer human beings,” she told Sen. “Our instincts are worse than animals.”

Sen said the instinctual inhumanity on the part of the starving is mirrored by an inhumanity within middle and upper classes capable of ignoring the situation.

“How do so many secure people come to terms with the gruesomeness surrounding them?” he asked.

He said that ignorance certainly helps alleviate responsibility for some. But there are others who believe that humans are “basically self-centered creatures” and that those hoping for change are “hopelessly romantic.”

Those who accept the “hypothesis of intractability” should be reminded that massive-scale poverty was brought under control in Europe, Asia, the United States, and more recently in Latin America, he said.

Even though India’s average income today is about five times what it was under the British Raj, the poverty is far more intense, he said. Despite the fact that 300 million people make up a thriving middle class, the country still lags in providing education and healthcare to its citizens.

“There is very little understating how out-of-line India is compared to other developing nations,” he said.

Many blame the country’s ancient caste system, he said. (When a caste system in the Indian state of Kerala was upended after protests spurred changes, the state developed some of the best benefits in education and healthcare in the country.)

But such a conclusion would be inadequate, he said, as the impact of the traditional caste system is “contingent on the nature of the politics of development.”

The caste system, however, has muddied the focus of public reasoning, he said—for which he laid a lion’s share of the blame on the mainstream national media.

“The silence of the media on the persistence of deprivation has been deafening,” he said. “It has played a gigantic role in keeping India grossly uninformed.”

He said that with India being the world’s largest democracy, media coverage of the problem is key to solving the problem. But coverage has been “distorted” as newspapers grumble about handouts and include angry reproaches on “fiscal irresponsibility.” Sen’s own economic analysis concludes that more subsidies go toward the rich than to the poor.

“As media denounces subsidies to the poor, the country has missed out on the lessons of the so-called Asian experiences,” he said. “India is falling behind in living conditions even as it overtakes its competition in growth.”

He noted that Japan and South Korea made skillful use of advancements in education and healthcare to bring economic growth to their countries. And China can address issues like healthcare with breathtaking speed using a totalitarian approach, he said. As a democracy, India can and should make the case for change to its millions of voters.

“There is nothing authoritarian about providing healthcare, and it’s the practice of democracy that will allow us to analyze it,” he said. “India is a democracy. When the problems are harder to understand, they need to be focused on by the media, and that’s critical.”