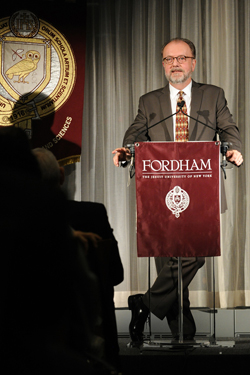

Photos by Chris Taggart

About midway through delivering Fordham’s fall Gannon Lecture in the United Nations Delegates Dining Room on Nov. 15, author and humanitarian Hugh Locke paused to collect himself.

Overcome with emotion, Locke, whose non-governmental organization (NGO) is on the ground in Haiti, was overcome with emotion expressing his “personal feelings on the U.N. peacekeeping mission’s responsibility for introducing cholera” in an already ravaged Haiti.

“The only people who don’t believe that it was inadvertently introduced to Haiti by U.N. peacekeeping forces are the lawyers in this building,” he said. “They are doing a terrible disservice, because how can you occupy the moral high ground when you [don’t] take your own principles to guide your actions?”

In an otherwise soft-spoken and even delivery, Locke also made clear his affection for the organization, noting that the first time he was ever in the Delegates Dining Room was as a teenager—when he won a trip to the U.N. for an essay he wrote.

Locke’s lecture, “Haiti: Post-Disaster Reconstruction, Sustainability, and Development,” was geared toward a potential future for Haiti, and for those NGOs and U.N. agencies doing humanitarian work. He said that many NGOs’ manners of operating have contributed to problems in Haiti and other developing countries because they foster a culture of dependency rather than working alongside the poor.

“Collectively we feel like we are anointed by the Divine to transfer money to the rich and give it to the poor,” he said of NGOs.

Locke’s own NGO launch was begun with a grant from Timberland footware and apparel company. At the insistence of Timberland’s chief Jeff Schwartz, funding was contingent upon the support program becoming self-reliant. It had to function on its own after Locke was no longer involved. The result was the Haitian-based Smallholder Farmers Alliance, which assisted in motivating small farmers to plant trees.

Locke said that part of the cycle of devastation that Haiti experiences nearly every year comes through deforestation. Once known as the “Pearl of the Antilles,” Haiti went from 60 percent tree coverage in 1915 to 2 percent today. The reason is because Haiti’s primary fuel source is charcoal and wood; nearly 30 million trees are consumed a year. Without vegetation, mountainsides act like funnels, sending the rain into the valleys and causing soil erosion and crop loss.

To address the problem, Locke said, the United States sent nearly 400 million trees that were essentially dropped at Haitian farmers’ doorsteps with the request that they volunteer to plant them. But without a real economic incentive, there was little likelihood that the farmers would do so.

He also detailed a 50-year history that encouraged the dissolution of small-scale farming in Haiti in favor of importing food from U.S. industrial farms. Today Haiti is the fourth largest importer of U.S. rice, even though half of the country’s work force makes a living farming.

In the hope of attracting volunteer tree planters, Locke and his partners began to offer agriculture services in exchange for tree planting. What started with 200 volunteer farmers has grown to 2,000 farmers who have planted nearly 3 million trees over a 40-square-mile area.

Initially, the exchange included seeds for the farmers, but once again Locke had to step back and let the farmers take control. Now the farmers have to buy the seed, negotiate the price, and come back to the community to get approval for the purchase.

“Once you take the first layer of oppression off of a community, you then create the circumstances for that community to begin to function for the better,” he said.

“You have to plan your exit strategy from day one,” he said.