On a humid night in July, students crammed into a small fifth-floor classroom at Fordham College at Lincoln Center to hear a talk delivered by Herbert S. Chase, M.D., professor of clinical medicine in the Biomedical Informatics Department of Columbia University and resident scholar at Fordham’s Center for Digital Transformation.

On a humid night in July, students crammed into a small fifth-floor classroom at Fordham College at Lincoln Center to hear a talk delivered by Herbert S. Chase, M.D., professor of clinical medicine in the Biomedical Informatics Department of Columbia University and resident scholar at Fordham’s Center for Digital Transformation.

Though the lecture was part of a Graduate School of Business Administration (GBA) course on big data, professors from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) joined students from the Graduate School of Social Service (GSS).

“That’s what struck me,” said Dr. Chase. “In that room there were these people with such diverse interests.”

Even as scholars debate the very definition of big data, most agree that big data will encompass almost every discipline and that coordination will be key to harnessing its power. For his part, Dr. Chase defines big data as “a humanly incomprehensible amount of information that only a machine with sophisticated algorithms can understand.”

Dr. Chase is not a computer scientist; he is a kidney specialist. His role is essentially that of translator between medical specialists and computer scientists. For big data to produce results, he said, the two disciplines must work in tandem.

“It’s the classic team effort: the computer scientists need to tell the researchers what’s possible, and the experts know the questions,” said Dr. Chase. “And that’s what is happening in every discipline. There’s the content expert and the computer expert.”

For many in computer science, big data is just a new term for an old concept.

“Big Data has been there for a long time, but the phrase has become popular because of the explosion in data collection,” said Frank Hsu, Ph.D., the Clavius Distinguished Professor of Science and professor of computer and information science. “It has been branded by the business sectors, just like the Internet. The Internet has been around since the 1970s, but in the 1990s when the WWW was introduced, everyone said, ‘Oh this is so useful! The Internet!’”

Gary Weiss, Ph.D., an associate professor of computer and information science, traced the etymology of the term to “data mining,” which he said has been popular for the past 10 to 15 years. It was preceded by “machine learning.”

“The other term that is becoming very popular is ‘data science,’” said Weiss, who joins Hsu and other Arts and Sciences faculty to teach Fordham courses on data mining, bioinformatics, and information fusion.

But the question as to what constitutes “big” is nearly as subjective as the definition of big data. Does big data require billions of records? Weiss said that in theory a classic case would be a multinational corporation like Wal-Mart analyzing sales records that include billions of transactions for millions of people. But it could also be argued that big data includes relatively modest health study focusing on a couple hundred people.

For example, through Fordham’s Wireless Sensor Data Mining Lab, Weiss has developed a mobile healthcare application called Actitracker. The app collects large amounts of data about the users’ activity via an accelerometer embedded in their smartphone. Weiss said such “mobile health” applications (yet another fresh tech term to add to the digital lexicon) represent a huge growth area for big data.

“From a single subject we’re collecting data every 50 milliseconds, which is 20 times per second, so you can see how that can add up over 10 hours,” said Weiss—especially when multiplied over the apps’ 147 current users.

The Actitracker system reports 2,535 hours of data. That’s 182.5 million records, or data points, gathered from 147 people. Just one user using the app for 12 hours a day for 30 days generates 26 million records, or 104 million pieces of information.

“Sure there’s the health data, but people are applying these techniques to any kind of data,” he said. “It certainly relates to business. In astronomy a telescope is going to generate terabytes of data. Then there’s the digital humanities.”

Fordham’s Center for Digital Transformation

“Big data was just lazy data that was just sitting there, but now that we

have the technology to analyze the data, all sorts of issues are emerging,

such as the privacy issues, security issues, as well as governance and

the ownership.”

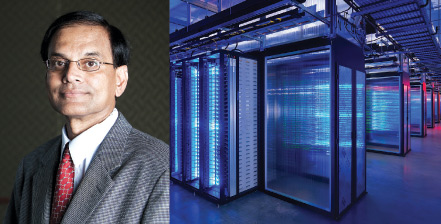

Though his courses are situated squarely in GBA, “R.P.” Raghupathi, Ph.D., director of GBA’s Business Analytics program and Fordham’s Center for Digital Transformation, spent time discussing under-tapped areas of big data in the humanities, such as video, music, text, and audio.

In addition to the course in big data analytics, GBA has developed a host of programming to address market needs, including master’s programs in business analytics and marketing intelligence. All analytics courses are full this semester. A new program in applied statistics and decision-making is awaiting state approval.

Though Raghupathi is enthusiastic about preparing students for big data’s potential, he does have concerns.

“Big data was just lazy data that was just sitting there, but now that we have the technology to analyze the data, all sorts of issues are emerging, such as the privacy issues, security issues, as well as governance and the ownership,” he said. “Who owns this data?”

Raghupathi said that ethics and related issues, such as privacy concerns, are woven into every course at GBA.

Joel Reidenberg, Ph.D., the Stanley D. and Nikki Waxberg Chair of Law, is doing some revealing big data research on the question of ownership and privacy.

Reidenberg directs Fordham Law’s Center on Law and Information Policy (CLIP), which has zeroed in on the use of personal information gathered within big data.

“Big data is a catchphrase that is poorly understood by the general public, and most of it is taking place behind the scenes,” he said. “It involves the large-scale collection of personal information that can be used for predictive modeling of behavior, planning, detection, and surveillance.”

Reidenberg’s recent research through CLIP has centered on education and children’s privacy. As the federal government has encouraged or forced states to set up databases reporting children’s progress, detailed information—ranging from a child’s weight to a bad report for cursing—could become a permanent part of a child’s records.

CLIP is looking into how public schools are outsourcing storage of student information to the digital cloud, which could contain everything from a student’s seventh-grade PowerPoint presentation to his 12th-grade SAT scores.

Entire cities are contracting with data analytic companies that can, in turn, sell municipal information to yet another party, he said. The companies’ business models sometimes include little or no charge for services because they make up their costs by data mining and then reselling information.

Reidenberg said it is quite clear that school districts have difficulty understanding what they’re doing, let alone being able to protect a student’s privacy.

“Does the data get deleted or archived when the kid leaves the school, or does the kid’s seventh-grade blog post pop up when he or she applies for college or a job?” said Reidenberg. “That detailed personal data is part of what’s being crunched in big data and there are questions on the ethicacy of collecting that.”

Raghupathi noted that privacy concerns about identifying patterns in big data were further exacerbated after the National Security Administration mined phone records data. The NSA’s antiterrorism strategy certainly raised public awareness about data mining, but not in a good way, said Raghupathi. He expressed concern that the fallout from controversies could overshadow progress.

“The technology is there for us to use it for good purposes,” he said. “It is very important to resolve these legal and social policy issues before the public perception about big data gets distorted.”